On January 8, 2015, the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) held a meeting in Ottawa. They invited the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Ottawa police, Gatineau police, representatives from a pulp, paper, and personal care company called Domtar, and a construction company called Windmill Developments.

At the time, Windmill and other developers were planning to build Zibi – “a world-class sustainable waterfront community” of condominiums, stores, and offices – on Akikodjiwan, a sacred Algonquin Anishinabeg site in downtown Ottawa and Gatineau, after demolishing the old Domtar building on the site. Meanwhile, anti-colonial activists were ramping up their opposition to the Zibi development. And – as the meeting between four police forces and the industry representatives indicates – the cops were also preparing for the resistance.

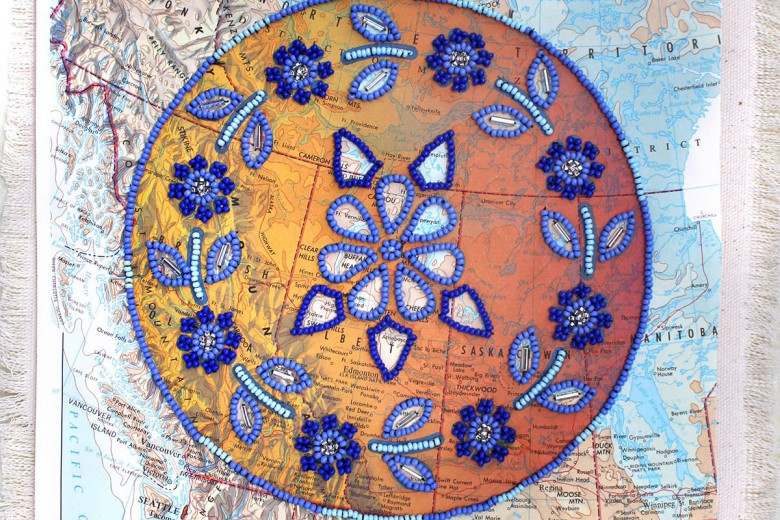

The sacred site, Akikodjiwan, includes Chaudière Falls and the Chaudière, Albert, Amelia, Victoria, Wright, and Coffin islands. (Coffin Island is now submerged, and Wright Island is considered part of the Gatineau shoreline.) These islands sit in the middle of the Kitchi Zibi (Ottawa River), between the cities of Ottawa and Gatineau.

And – as the meeting between four police forces and the industry representatives indicates – the cops were also preparing for the resistance.

Dream Unlimited Corporation and Theia Partners (an offshoot of Windmill Developments) – the settler developers – stand to make hundreds of millions by building condominiums on Akikodjiwan. Construction on Albert and Chaudière islands has already begun.

In 2016, the Kitigan Zibi band council filed a land claim that included the Chaudière, Albert, and Victoria islands in the Ottawa River, and there are ongoing discussions about the area between the government and representatives from the Algonquin tribal councils. A group called the Traditional Grandmothers of the Pikwakanagan has also filed a legal case in Ontario’s Superior Court of Justice asserting Indigenous title to the islands.

Activists have so far focused on pressuring municipal and federal governments to stop the condominium construction. Despite their efforts, Zibi is still moving forward. There has been talk of blockading or occupying the construction site, but it hasn’t happened – yet.

Anishinabe-aki

If you stand on Albert or Chaudière islands, you can see Canada’s Parliament squatting on a small hill to the east, overlooking the Kitchi Zibi. From there you can also see the large, ugly brown building that houses Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs (CIRNAC) and Indigenous Services Canada (ISC). The two buildings – one the beating heart of the federal government, the other of the colonial bureaucracy – lie on stolen Anishinabe-aki (Anishinabe land).

Douglas Cardinal, a renowned Indigenous architect, activist, and Elder is at the centre of resistance to the Zibi project. He describes the significance of Akikodjiwan: “These beautiful, sacred waterfalls and islands lie at a symbolic confluence of waters: The rivers flow into the centre from the South, West and North and in turn flow to the East. Similarly, our own ceremonial lodges embrace the four directions and are opened to the East. Furthermore, the Chaudière Falls creates a great kettle; a whirlpool that brings water deep into the earth. With the uprising mist and the surrounding rock forms, the falls appear as a sacred pipe, sculpted by the Creator.”

“With the uprising mist and the surrounding rock forms, the falls appear as a sacred pipe, sculpted by the Creator.”

The Kitchi Zibi watershed sits within Algonquin Anishinabeg territory. The Algonquin Anishinabeg have never ceded or surrendered any part of their lands. King George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which recognized Indigenous ownership of large parts of Turtle Island (which settlers refer to as North America), and stated that land could only be acquired by the Crown at public meetings.

According to Algonquin Anishinabekwe author Lynn Gehl, the Royal Proclamation was ratified by the Algonquin Anishinabeg and 23 other Indigenous nations at the 1764 Treaty at Niagara. But beginning in the 1800s, American and British settlers defied the Proclamation and began stealing Algonquin land in the Ottawa Valley by applying for tracts of land through the Crown. As they settled near Akikodjiwan, they set to work damming the Kitchi Zibi and cutting down the old-growth forests for their fledgling lumber industry.

In her book, The Truth That Wampum Tells, Gehl details the colonial dispossession of the Algonquin Anishinabeg, as well as Algonquin resistance. She writes, “Between 1840 and 1870 large grants of Algonquin land were awarded to timber companies, and through the Public Lands Act of 1853 one hundred acres [per person] of Algonquin land was provided free to settlers.” The damming of the Kitchi Zibi and the lumber industry’s pollution devastated the river. For example, the American eel, which was a staple of the Algonquin Anishinabeg diet, is today considered endangered – and its population continues to decrease.

As they settled near Akikodjiwan, they set to work damming the Kitchi Zibi and cutting down the old-growth forests for their fledgling lumber industry.

The felling of the old-growth forest also hurt the ecological health of the region, greatly reducing the populations of wild animals that the Algonquin hunted. Diseases brought by Europeans, and war with the Haudenosaunee (who were aided by the Dutch and British) decimated the Algonquin Anishinabeg population, and they were pushed to the margins of their territory. Today the Algonquin Anishinabeg land base is 208 square kilometres, a tiny fraction of the 146,300 square kilometres that make up their territory.

Sacred sites, Settler Law

Akikodjiwan is not the only sacred Indigenous site in Canada threatened by development. Many sacred sites in Canada are not controlled by the Indigenous nations that venerate them; these sites are usually considered Crown land, or, as in the case of Akikodjiwan, private property.

The Ktunaxa, a West Coast Indigenous nation, went to the Supreme Court of British Columbia in 2014 to prevent a proposed year-round ski resort from being built at the heart of Qat’muk, one of their sacred sites. In Qat’muk, “the Grizzly Bear Spirit, was born, goes to heal itself, and returns to the spirit world,” a declaration written by the Ktunaxa explains. They argued that the development infringed upon the Ktunaxa nation’s “freedom of conscience and religion” under section 2 (a) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. But the court ruled against the Ktunaxa, asserting that since the government had fulfilled its duty to consult the nation, the construction could proceed.

I speak with Senwung Luk, a lawyer with the law firm Olthuis Kleer Townshend (OKT), who specializes in defending Indigenous sacred sites. He tells me that the root of the issue “goes back to the assertion of Crown sovereignty. It goes back to the idea that the Crown has the right to decide what happens on the land, even if settlers have never been there.”

These sites are usually considered Crown land, or, as in the case of Akikodjiwan, private property.

He continues, “Why does Canadian law consider [Qat’muk to be] B.C. Crown land? This is tied up in [a] process that is happening all across Canada, of the Crown assertion of sovereignty undermining Indigenous decision-making about these kinds of places.”

On his blog at OKT, Luk compares how Indigenous and settler sacred sites are treated under Canadian law: “One of the ways to understand this relationship is to look at how English law […] has treated sacred sites in England,” he writes. “[S]acred sites are defined by the Church of England under ecclesiastical law, not by the government itself. Generally speaking, civil law doesn’t apply to those sites. The governance of the site is up to the Church.”

“When the government wants to develop a burial site, for example, it usually will get permission from the Church to do so,” he concludes.

Canadian law is largely based on English law. But compare the Church of England’s control of sacred sites with the decision by the municipality of Oka to construct a golf course on top of a Kanien’keha:ka burial site. When Kanien’keha:ka warriors set up barricades to prevent the construction of the golf course, the Quebec court issued two injunctions ordering the warriors to remove the barricades – leading to the 1990 Kanehsatà:ke Resistance (also known as the Oka Crisis). Christian churches are respected and consulted, while Indigenous spiritualities are disregarded and trampled upon.

Indigenous territory – even lands like those of the Algonquin Anishinabeg that have never been surrendered – are considered to be subject to the authority of the Canadian state through the concept of the “Doctrine of Discovery.” In international law, the Doctrine of Discovery holds that exclusive control over a region is assigned to the first European Christian country whose representatives explore that area.

“It goes back to the idea that the Crown has the right to decide what happens on the land, even if settlers have never been there.”

Luk expands on the implications of this practice on the OKT blog: “First, unless an Indigenous community proves to a court’s satisfaction that it has exclusive occupation or control of a territory, the default understanding of the Canadian legal system is that that territory is Crown land, even if Crown officials and settlers have never set foot on that land. Second, even if an Indigenous community can prove that they have an Aboriginal right, Aboriginal title, or a Treaty right, that right is always potentially subject to infringement by the Crown.”

The assumptions of the Doctrine of Discovery have been referenced in Canadian Supreme Court cases. But the Doctrine also stands in opposition to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which states that Indigenous peoples have a right to their lands, and a right not to have their lands taken from them without their free, prior, and informed consent. Canada has not yet fully ratified UNDRIP, though it’s made moves toward doing so.

Settler sacred sites are usually protected from state or corporate interference because they are private property. But sacred sites of Indigenous nations that are not Crown land are likely to be the private property of settlers, as is the case with Akikodjiwan.

Policing land theft

Based on files provided to Briarpatch, obtained through an access-to-information request filed by Paul Sylvestre, a PhD candidate at Queen’s University, there were at least five police meetings about the Zibi development in 2015 and 2016.

One of those meetings, on October 27, 2015, was between five police forces – the OPP’s Aboriginal Liaison Service, the Sûreté du Québec’s intelligence section, the Gatineau police’s intelligence section, the Ottawa police’s demonstration unit, and the RCMP’s National Capital Region General Duty Protection Policing training and demonstration section. They were joined by the National Capital Commission (NCC), a Crown corporation responsible for developing the National Capital Region of Ottawa-Gatineau.

Jeff Monaghan is a professor at Carleton University and co-author of Policing Indigenous Movements. When I ask him whether he saw similarities between these meetings with developers – like the one on January 8, 2015 – and meetings between pipeline companies and law enforcement, he replies, “The parallel is right there. There seems to be a standard where a seat at the table is given to the private property owners. That’s inherently colonial. The only stakeholders that are invited into the policing meetings are the developers.”

“The only stakeholders that are invited into the policing meetings are the developers.”

Monaghan describes these types of police–industry collaborations as the “new norm.”

“The police are hearing about the developer’s branding of a land conflict as being about their private property and people disrupting their right to develop property.”

In 2017, real estate was the largest driver of Canadian gross domestic product, responsible for over a tenth of Canada’s GDP.

A series of OPP reports also record the police force keeping close tabs on protests against Zibi. OPP officers monitored and attended at least four anti-Zibi protests between May 2015 and June 2016.

Ottawa has its own police force that, until 2017, had its own specialized unit for demonstrations because of the high number of protests that happen in the capital city. The involvement of the OPP at protests in Ottawa is not routine.

In an October 2014 email, Ottawa Police Service (OPS) officer Peter McKenna wrote, “Typically we see protests for political awareness purposes in the NCR [National Capital Region] but this has the potential to lead to actual direct action locally in the form of blockades or similar initiatives if the Aboriginal community became strongly engaged on this issue.” The email was sent to Mathieu Brisson, an OPP officer who would later monitor and attend at least four anti-Zibi protests.

“They’re really trying to police the success of the movement.”

“This isn’t crime control,” says Monaghan. “This is about gathering intelligence about politics. They’re policing a politics that they’re not supportive of, that as an organization they actually have a lot of antagonism against. They’re really trying to police the success of the movement.”

Documents received from the OPS also reveal that the police force was gathering intelligence on six local activists opposed to Zibi. Their notes appear to be based on publicly available information – Algonquin Elder Albert Dumont’s blog, for example, is mentioned in the OPS’ notes.

The heavy scrutiny directed at opposition to Zibi highlights that the OPP and other Canadian police forces perceive Indigenous resistance as a greater threat than many other issues – one that is not contained to a city, but warrants the involvement of provincial police because it challenges the Canadian state. More time, money, and resources are being mobilized by the Canadian state to suppress Indigenous land defence than for other issues not connected to Indigenous resistance.

Defending the sacred

Albert Dumont is from Kitigan Zibi, an Algonquin reserve in Quebec, about two hours north of Ottawa. He’s in his 60s, tall, clean-shaven, with short, thinning grey hair. More than 30 years ago Dumont turned to Anishinabe spirituality, and it’s been central to his life ever since. Today he’s a spiritual adviser, as well as a poet, artist, and activist. He’s been at the heart of efforts to protect Akikodjiwan. Along with Algonquin Elder Jane Chartrand, he has organized annual demonstrations calling on the public, and spiritual leaders of all faiths, to protect Akikodjiwan. He’s also spoken at demonstrations, on panels, and written several blog posts about Akikodjiwan and Anishinabe spirituality.

I spoke with Dumont about the lack of respect shown to Indigenous spirituality versus settler religions. “It’s proof positive that the government of Canada, the province of Ontario, and the municipal government of Ottawa are politicians who have superiority complexes,” he says.

When I ask the mayor’s office about his support for Zibi, I’m told that, “Economic Development has always been, and will continue to be, a priority for Mayor Watson.”

“Indigenous spirituality is still something of the devil in their minds, I guess,” he continues. “It hurts me spiritually. I feel that I’m [a] second- or third-rate human being because of my spiritual beliefs. A religion could have come here from somewhere else 50 or 75 years ago, and it’s protected. They could build their house of worship somewhere and if a developer went there and said, ‘We’re gonna knock this house of worship down and where it stood we’re gonna build a condo,’ nobody would tolerate that,” he adds.

With construction proceeding on Zibi, things are coming to a head. Foundations are being dug on Albert and Chaudière islands. There is no certainty about the ultimate outcome of the 2017 land claim and the Grandmothers’ legal challenge – and, in any case, it will be years before they are resolved. Apart from taking enormous amounts of time and money, legal cases rely on the courts of the Canadian settler state for justice – courts that still use racist and colonial concepts like the Doctrine of Discovery as precedent.

Federal and municipal politicians are not listening. Ottawa’s mayor, Jim Watson, has made it clear that he values economic development, not Indigenous spirituality. When I ask the mayor’s office about his support for Zibi, I’m told that, “Economic Development has always been, and will continue to be, a priority for Mayor Watson.”

With a federal election approaching, anti-Zibi activists have been planning to make this an election issue for federal members of Parliament. In the absence of other options, blockades and occupations might be the only course of action available to Algonquin Anishinabeg activists and their allies to halt the construction of condominiums on sacred Akikodjiwan.