We are by now familiar with the story of the crushed American dream: the expansion of free trade, the attendant outsourcing and capital migration to Mexico, and advances in technological automation combined to pull the rug out from under the feet of the American manufacturing sectors in Detroit, Gary, Youngstown, Buffalo, Flint, and Cleveland. With capitalist bootstraps permanently slouched out of reach in those blue-collar towns, one thing was clear: the economic devastation of the working class was an effect of the forces of globalization, international profiteering, and free trade.

A story not often told in those reminiscent conversations is that of Oshawa, a small Canadian city in southern Ontario, 45 minutes outside of Toronto. From the early 1900s, Oshawa was built primarily by the automotive giant General Motors. GM made Oshawa home to some of the largest branch plants in the country, christening the small city as the automotive capital of Canada. A strong labour spirit pervaded the municipality, painting it as a picturesque “union town.”

Local 222 – once the United Auto Workers, then Canadian Auto Workers, now Unifor – lived through the rise and fall of Oshawa’s manufacturing sector. The union debuted during the 1937 Oshawa strike, which historian Irving Abella once called the “birth of industrial unionism” in Canada. In the following decades, auto workers militantly held wildcat strikes, organized plant occupations, and protested high interest rates in Ottawa. In 2008, union members set up a four-day-long blockade around the now-closed truck factory to protest the forthcoming plant closure and loss of 2,600 jobs. The plant closed, but workers took what solace was available in winning negotiations for buyouts and retirement packages.

Oshawa resembles a miniature version of Detroit – both in its rise and its fall. In the 1980s, GM’s four plants supplied over 20,000 jobs in Oshawa. Today, that number is a meagre 2,600.

Automation breakthroughs in the 1990s severed the workforce, and as the free-trade trend intensified, capital left town. With it disappeared much of the community that had developed.

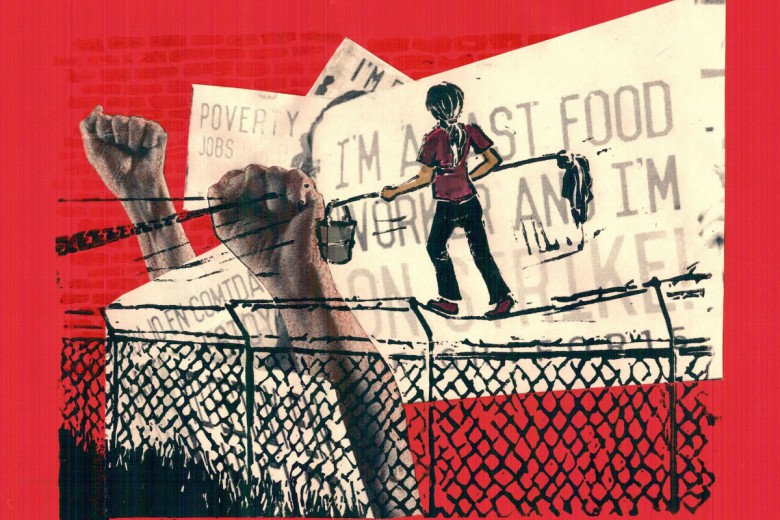

Since experiencing the drastic decline in automotive jobs, Oshawa’s levels of child and adult poverty, inadequate housing, and precarious employment have spiked. Food bank use in Durham Region rose 21 per cent between 2009 and 2010, in line with deep cuts to social assistance. In 2012, 13.8 per cent of adults in Oshawa lived below the poverty line, and the following year, statistics show that almost 20 per cent of the city’s children did.

At the centre of these issues is the city’s economic transformation – from being secure and rooted in manufacturing to becoming precarious and service or knowledge sector-based.

Despite 2014 being a “banner year” for job creation – with the growth of available jobs with Lakeridge Health and local educational facilities – former manufacturing workers are having difficulties filling these knowledge-based vacancies. Asymmetry between skills required for the new kinds of work and the skills honed by the long-standing residents who previously worked on the assembly line is, according to the Social Planning Network of Ontario (SPNO), “forcing residents into precarious employment situations.” Many of these precarious situations have emerged in the retail sector, which has witnessed significant growth in Durham.

“New knowledge-based labour markets in the riding have not directly replaced the manufacturing opportunities that previously existed,” states the SPNO’s Action on Poverty report. “The community is facing growth in one sector and decline in another – a situation that is creating conditions of poverty and hardship for many residents.”

New Student Leadership

In response to the ongoing precariousness, Local 222 recently began organizing service department workers at Mercedes-Benz Durham, cleaners at GDI Services, and support staff working for the nearby student union.

The Durham Region Labour Council (DRLC) also continues to act as a meeting place for the community’s broad working class, as it has since 1942. It still holds its monthly general meeting every second Tuesday in the hall of Local 222, where executive members, activists, students, and workers connect to speak about issues in the community and to organize.

But fresher forces for social justice have recently arisen, in the form of student politics. One representative of this shift is Jesse Cullen, a community organizer and the president of the Oshawa-based Student Association (SA) of Durham College and the University of Ontario Institute of Technology.

Before returning to school as a mature student, Cullen had lived in the “slums” of the city on social assistance, which gave him what he calls a “working-class orientation.” Blending his own experiences with the critical theories from his criminology studies, he began to get involved in addressing community issues that connected the labour movement with student politics.

The SA has reoriented itself toward social justice, which yielded some criticism after years of conservative administrations, he says.

“There are always some folks who do not believe the Student Association should be involved in activism or left-wing political organizing,” he observes. “There is a long-standing culture of collusion between ‘student leaders’ and the administrations on our campus. And because of the void of effective and combative student leadership, there is a natural backlash against anything that challenges that tradition of passive student leadership. But, that’s why we organize. That’s why we struggle.”

Only recently has the SA become involved in calcifying bonds between the deeply rooted Oshawa labour movement and the student movement, Cullen says. The first campaign between the two was Drop Tuition UOIT, which organized a student walkout last March.

“What [students and labour] have in common is our interest in controlling our own labour, and the fair distribution of wealth and resources in our community. Our staff at the Student Association is also unionized with Unifor Local 222, and we think that relationship is extremely important, too. For example, Local 222 also represents bus drivers with Durham Region Transit [DRT],” he says. “So, when DRT recently announced plans to hike student bus fares by 25 per cent, Unifor Local 222 came out against it. There are many opportunities like that, where our interests intersect and where we can pool our collective resources and influence to make life better for students and workers.”

“We definitely look to the history of militant organized labour in Oshawa as a model and a proud tradition,” Cullen insists.

Broader Struggles

But there are difficulties that come with being a predominantly “white working class town” – the progressive conversations, Cullen notes, “end at wealth redistribution. People’s eyes glaze over” in conversations about racism, sexism, and homophobia in the community; support of left-wing labour politics does not, after all, guarantee engagement with other issues of social justice and equality. Such attitudes can clash with the diverse student populations of UOIT, Trent, and Durham College, Cullen says.

“As a student union, we represent international students, many racialized students, and other equity-seeking groups that, I think, are less present in the membership of traditional trade unions,” he says. “Particularly as young people have less and less access to unionized workplaces, and the demographic of the remaining unionized sections of the Canadian workforce is aging, there exists this tension between protecting what those older, typically white workers have – like pensions and benefits – and broadening the labour movement to include young workers, racialized workers, women, and other folks who don’t have access to those kind of workplace benefits and protections.”

This tension is not unique to Oshawa. Charlotte Yates, professor emeritus at McMaster University, raises questions about the “strategic change” needed within union structures and organizing tactics given the changing makeup of the labour movement. “Our communities are racially and ethnically diverse and the labour force is changing accordingly. To date, many unions have failed to keep pace with these demographic changes. Unions are therefore in danger of being out of touch with many workers.”

These conditions, Yates says, precipitate a need to “overcome a skilled trades history of exclusivity and domination by Anglo Saxon members and practices in the face of a rapidly changing … labour force.”

Outside of the local labour movement, the SA has been involved in its share of community struggles. “There’s a student perspective on every issue, and trying to find alliances and build strategic relationships with folks in the community [is important],” Cullen affirms.

The Student Association draws links between the many experiences of marginalization present in Oshawa, and they organize in solidarity with diverse movements and causes, including No One is Illegal, democratic electoral participation, LGBTQ rights, and prisoner rights.

Cullen recognizes that the student population represents a microcosm of Oshawa’s broader social struggles. In particular, he notes, “poverty [in Oshawa] is a huge issue for students. There’s 21 per cent youth unemployment, we have incredible challenges in access to child care, access to good-paying jobs, and [facing] precarious work.”

Such economic shifts and growing poverty have also instigated serious housing issues, Cullen says. He slams the political priorities of city council, who, he says, sold off the city’s social housing units that were $3 million behind in repairs while doling out tax breaks and cutting development costs for the builders of a new Holiday Inn.

Cullen also mentions other movements happening in the city. Tenants in Oshawa’s poorer south end have begun organizing as the South Oshawa Community Association to address some of their “deplorable” living conditions, Cullen says, like “bed bugs, maintenance issues, and infestations.” He says these problems are no longer centralized in urban centres as they traditionally have been and are readily apparent in suburbs like Oshawa.

In addressing these issues, Cullen says the next step for community leaders, students, and organizers is “building capacity” for change in the city through “block-by-block organizing” and “establishing democratic spaces.” Having a place for citizens to be heard and to set the agenda is crucial, he says. He’s also focusing on inviting those who haven’t engaged in such organizing before.

“We’re getting out and saying, ‘hey, [signing] this petition is one thing – but it’s not going to change the world.’ We’re getting continual engagement that way,” he maintains, noting that they’re laying the foundation for broader, more intersectional and accountable social change.

We Are Oshawa, an activist group on whose executive board Cullen used to sit, has employed this tactic. The work of WAO is largely canvassing door-to-door between elections to raise awareness of issues like affordable child care and public services; it most recently campaigned for the Save Canada Post campaign, which Oshawa city council ultimately endorsed. Cullen says the same dedication will be needed to “push some of the right-wing politicians” to move on Oshawa’s pressing issues.

Despite the current barriers to change, Cullen maintains that he admires Oshawa’s “resiliency and working class character.” He remarks, “It’s small enough to see people you know every day and know the names of your servers at the local restaurants, but it’s large enough that it’s ‘on the map.’” When Oshawa does something, Cullen says, people notice – and local activism is no different.