Sitting across the table from one another after dinner in Saskatoon, on the first night of our adventure to Batoche last fall, we were determined to find some karaoke. Our server racked her brain for good spots and suggested we try the Colonial. We shared smirks, and tested the waters: “Is there anywhere else?” “No, I think the Colonial is your best bet,” she said. “For sure, the Colonial,” we replied. A few stifled giggles and off we went.

In March 2021, the Red River Echoes (RRE) collective formed quickly and completely online, thanks to the pandemic and a revived Facebook chat. Most of us had never met in person but we shared common threads: we were Métis in or from Manitoba; we were increasingly frustrated by the Manitoba Métis Federation (MMF), an organization that calls itself our government; and we felt it was necessary to present another, explicitly anti-colonial, voice and vision.

What sparked the Facebook group chat was that, earlier that month, the MMF had taken out a full-page ad in one of Manitoba’s biggest newspapers commending the work of Winnipeg police chief Danny Smyth and showing support for the Winnipeg Police Service (WPS). “While it is known that some officers make decisions that can result in harm, we cannot let the actions of a few determine our confidence in the many,” the ad said. It’s unclear which of the countless harms the MMF was referring to – perhaps they were talking about the year prior, when WPS officers killed three Indigenous people in 10 days, one of whom was a 16-year-old girl named Eishia Hudson. The MMF claimed that their message was “on behalf of the Métis Nation.”

We were Métis in or from Manitoba; we were increasingly frustrated by the Manitoba Métis Federation (MMF), an organization that calls itself our government; and we felt it was necessary to present another, explicitly anti-colonial, voice and vision.

It was just the latest addition to a growing list of actions and statements by the MMF that we felt went against what it meant to be Métis. In 2020 alone, the MMF publicly denounced the Wet’suwet’en solidarity protests; dismissed calls to change the names of streets and schools named after the British military general who suppressed the Red River Resistance; and lobbied to evict houseless people who were living in an encampment outside the MMF’s Winnipeg headquarters.

In response, we set up a website and wrote our first open letter, in which we said: “These actions from the MMF go directly against what we Métis see as our responsibility to each other, to other Indigenous people and to our communities.” We asked the MMF to “act with honesty and humility when its members ask MMF leaders to fight for justice, instead of supporting those who hurt us.”

Our letter was met with an outpouring of solidarity, of grief and pain, and of celebration from Métis people across our Homeland. Our sudden presence embodied something that many Métis had been waiting for. One well-respected Michif Elder in Winnipeg told us, “I’ve been praying for you [to come into existence] for many years.” We felt that we had a responsibility to our People, to ourselves, and to our ancestors to speak up.

We began meeting online – as the youths do – and formed a team we’re sure our ancestors only dreamed of. Looking at one another in those Zoom grids, we found a group of mostly women, Two-Spirit, and queer folks. But what held us then and keeps us together now is not the righteous outrage that sparked our first open letter, but rather our desire to embody Métis ways of being: to practise reciprocity, good governance, and that noble mischief that runs in our veins. We didn’t want to theorize or talk about it – we wanted to live it.

Members of Red River Echoes sorting porcupine quills together in fall 2021. Photo courtesy of Claire Johnston.

Otipemisiwak

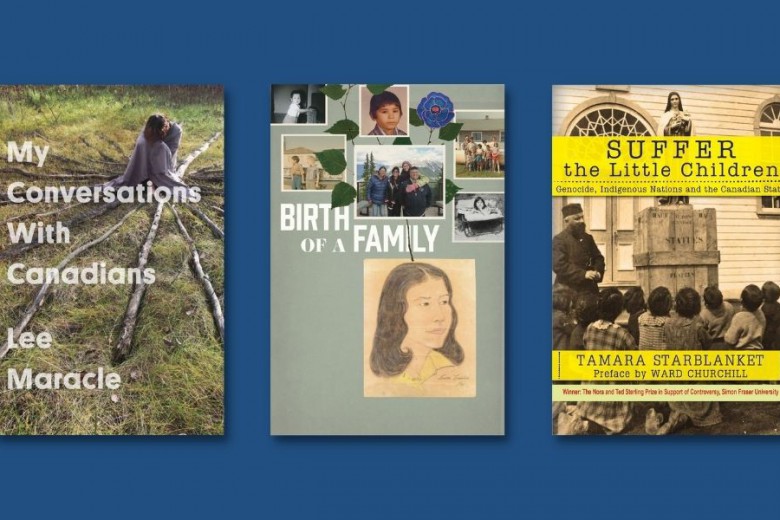

None of us imagined then – while we frantically typed our words into a Google Doc and collaboratively created a logo, a website, and a social media presence – the importance of this collective in our lives more than one year later. Since spring 2021, we have shared our work and words with thousands. We raised legal funds to protect those in Winnipeg who tore down colonial statues on July 1. We organized a community event to call for renaming a neighbourhood whose namesake came to Manitoba to brutalize the Métis. We stood alongside the family of Eishia Hudson to demand justice from the police force that killed her. We co-published a zine with the Mamawi Project – another Métis collective – and presented it at the first ever Métis studies symposium. We ventured across our Homeland to spend time with Métis author and matriarch Maria Campbell at her home in Saskatoon. We visited the graves of our ancestors and the land at Batoche. We learned to carve snow sculptures at the Festival du Voyageur and have started to traditionally tan hides together. We taught one another to bead, to lead meetings, to harvest and separate porcupine quills just so, to understand each other and share our different experiences as contemporary Métis.

One well-respected Michif Elder in Winnipeg told us, “I’ve been praying for you [to come into existence] for many years.”

Historically, the Métis were known as the People Who Own Themselves, Otipemisiwak. As our ancestors fought for their Nation, and against colonial expansion in allyship with other Indigenous Peoples, they governed themselves in their own ways. Drawing on this precedent of Métis governance, we wanted to think carefully about how to organize as a collective. The governance model we created allows for each person to contribute and use our gifts in ways that honour our time, capacity, and growth. We have five circles, or subgroups, responsible for different parts of the work we undertake – voice, relations, healing, governance, and education. Inspired by our ancestors and many others before us, we practise rotational leadership, which means that each collective member takes on a different responsibility – whether as a captain for a circle or the lead on a small project – for a period of time that depends on the member’s capacity, gifts, and often nomination by other collective members, before passing it off to another member.

As we considered the way these circles would work together, the image of a five-petaled flower formed. At a recent meeting with some other Indigenous organizers in Winnipeg, one Cree person joked, “you Métis will make anything into a flower.” We all laughed. It is a profound joy to us that the Métis were also historically called the Flower Beadwork People – this name will always connect us to the craft, to creativity, and to the land.

Each Thursday we meet in person or online, our weekly opportunity to show up to practise reciprocity. We bead, cook, drink tea, ask for help, laugh, cry, give help. We learn and unlearn. First and foremost – even before our public-facing advocacy work – we are committed to taking care of one another. These gatherings allow us to form the relations we know are the source of living mino-pimatisiwin, the good life. The connections between us as individual collective members; between Métis and First Nations; between us and Mother Earth and our winged, four-legged, and finned animal kin – these are all relationships we are invested in and devoted to exploring. It was a gift to find that we didn’t have to make a decision about these priorities; they became self-evident through our work together.

Red River Echoes’ governance model is arranged in a flower, with each circle representing different parts of the work they undertake.

Healing our relations

As mostly women, Two-Spirit, and queer Indigenous people on Turtle Island, we know that we and our families have faced, and still face, many layers of oppression. We come together as a group with varied experiences of class and privilege, including proximity to whiteness, and of shame and pride in our identities. We try to give one another the grace, space, and love to work through those things.

Some of that shame and pride has been passed down to us through many generations, so it’s only natural that the kin-making in our collective has, in turn, created ripples in our families and communities. In our group chat, members often share stories of RRE’s impacts on their families.

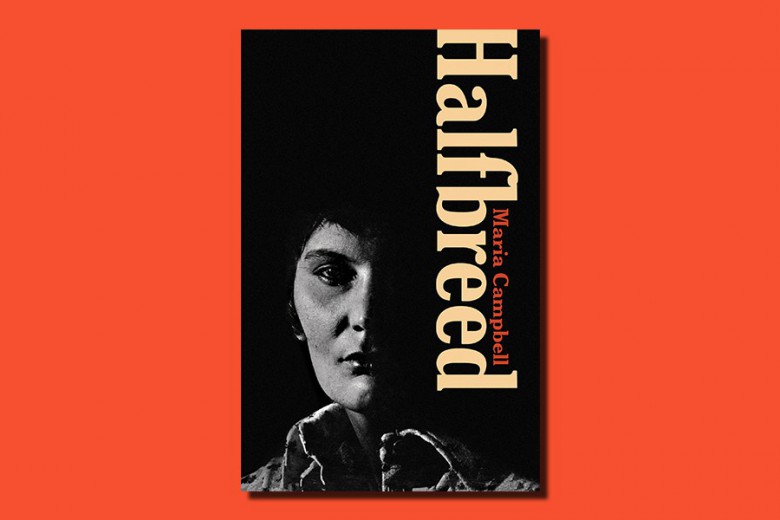

After we visited Maria Campbell, Sherise recalls sharing Campbell’s famous memoir with her grandmother: “I read my Nanan Halfbreed. We are gifting our families even with these stories and experiences.”

"I’ve been given the space to dream and imagine different futures for myself and my family.”

“I went and visited my auntie Verna and my Nanan today and I was just wishing you all could have all been there to meet them,” Sherise continues. “I’m sure one day you will. It was so awesome, and I don’t think I would have made such a point of going to see them if it hadn’t been for our trip and Maria talking about the importance of visiting.”

After a hide tanning workshop, Allie writes, “Called my Papa to talk about the hide tanning. It was really nice to share with him and hear about how his aunty used to process hides <3 I wouldn’t have gotten to have that conversation without y’all. Chii miigwech family <3”

Another member, who chose to stay anonymous, shares how RRE helped her explore art and sexuality: “Being in Red River Echoes has given me the space and support to pursue my love for material art – something that I previously didn’t feel I deserved to do. The insatiable love and need to make things runs so deep in my family. Because of the support and acknowledgment of my gifts in the collective, I’ve been able to find ways to honour my gifts and encourage my family members to do the same – something that wouldn’t have otherwise been possible. I’ve also felt deserving to be able to explore and understand my identity as a bisexual person. I’ve been given the space to dream and imagine different futures for myself and my family.”

Andrée Forest carving her first snow sculpture, of a giant squirrel, as part of Festival du Voyageur with the RRE collective. Photo courtesy of Natalie Baird.

By drawing strength from inside our circle, we’re working to rectify historic and present-day wrongs. One of the worst injustices that Métis people faced was Canada’s scrip system. In the late 1800s, the Canadian government sought to extinguish Métis title to land in Manitoba and modern-day Alberta and Saskatchewan, in order to open the West up for white settlement and commerce. The government distributed certificates for land or money – called scrip – to Métis people in exchange for their land rights. But the government made land scrip extremely difficult to redeem, forcing some Métis families to move hundreds of kilometres away from their homes. If Métis people cashed in their scrip, they were often cheated out of its value by land speculators; if they hung on to their scrip, they saw it dramatically devalued over time.

Scrip and displacement fractured our communities and families in an attempt to disarm us economically, physically, politically, and spiritually as a People. The Indian Act – which did not recognize Métis – added further divisions between First Nations and Métis. It disrupted the system of shared communities and land that existed between us – a system that differed from Western colonial concepts of private property and Crown land. Through residential and day schools, churches and governments forbade us from speaking Indigenous languages like Michif and Bungi (Bungee), severing us from our history and our ways of being.

Our ancestors died for a liberated future for their children. We fail to honour them if we do not continue the fight to exist on our own lands on our own terms.

These events are part of our history as a Nation, and we still feel their repercussions: the disconnection from land and culture that some Métis people face can be traced back to Canada’s attempted genocide. By sharing space together as Métis, we are rebuilding our kinship structures, discovering family ties and cousins along the way, and finding our way back to the land and ceremony. We are making our Nation stronger. As we wrote in our second open letter to the MMF, “We are not a threat to the Métis Nation, we are its hope.”

It does not sit well with us, watching Métis leaders further enmesh our Nation with colonial governments, corporations, and police. We are not interested in Indigenous governments that mimic colonial ones. If we are not dreaming and building futures beyond colonial realities, we are turning our backs on our ancestors who made a name for us as People Who Own Themselves. During the 1885 Northwest Resistance, our People fought alongside First Nations allies in order to protect our lands and ways of life from Canada’s colonial expansion. Our ancestors died for a liberated future for their children. We fail to honour them if we do not continue the fight to exist on our own lands on our own terms. This fight is one based on relations with other Indigenous Nations and in shared land back. Emily Riddle’s essay, “mâmawiwikowin” from Briarpatch’s Land Back issue sets out this vision beautifully.

Last autumn, our collective took a road trip to visit the last site of armed Métis resistance at Batoche. We stopped at a gas station on the way, our vehicles covered in brightly coloured window marker: drawn flowers and LAND BACK and RED RIVER ECHOES. We made do with the parking lot, laid out blankets, and had a big picnic on crushed gravel. We laughed loudly, eating in the sun, bellies full, sending love to our road allowance ancestors, who surely perched just as we did in centuries past. We continue on our journey to make them proud: to disobey the rules that have no place on our Homelands, to mend the disrupted circles of kin, and to find strength in our voices, hearing those joyful reverberations across time and space.

32 Echoes

by Andrée Forest

Last year, in spring, we sprouted fast, purposefully, a new voice, a voice. Here we are. He told us to go to hell.

In summer we walked amid the sea of orange and witnessed statues fall. Their thuds were flat, they had no roots.

In autumn we visited Maria, weaving across the Homeland, picking sage along the highway. Finding our family names in the leaves.

In winter we beaded and laughed and built in snow: we are here, our joy is real. The cold reminded us of each other, of rest, how to take care.

Spring came ’round again, melting pelts, the solstice celebrated our birthday. Hide and smoke in our hair, three sisters shared their bounty.

Yet when she stood, thousands of eyes on us said: not you, not here. Not here.

Planted, each, many moons past, we are unhalted. Our growth in both directions, in four directions, embracing all that we are. The flower people. Retracing familiar steps, along the curve of that thread, the lines of the river, the shape of our hearts.