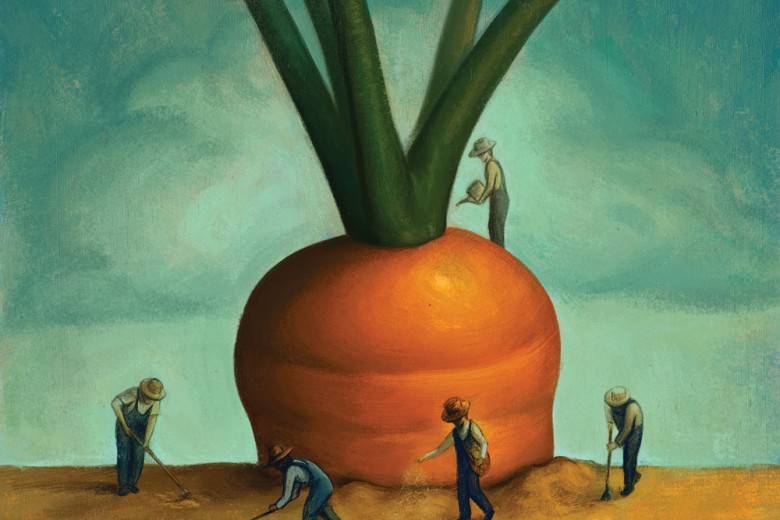

Between the 17th and 19th centuries, the saying went that the Grand Banks fisheries of Newfoundland were so full of cod that a person could walk on water. It was this belief in bounty that 20th-century capitalists and governments used to justify unimaginable fishery industrialization. As fears grew over this expansion, Joey Smallwood, premier of Newfoundland from 1949–1972, exploited a populist rage against Confederation, and insinuated that Newfoundland cod could be as great as Canadian oil were it not for the bureaucracies and centralizing ethos of the Canadian government: “I am ashamed and angry to say it, but the altogether stupid, bungling, inadequate effort of Great Canada to assist the Atlantic fishing industry (which is potentially almost as valuable in dollars and cents and much more valuable in numbers of families that can be supported than the oil industry of Alberta) is a reproach to a great and progressive country,” he said. “The present Minister of Fisheries told one very prominent Newfoundlander that it wouldn’t matter if the Newfoundland fishermen had to leave the fisheries, because they could always find work in some other part of Canada.”

Strikingly, Smallwood picked up on a growing tension between fish and oil in the province, as the rise of the latter came with the collapse of the former. The fishery’s semi-privatization to prevent debt default in the 1980s represented the final death rattle of the cod fishery, and in 1992, John Crosbie, Canadian minister of fisheries and oceans, announced its shutdown, contributing to an exodus and continuous population crisis across Newfoundland and Labrador, as tens of thousands of families lost their income almost overnight.

As of 2015, the oil and gas industry accounted for 16.7 per cent of GDP in Newfoundland and Labrador, with only 7,000 employed per year in the industry since 2016 – the inverse of the former cod fishery’s high-employment-to-low-GDP ratio. Despite this, the myth of permanent job creation that accompanies the fossil fuel economy continues, a distraction from the potential impacts of economic recession and marine pollution, normalizing the growth of precarious labour and environmental crisis globally.

Fishery crisis and fossil-fuel extractivism continue unabated across the Atlantic, from Ireland’s west-coast fishing communities’ struggles with Shell’s Corrib gas pipeline project to the monopolization of the Scottish fisheries.

Newfoundland is not exceptional in this dynamic. Fishery crisis and fossil-fuel extractivism continue unabated across the Atlantic, from Ireland’s west-coast fishing communities’ struggles with Shell’s Corrib gas pipeline project to the monopolization of the Scottish fisheries, its people now working in offshore oil to make ends meet. While Nordic redistribution of petrol revenues has fuelled a more benevolent image of the petro-state, Venezuela and Nigeria have reaped little benefit from their immiseration in oil extraction. Like a new Mammon offering infinite prosperity, the lure of hydrocarbon riches inevitably trumps the significantly lower value contribution of coastal fisheries and their communities, as corporations and powerful states engineer economic dependence on fossil fuel extraction to keep oil cheap for core nations.

In October 2016, I participated in the “Petrocultures” conference at the Memorial University in Newfoundland, which focused on the place of offshore oil in contemporary life and the possible futures of a world after oil. As part of the conference, a group of us, mainly academics and students of cultural studies, took a guided tour of the Hebron oil platform construction facility at Bull Arm. Near the water-based construction sites, our tour guide pointed toward a village across the lake, several of whose inhabitants now make supplemental income by renting rooms to construction workers. Knowing about damage to fishing equipment in Irish waters caused by pipe-laying ships, I asked about clashes with the fishers of the village and incidences of fishery equipment damage during the site’s construction. The guide explained that Hebron provides generous settlements in the case of such events, which, she assured me, were rare. As my fellow tourists complained about the lack of views of the oil platform, as well as their uncertainty as to its scale and operations, the tour guide laughingly replied, “The fish have a great view.”

As my fellow tourists complained about the lack of views of the oil platform, the tour guide laughingly replied, “The fish have a great view.”

Certainly, Newfoundland is in a peculiarly strong position to witness the accretive effects of an oil economy as it jostles with a precarious fishery sector – as oil power revolutionized fishery practice across the 20th century through the boat, the trawler, and the gill net – toward the eventual collapse of cod stocks. But the guide’s comment also says something about oil’s oddly invisible presence, in that a two-hour tour about oil managed to say virtually nothing about petroleum, relying on anodyne anecdotes in place of factual information. Despite being a hundred metres from the construction platforms, many of us later realized that we left the tour with little understanding of the gravity-based structure through which oil is extracted at the Hebron offshore site. The tour guide put up a smokescreen in the most playful, innocuous fashion, ignoring the issues of environmental destruction and the boom-bust dynamics of an oil-dependent economy. But this is only one part of the fishy story….

Following my foray into the murky world of oil PR, I took a drive around the Avalon Peninsula, visiting many of its coves and inlets, to see how the fishery continues to function. Tourists often come to this region to go out on a motorized vessel and jig for cod for the day. By participating in the limited extraction of cod, the tourist gets an important history lesson on the dangers of unrestricted extraction, though there is a concern that such lessons give an inaccurate picture of the trauma of fishery collapse. In picturesque Petty Harbour–Maddox Cove, for example, cod-jigging tours allow tourists to experience a day out on the sea catching cod, after which a fisher will gut and salt the cod, explain the process, and then the fish is stored in a freezer box to be brought home to the mainland. The village also sells jams and cakes in a local store, and fresh cod and chips in the restaurant. Petty Harbour is just off the “Irish Loop,” a scenic drive around the Avalon Peninsula that, while providing infrastructure for the development of the tourism economy, obscures the scars of mass emigration and peripheralization. We have our own version of this in Ireland, the “Wild Atlantic Way.” The people there are exceptionally friendly and chatty, but their livelihoods are dependent on an industry that replicates the labour and life relations that defined such inlets for centuries, and a barely palpable sense of loss lurks under the picturesque surface.

At nearby Brigus South, I spoke to a crew of crab fishers about this in order to understand where the fishery might go beyond the tourism trade. They mentioned that a private capitalist pays for their gear and the upkeep of their boat in exchange for a cut of profits, thereby shielding them to some extent from the volatility of the market. One fisher explained to me that his son left the port for offshore oil work, since, in his words, “There’s no money to be made at home.” That conversation was just over a year ago. In light of concerns over the crab fishery’s unsustainable expansion (like the cod before), I wonder now if that fisherman has followed his son into offshore work, reversing an intergenerational fishery livelihood in favour of a precarious, oily one.

Though government and popular support for private oil investments or public shares in oil extractivism continues, even the staunchly free-market Martin Prosperity Institute asks, “is the oil economy at risk of collapsing like the cod economy once did? In other words: is oil the new cod?” A more interesting question might be how is oil the new cod when the collapse of the fishery created such powerful distrust in corporate governance? I attended the permanent ExxonMobil exhibit at the Johnson GEO CENTRE in St. John’s in search of an answer, and beneath the amicable exterior, found one.

The exhibit describes the scientific processes of oil and gas extraction, its economic importance, as well as oil rig safety regulations – a friendly, vague education experience that pairs well with the promise of exotic, “authentic” nature-tourism experiences that Newfoundland is famous for. Midway through the exhibit, an interactive game tasks children with putting together the perfect amount of different energy forms (carbon, wind, tidal, etc.) while pleasing tourists, locals, and bankers. A bank balance counter at the bottom of the screen demonstrates the expense of certain forms of energy production over others, naturalizing a correlation between resource ownership, provincial futurity, and capitalism.

When I played, hydro power incurred the wrath of the game’s fisher and tourist characters alike, meaning that I had to redraw my plans to finish the game correctly, balancing carbon and non-carbon energy outputs for a positive outcome. The game shows how oil becomes the new cod, promising family values and provincial wealth, obfuscating the internal contradictions of capitalism, which manifest through pollution, through unemployment, and through the generalized precarity of neoliberalism. Fossil extractivism has become naturalized through “amicable oil” (my term), an ideology that includes user-friendly instructive games, and positive, chatty tour guides, excusing and concealing the casualization of labour in the oil economy, as well as the accompanying levels of substance abuse in Newfoundland’s increasingly mobile workforce.

When I played, hydro power incurred the wrath of the game’s fisher and tourist characters alike, meaning that I had to redraw my plans to finish the game correctly, balancing carbon and non-carbon energy outputs for a positive outcome.

As shown by numerous oil busts and disasters like the May 2016 Fort McMurray wildfire, the ecologies of oil extraction ultimately implode. Yet the catastrophic events burned into people’s minds by images of tanker spills and towns turned into raging infernos are only particularly obvious manifestations of environmental violence. In fact, capitalism has always expanded via the “slow but inexorable loss of human and non-human lives, dignity, habitat and livelihood [which] have become a part of the natural life cycle of historical modernity,” in Upamanyu Pablo Mukherjee’s terms. While neoliberal “greenwashing” facilitates capitalist accumulation in the relatively short term, advertising “sustainability” as a more ethical form of capitalism, people continue to experience the contradictions at the fishery and oil frontiers through long-term socio-ecological collapse. This dynamic shows no sign of abating. Environmental historian Jason Moore goes so far as to suggest that capitalism operates through “a general law of overpollution,” among other forms of violence, including racism, gender discrimination, and colonialism.

As such, massive investments in hydro power, as in Muskrat Falls, are not solutions to systemic crisis, as they ignore Indigenous rights and inevitably toxify land and water, belying a colonialist mentality that dehumanizes and delegitimizes humans, animals, and the environment. What is needed in the short term is a tourism sector that privileges education and information, not obfuscation. Furthermore, instead of monopolization and top-down, state-scientist directives, a horizontal, long-term fishery management model embedded in seaboard communities could revitalize the industry.

Eventually, a whole new way of thinking needs to emerge to challenge narratives of capitalist permanence, instead of replicating and reinforcing extractivism, and a combination of horizontal management and Indigenous governance is necessary for this transition. More generally, we need to continuously historicize and publicize the long-term consequences of untrammelled exploitation and accumulation, which goes far beyond fish, oil, tourism, or Newfoundland, but into the very conditions of possibility for life itself. Ultimately, we must demystify the narrative of “no alternative” through which capitalists and governments continue to avoid accountability, and unveil the connections, correlations, and counterpoints that represent the limits of capitalism itself.