Anne Docherty is a popular educator based in the Upper Skeena region of northwest British Columbia on the traditional territories of the Gitxsan. Originally from Scotland, Anne came to work in British Columbia’s north where the Gitxsan still constitute over two-thirds of the population of 6,000 living on their lands. Sitting down with Briarpatch, Anne reflected upon the formative influences on her understanding of popular education and how she uses popular education as a framework to advance decolonization and regional self-determination.

How did you first learn about popular education?

I first learned about popular education as a child through the activism of my parents. I grew up in a working-class Catholic family in Scotland. I first learned about citizenship activism and standing up for people’s rights and responsibilities going to meetings with my parents.

We grew up organizing through the Catholic church for both cultural survival and resistance. In my family, we had a strong sense of cultural identity and resistance to British domination. Liberation theology was a major influence in the church I grew up in, and the oppression of poor Catholics by British elites was a central concern.

Although we didn’t call it popular education, the Catholic community used the tools of popular education to build community and resistance. Learning to look at life in a political frame was foundational to how we understood ourselves. Our recreational activities were framed by our politics: running summer camps for Catholic youth was political education work. Political learning was immersed in everything we did.

When I went to university, I already had an established commitment to decolonization and anti-poverty activism, but going to school gave me the language to name these politics. I did an internship at Sorbonne University in France in the ’70s and learned about the Theatre of the Oppressed. This gave me a frame to understand popular education and how it fit within movements for social justice.

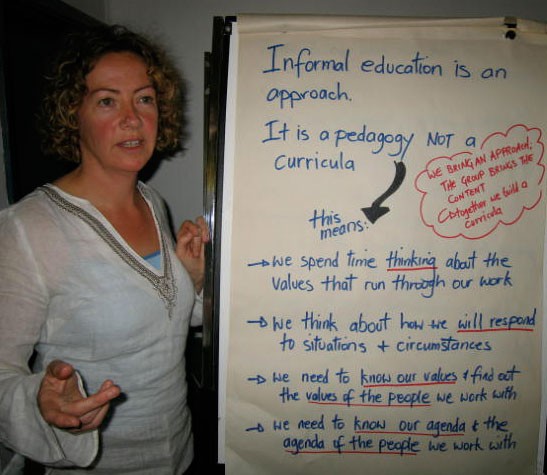

Could you describe the approach of popular education?

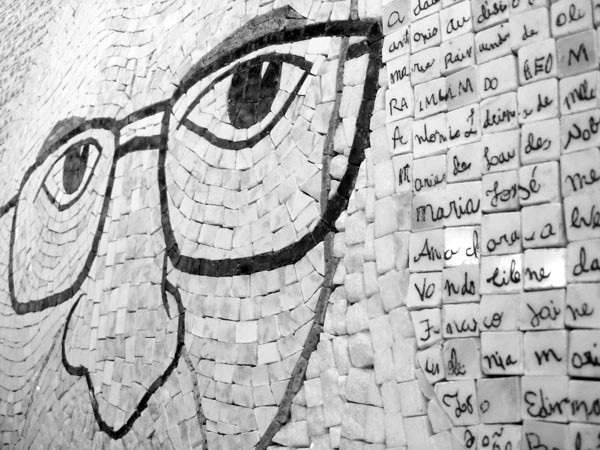

Popular education begins with recognition that the people most affected by issues should be the ones designing the solutions. Many of the formative thinkers in popular education were influenced by liberation theology and an analysis of colonialism. Working to help Brazilian adults read and write, Paulo Freire recognized that teaching was not something teachers do to students but part of a co-operative practice in which both teachers and students learn together. As Freire expressed it, the oppressed must be our guides to liberation.

It is also important to remember that Freire’s literacy work was political. In Brazil in the 1960s, literacy was a requirement to be able to vote. Teaching people to read and write was a political project, enabling people to vote. Popular education was not just about literacy but a frame for political empowerment. More than providing people with skills, popular education supports people’s political engagement.

Applying these insights to theatre, Augusto Boal developed the Theatre of the Oppressed. Like Freire, Boal first developed his approach in Brazil. But by the ’70s, the Brazilian military regime had forced him into exile, and he ended up relocating to France where he taught at the Sorbonne. Boal led the program I took. He used theatre techniques as a means of constructing political knowledge. The Theatre of the Oppressed works to activate the participants and audience to explore and transform the reality in which they are living.

How did you get involved in popular education in Hazelton in northern British Columbia?

I began working in Hazelton at the Catholic school and came to realize that the school here did not share the liberation theology and popular education frame of my experience and training. After a short stint in the public school system, I came to the conclusion that the transformative frameworks I had been grounded in did not exist within the formal education system here.

I started working with the local community college and then the Gitksan Wet’suwet’en Education Society to create more community-driven education. This led me to doing education work for the Gitxsan chiefs’ office.

In the 1980s, the traditional hereditary chiefs of the Gitxsan and neighbouring Wet’suwet’en launched a court case known as Delgamuukw, claiming title and jurisdiction of their traditional territories. Although the court case did not resolve their claim, it forced the government to recognize them and begin a treaty negotiation process.

With the Gitxsan chiefs’ office, my job was to go with a Gitxsan colleague and organize meetings to explain how the Gitxsan governed their territories through their traditional house groups. I spent hours sitting with chiefs learning about traditional forms of organization and working to translate popular education techniques to a Gitxsan cultural context. For instance, the chiefs would call Galts’ep feasts in each of the Gitxsan communities to explain treaty. Drawing upon Gitxsan processes provided a framework of traditional protocols to approach difficult conversations in the community.

Recognizing that the majority of Gitxsan people are young people, we also began to look at how to link Gitxsan traditions to youth culture. Using experiential education on the land, we helped Gitxsan youth become engaged in their communities. Combining Gitxsan politics with popular culture, we also created new ways for youth to express their Gitxsan identity through art and fashion.

Through my work, I began to learn more about the meaning of popular education. Doing popular education involves observing the natural ways that communities learn and teach and validating those ways of learning. This not only allows communities to engage in difficult learning but serves as a vital means of cultivating citizenship. It provides an opening to articulate the rights and responsibilities of community members.

How did you link your work around Gitxsan self-determination to a broader conversation about regional self-determination?

One of the major barriers facing the Gitxsan was government’s lack of willingness to consider alternative possibilities to the prevailing model of development and governance. Government policy privileged large-scale resource development led by multinational corporations. The institutional structure did not have the necessary adaptability or flexibility to incorporate recognition of Gitxsan governance and the territorial rights and responsibilities that Gitxsan people hold.

There was a desire to create an enabling environment for regional self-determination. This meant we needed to bring Gitxsan people together with settlers to build a respectful interface between their different cultural systems. On this basis, we hoped to develop cross-cultural connections in the community and press for a change in government policy.

In the mid-’90s, based on the success of our work among the Gitxsan, the chiefs encouraged a group of us who had been doing popular education to engage with non-Gitxsan people. We formed the Storytellers’ Foundation to support local people self-determining in culturally diverse ways.

What kind of approach did you use at Storytellers’?

At Storytellers’, we focused on how learning can facilitate building active and engaged citizens. When we approached literacy, we understood literacy as an essential tool for people, but in the political Freirean sense. Literacy is not just a skill. It is an awareness of your world and a political engagement. Literacy education for us is about making sure that people have the tools to control their own lives and that communities are empowered to determine their own future.

How has your work with Storytellers’ evolved over the years?

The work evolves because the work is organic. We have had an active praxis, constantly reflecting on our work and being involved in research activities. This has continually deepened our understanding of citizenship and the community.

Our work responds to different moments in the community’s life. And the community continually changes because of shifting internal dynamics and also external pressures. But the central aspect of our work has always remained building the capacities of individuals so they are empowered to control the decisions that affect them.

With the closure of the local forestry mills, we have worked on building resiliency to industrial restructuring. With climate change, we have worked to increase sustainability and adaptability. Through listening to local people, we have learned about the close links between food and citizenship. We did not start doing work with food, but as we learned more about people’s connections to local foods, we began to recognize its centrality to regional citizenship and self-determination.

How do you continue to link your work to popular education and social justice campaigns in other places?

Over the years we have had different projects often involving research, training, or advocacy that connect us to allies. But we do not limit our connections to a project. We sustain relationships over time to build links of solidarity.

We continue to share resources, stories, and people – we do learning exchanges – and this helps us continue to learn about alternative economic models and processes for community development. For instance, we have been linking people in our region with Bolivian activists, sharing experiences and building a network of social solidarity.

What do you see as the relevance of popular education today in both the North and more broadly in the world?

Nothing emphasizes the need for popular education more than the concerted conservative attack on communities today. Years ago we were concerned about how the globalization of an individualistic consumer culture would destroy our understanding of our rights and responsibilities as citizens. Now this has happened. It is visible in the shift to educating people as consumers rather than citizens.

We need community spaces now more than ever. For democracy to be meaningful, we need to reclaim what it is to be citizens. We need to talk about our rights and responsibilities. We need popular education.