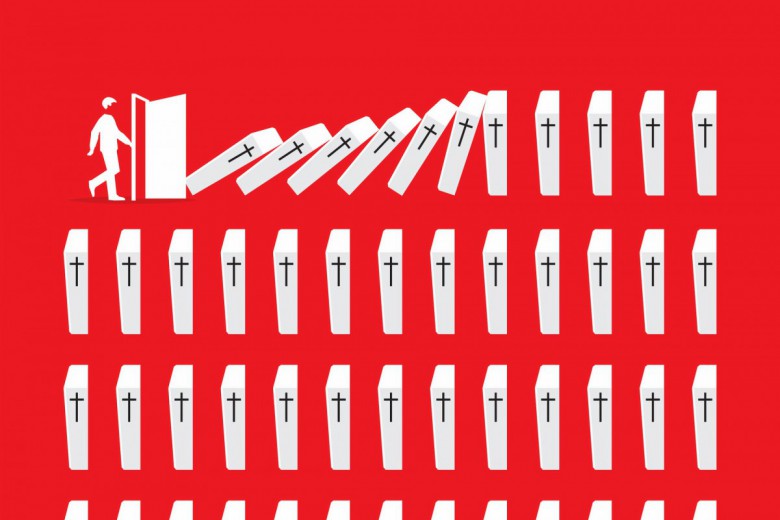

Canada is the only country with a universal public health-care system that does not include coverage for prescription drugs. According to 2010 data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information, Canada ranks below 23 countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in the percentage of prescription drug expenditures that are publicly paid. Only the United States sits below Canada. Just 29 per cent of the Canadian population in the country is covered by a public drug plan, and 10 per cent of the population lacks any type of coverage. In a 2015 Angus Reid poll, almost one-quarter of respondents or someone in their household said they did one or more of the following in an attempt to mitigate the cost of drugs: decided not to fill a prescription, decided not to renew a prescription, or took steps to make a prescription last longer.

The labour movement is among the most prominent advocates of a national pharmacare plan today, but the idea was first recommended in the 1964 report from the Royal Commission on Health Services (also known as the Hall Report, after its chair, Justice Emmett Hall). In calling for drug coverage, Hall noted, “In view of the high cost of many of the new life-saving, life-sustaining, pain-killing, and disease-preventing medicines, prescribed drugs should be introduced as a benefit of the public health services program.” Hall’s position on pharmacare was echoed by the National Forum on Health in 1997 and in the 2002 Romanow Commission report.

The introduction of extremely expensive drugs – for example, the cystic fibrosis treatment KALYDECO initially priced at $300,000 per year, or Soliris, a $700,000-per-year medication for a rare disease involving blood cells and kidneys – has provoked the call for drug coverage for the entire population. Reports supporting this position are piling up, and 87 per cent of Canadians are moderately or strongly supportive of adding prescription drug coverage to the package of benefits offered under medicare.

The Liberal government has not been enthusiastic about such a move. Jane Philpott, the former federal minister of health, told the 2016 annual meeting of the Canadian Medical Association that such a program is unlikely to be priority for the government. A report commissioned by the Canadian Pharmacists Association recommended against a national publicly administered pharmacare plan on the grounds that it is “impractical, disruptive and [its] potential for cost savings is overstated.”

While the influential naysayers have the ear of politicians, a pharmacare plan makes sense on the basis of both equity and costs. Here are six reasons why.

1. Private plans are not doing a good job of ensuring that patients receive their required drugs

Twenty-four million Canadians (67 per cent of the population) have some form of private insurance coverage for medications, and 31 per cent of total prescription drug expenditures in Canada are covered by private insurance. But these plans have no incentive to control drug prices or overall expenditures. In fact, between 2003 and 2012, private expenditures rose faster than public expenditures in eight of the 10 years. One of the key reasons that private insurers have little concern for costs is because most private plans are just administered by insurance companies that take a percentage of what is spent. The more the private plans cost, the more the insurance companies get.

2. Public plans are needed to cover more people

Provincial plans pay about 32 per cent of total prescription drug costs in Canada, and federal funds pay an additional 2.5 per cent. The individual prescription drug programs in each province vary considerably in their design, in terms of who is eligible for coverage, which drugs are covered, and how much people have to pay in the form of deductibles, copayments, and user fees. Provincial plans are based on age (usually covering people 65 and older), income level (coverage on a sliding scale below a certain individual or family income), and employment (if employers offer health benefits to their workers, then they must offer drug insurance, and employees are obligated to purchase the insurance). In addition, all provinces cover social assistance recipients, although sometimes the recipients are required to pay a copayment.

But the amount that people have to pay out of pocket varies widely by province. For example, a 65-year-old woman whose family income was below the national average and who was taking medications for diabetes, hypertension, and insomnia would pay out of pocket from $8 in Ontario to $503 in Manitoba. A 40-year-old social-assistance recipient requiring drugs for hypertension and high cholesterol would get their drugs for free in one province but would pay up to $200 in another. These figures are based on December 2006 drug plans, and while plans have changed since then, it is likely that this level of variation still exists.

Copayment: Drug plans typically do not cover the entire cost of a prescription. The amount that patients have to pay is called a copayment. In addition to covering part of the cost of the prescription, public and private drug plans may also require patients to spend a certain amount on medications before insurance starts. This amount is termed a deductible.

Discontinuation refers to whether patients did anything to make their prescription last longer, did not fill a new prescription, or did not renew a prescription.

Formulary: A formulary is a list of prescription drugs that a drug plan (private or public) will cover. In the case of public drug plans, the decision about which drugs to cover is made by an expert committee based on the safety, effectiveness, and cost of the drug. Private plans often pay for any drug approved by Health Canada but may also have a formulary.

Across Canada, about 9.6 per cent of people who need medications don’t take them because they are too expensive, but this figure hides significant differences within the country. Not surprisingly, the cost barrier to medications is significantly related to income and having insurance coverage. Only 3.6 per cent of people with insurance and a high annual income of over $80,000 face cost-related non-adherence to medication, while that number is 35.6 per cent – 10 times higher – among people with an annual income of less than $20,000 and no insurance. Even among those who are in the top 20 per cent of the income range, insurance is still important. The discontinuation rate for those in this income bracket who lacked insurance was just shy of 15 per cent.

3. We need more than just the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance

In 2010, in an attempt to deal with high drug prices, nine of the provinces formed the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA). The idea was to combine the bargaining power of all the public drug plans to negotiate a lower price for both brand-name and generic drugs. To date, the pCPA has negotiated well over 100 price deals with pharmaceutical companies and, according to the organization, public drug plans are saving about $712 million annually because of those deals.

The pCPA initiative is promising, but its negotiating abilities are also limited by Canada’s fragmented drug payment and coverage system. Each province and territory structures its drug plan differently: some provinces enter into confidential pricing agreements with companies, and some make the final decisions on whether to cover a particular product. Glaringly, the bargaining power of the pCPA is limited because it cannot affect private drug plans, which cover 31 per cent of costs in Canada. An even greater problem is that the discounts negotiated by the pCPA do not apply to people who lack any insurance and have to pay out of pocket – that is, those who often need the discount most.

4. A public plan will make sure that people get access to important new drugs

To highlight what it sees as an unjust delay in getting new drugs onto provincial formularies, the lobby group for the large pharmaceutical companies, Innovative Medicines Canada (previously Rx&D), and its organizational allies periodically produce reports comparing provinces in terms of the percentage of new drugs that they list on their formularies and how long the listing process takes. The message in these publications is essentially the same: not enough new drugs are listed, and those provinces that do list new drugs are slow to do so; the cumulative effect, they purport, is that Canadians are not getting the best care possible. The 2011–2012 Rx&D report reads: “Canadians do not appear to benefit from access to the full range of new pharmaceutical innovations.” Recent analysis from the Canadian Health Policy Institute, a free-market think tank, makes the point that “private plans provide faster and better access to the most innovative treatment options for patients.”

If most new drugs offered significant therapeutic benefits over existing products, then there might be some validity to the charge that these slow-to-list public plans are harming patients. But analyses of the products that Health Canada approves do not support this argument. Out of 479 new drugs that Health Canada approved between January 1, 1995, and March 31, 2016, only 51 were major therapeutic advances; the remainder offered, at best, moderate advantages over already existing products. Innovative Medicines Canada and the Canadian Health Policy Institute clearly overstate how many new drugs are actually therapeutically innovative and important. A universal pharmacare plan, however, would cover those that are important new developments.

5. We can afford pharmacare and save money

The reports from both the Canadian Pharmacists Association and the Canadian Health Policy Institute allege that pharmacare would be too expensive; the latter asserted that pharmacare will shift $13.2 billion in private prescription drug-related costs onto taxpayers. But a recent peer-reviewed report published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal concluded that universal public drug coverage would reduce total spending on prescription drugs in Canada by $7.3 billion because of lower prices from stronger negotiating power, more use of generic substitution and “cost-effective product selection through a population-wide, evidence-based formulary,” and overall costs to government would increase by only about $1 billion. Some of the additional government cost from increased public coverage would be partially offset because the government would no longer be paying for private insurance for public employees.

6. Pharmacare will do more than just save money

It is true that economics plays a major role in pharmacare discussions, but pharmacare is not just about money. The more financially invested governments are in a pharmacare scheme, the more they want to ensure that scheme is running efficiently and delivering value for money, and not just funnelling public money to private for-profit companies. In the case of pharmaceuticals, this means countering the $500 million that drug companies spend annually here in Canada on promotion, trying to influence how doctors prescribe. Studies done worldwide show that when doctors listen to the companies, there is an association with more frequent, more expensive, and less appropriate prescribing.

By way of example, Australia has had a national pharmacare plan since the late 1940s; as the cost of the plan increased, Australian governments from both the centre-right and the centre-left recognized the need to provide objective evidence on the effectiveness and safety of medicines to both doctors and patients. As a result, in 1998 the Australian government established the independent National Prescribing Service (now NPS MedicineWise) to undertake work in the quality use of medicines. The underlying philosophy of the organization is to give health professionals and consumers access to evidence-based information and other supports for good prescribing and decisions about medicine use. NPS MedicineWise conducts regular educational visits with general practitioners and group training with pharmacists, nurses, and other health professionals. It encourages adherence to prescribing guidelines and facilitates better communication with patients regarding a range of health and medicine issues. It also works extensively with consumers, conducting research and devising a range of interventions to overcome areas where knowledge is lacking or where a change in behaviour would produce better health outcomes.

In 2015, NPS MedicineWise received about AU$50 million annually from the Australian federal government to provide evidence-based information and education to 24,000 participating general practitioners. Programs sponsored by NPS MedicineWise saved the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme about AU$70 million in 2014 and have improved prescribing in a number of areas, including secondary stroke prevention.

Pharmacare is another step in providing a social safety net for Canadians and building on the publicly funded health care system that we currently have. It helps ensure that people who become ill as a result of the social determinants of health – poor housing, precarious employment, unequal distribution of wealth, sexism, and racism, among others – are able to receive medications that can help them.

Evidence about pharmacare points to an obvious conclusion: a publicly run universal pharmacare plan is the best way to ensure that patients get the medications they need at a cost the country can afford.

This article was adapted from Joel Lexchin’s “Six myths about pharmacare,” which appeared in issue 37 (2&3) of Health Law in Canada.