I still remember how I felt while reading the letters for the first time.

“Why should the taxpayers finance a festival designed to promote and strengthen homosexual community which in a large measure is instrumental in the spread of the AIDS epidemic, a serious health threat to all and an added cost to taxpayers?”

“The government is short on cash and talks about restraint when it comes to meaningful programs but thinks nothing of supporting gay-erotica.”

“We feel that by giving this money to the Gay festival you are publicly endorsing their activities which we do not agree with, as homosexuality is morally wrong.”

Eight such oppositional letters made their way to Manitoba’s Ministry of Culture, Heritage, and Recreation in 1987 after an article about Canada’s first annual queer film festival, Counterparts, was published in the Winnipeg Free Press.

At first I laughed at these letters, their absurd leaps in logic a relic of a distant, homophobic past. But as I read more, I could feel my chest tighten. I started to feel like the letters were directed at me – a dose of crushing homophobia in a single afternoon.

In all the acrimonious letters the provincial government received that year, the greatest source of moral outrage was over public funding of the queer film festival. Undeterred by these letters and the mounting opposition, the government stood firm and funded the festival anyway.

These days, it might be unusual for a government to receive and act on such letters – not because homophobia is a thing of the past, but, more critically, because most queer organizations do not rely solely on public funding anymore. Gradually, banks and large corporations have begun to fill this void, but, as Cinema Politica co-founder Ezra Winton notes, queer and other activist festivals have had to “make compromises in order to receive funding.” Coupled with the development of a new homonormative culture – what Lisa Duggan calls “a privatized, depoliticized gay culture anchored in domesticity and consumption” – funding queer festivals has become useful to large corporations: they earn progressive credentials while pinkwashing capitalist exploitation of queer folks, especially queer people of colour. Queer activists in large cities have been rightly critical of this state of affairs, drawing attention to the corporatization of pride, but the conversation has been relatively muted on the Prairies.

Though corporate sponsorship of queer festivals may seem like both a road to, and evidence of, the success of queer social movements, it clouds the fact that capitalism ruthlessly stratifies our society along lines of gender, sexuality, class, and race. If our queer festivals aren’t intersectional, anti-capitalist, anti-colonial, and anti-racist, then who are they for?

This isn’t to say that governments and public funders don’t constrain radical politics and creativity. Funding applications and reporting mechanisms entrench certain assumptions about what is worthy of funding. The difference, however, is that there are far fewer avenues to pursue accountability in private or corporate spheres than with public funders.

Almost all queer film festivals (QFFs) have struggled with this particular balancing act, but the QFFs on the Prairies in particular are an interesting site for examining the influence of capital. Unlike in major urban centres with robust independent film cultures and large queer communities, queer films were seldom, if ever, screened at the local cinemas of small Prairie cities before the early 1970s. Faced with the costs of shipping films to their communities, queer activists had to be creative if they wanted to bring in films and videos from across Canada and the world.

Screenings throughout the 1970s and 1980s reproduced many of the same cissexist, colonial, and racist features of mainstream film exhibition, showing films primarily by and about white gay men and replicating problematic tropes. However, in many cases, these early screenings were still the first time gay men, and sometimes lesbians, on the Prairies saw themselves represented on screen. Along with bars and social clubs, film theatres were important to the growth of queer movements.

At the height of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, queer films and videos became critical pedagogical and advocacy tools, normalizing safer sex in often funny and explicit ways. In the early 1990s, New Queer Cinema (NQC), pushing back against the stigma of AIDS, brought the radical politics of queer experimental filmmaking to mainstream film festivals. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, though, the effects of NQC had softened, and Will & Grace defined the syrupy new iteration of mainstream queer representation. With palatable narratives on hand, private television broadcasters, film distributors, and big banks all wanted a piece of the big pink market, and they began to funnel their money into major QFF sponsorships.

It’s not the size of your budget, but how you use it

It is difficult to say exactly how much corporate sponsorship factors into queer festivals’ budgets. As non-profit organizations, most film festivals are under no obligation to disclose these figures to anyone but their members or boards of directors. The only definitive statements are those in the archives.

The early financial records of the inaugural Counterparts festival reveal that the largest funder in 1987 was the government, along with some donations from gay organizations and gay-friendly businesses. For the most part, organizers had no difficulties accessing this funding.

Problems only arose when Counterparts asked for funding more than once. The government stated that it had money only for “a limited number of extremely large and high-cost arts festivals.”

Counterparts continued to struggle with funding throughout the 1990s and held festivals only sporadically throughout the decade. When it returned in 2000, renamed Reel Pride, it was bankrolled by the television network Showcase and other private sponsors; by 2011, the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) had been named presenting sponsor.

The moral outrage directed at Counterparts in its first year was repeated across the Prairies; homophobic critics used the sanctity of public capital as a cover for their objections to queer art. In 1995, a conservative radio talk show host read on air the titles of videos at Calgary’s first QFF, The Fire I’ve Become. Conservative listeners leapt at the opportunity to call in with insinuations that Thirza Jean Cuthand’s Lessons in Baby Dyke Theory (1995) was literally about infants, despite the activist collective of queers of colour organizing the festival, Of Colour, clarifying that it was actually “about newly-out [sic] lesbians.” The public nature of the festival’s funding and venue – the Glenbow Museum – only made conservatives clutch their pearls tighter.

Glenbow was inundated with 150 phone calls from enraged listeners. Glenbow officials buckled under the pressure and moved to cancel the event. Of Colour quickly organized a public meeting, drawing representatives from 21 organizations. Over two hours, they acquainted Glenbow officials with the history of queer culture and censorship. The Glenbow, for its part, requested that organizers submit their films to the Alberta Film Classification board, but ultimately the festival continued. Despite all of the panic, sensationalism, phone calls, and threats to call in the police, only two protesters showed up at a meagre rally against The Fire I’ve Become. The festival was a success.

No sex, please, we’re a non-profit

But the following year would turn out to be the final year for The Fire I’ve Become. And for the next two years in Calgary, no other QFF got off the ground.

In 1999, the Calgary Society of Independent Filmmakers (CSIF) and the Gay and Lesbian Community Services Association organized Fairy Tales. Remembering the sting of controversy surrounding The Fire I’ve Become, activists approached Fairy Tales cautiously, intentionally depoliticizing the festival.

“We want to make it clear that this festival is not a political forum,” organizers at CSIF wrote in an unsigned memo in 1999. “The CSIF exists as a non-profit organization, and as such, we’re obligated to avoid promoting any kind of political motives or objectives.”

Corporations do not openly control programming, but many organizers are attuned to the kind of homonormative and neoliberal diversity politics large corporations tend to support. Both Fairy Tales and Reel Pride have diminished the number of short experimental films, and screen almost exclusively homonormative, Hollywood-style narrative films. Combined with the global trend toward a more institutionalized queer film market, the possibilities for queer festivals to be sites of radical left politics, and to become anything more than sites of homonormative consumption, diminishes.

Shhh, no porn in the library

Regina’s Queer City Cinema has in some ways bucked this trend since its inception in 1996. Though it hasn’t been able to avoid large corporate sponsorships entirely, it has maintained its radical politics. In 2000, Gary Varro, Queer City Cinema’s executive and artistic director, screened pornography and other sexually charged films and videos alongside videos about marriage, family, and community.

“It was meant to be this juxtaposition of something warm and cozy and fuzzy and something terrifying, uncomfortable, and titillating at the same time,” says Varro. “I never thought it was going to produce the controversy it did.”

A predictable chorus of opposition sounded off in Regina, just as it had in Winnipeg and Calgary. The festival’s public funding – which came from the city, Canada Council for the Arts, the Saskatchewan Arts Board, and a handful of Crown corporations – became the cause célèbre for conservatives.

“Why would you have people there actively talking about pornography in a library beside children?” asked conservative Saskatchewan Party MLA June Draude in the Saskatoon StarPhoenix, referring to the fact that the venue was located next to a children’s library. “It’s a black-and-white issue. We have taxpayers’ dollars and pornography used in the same sentence. No.”

Though Draude had hoped that public funding agencies would turn away future funding applications from Queer City Cinema, the conservatives’ panic unwittingly drew in bigger audiences.

Though in 2012, Queer City Cinema expanded to include a separate performance art festival, municipal funding was slashed from $20,000 in 2013 to $6,000 in 2014. Varro turned to TD Canada Trust in 2013 to help fill the funding gap, but the bank’s support remains dwarfed by the festival’s 10 public sponsors.

When government funding is inconsistent, QFFs turn to corporate sponsors. While they escape the trap of inadequate funding, they enter a new one: the unpredictable interests that determine if a corporation is squeamish about queer sex. Fearful of the bad press brought on by moral panic, QFFs may play it safe to avoid scaring off skittish corporate funders. The neoliberal imperative requires festivals to demonstrate growth year over year, but without audiences, there is no growth, and without growth, there is no funding. But by playing it safe, they also run the risk of disappointing their audiences.

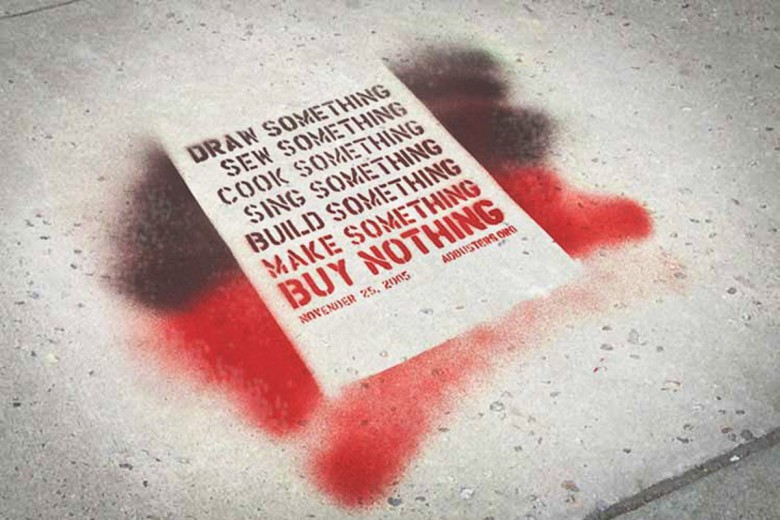

Queer festivals can flourish – and have – without centring corporate sponsors and without kowtowing to conservative moralists. I spoke with Varro the day after Donald Trump was elected.

“Today’s one of those days where I would just like to say I really want to ruffle some feathers. I really want to stir it up. I really want to piss some people off. I’m not going away with this festival. It’s staying here. And it’s going to be in your face,” said Varro.

Saskatchewan is a hotbed for this type of determination. With Varro curating performance art alongside film screenings in 2016, along with bringing filmmaker John Waters – well known for his transgressive and politically volatile films – to Regina in June 2017, we just might see a reinvigoration of the QFF scene on the Prairies and elsewhere.

In Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, Pitos Waskochepayis, a one-day two-spirited film and media arts festival organized by the Indigenous Peoples’ Artist Collective and curated by Varro, has occurred every year for the last five years without a single corporate sponsor.

When festivals strike a balance between growing and making radical political statements, the queer movement can build, maybe even in a global arts environment that is increasingly dominated by liberal and corporate interests. It’s not the size of the festival that matters, but the kind of political and cultural change it effects.

The author wishes to acknowledge that this research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the T. Glendenning Hamilton Research Grant from the University of Manitoba.