At a public meeting in December 2013, Pinehouse Mayor Mike Natomagan offered this capsule history of the Village’s business development corporation, Pinehouse Business North (PBN), and the kind of leadership his administration had provided for its management:

“But as far as how our business is run, we tried very hard as to what we can do – the five of us [PBN board in 2007] – but we knew, sort of, we had an idea about business. We were supposed to save money, but we didn’t. . . It’s no secret what we went through as PBN with the growing pains. We thought we had an idea how to run a business, but we didn’t. Until Revenue Canada came after us and the bank froze our account. We couldn’t really do anything. But at the same time, when I say that, we approached Cameco – we told them we wanted to do it right because we knew how much we needed PBN – to get somebody to help us out.”

While the mayor admitted PBN’s financial affairs had been poorly handled and acknowledged that this was “no secret,” it is doubtful that the townsfolk truly appreciated the magnitude. After delving into the 100 per cent village-owned corporation’s financial status through several Freedom of Information (FOI) requests, Briarpatch magazine has come to only a partial understanding of how dire PBN’s business had at times become. But we do have a sufficient grasp of the situation to know that serious questions still need to be asked: questions about business practices, about leadership, about ethics. Why are they all so hard to answer?

Located about 500 kilometers north of Saskatoon, Pinehouse has not really factored into the history of the province, or even the region, until recent times. A major turning point in the development of Pinehouse came with the completion of an all-weather road from the south in 1979 and the further construction of a road up to Cameco’s Key Lake uranium mine, which began operations in 1983. Over that time, the population has slowly grown from about 700 to 1400. It is a young community – more than 70 per cent under the age of 40. With an unemployment rate hovering around 20 per cent, approximately 60 people are employed at the Cameco mines (Key Lake and MacArthur River). Most of the population has First Nations or Métis background; in the 2011 census, two-thirds stated Cree is their mother tongue.

“Pinehouse Business North Development Corporation” was originally established as a village-owned development corporation under the Saskatchewan Northern Municipalities Act in the early 1990s. It was hoped PBN could introduce the community to some of the economic spin-off benefits associated with its proximity to the Key Lake uranium mine. But those expectations never really materialized. PBN struggled, foundered and was struck off the Saskatchewan corporations register in 1996. In 1998, it was reconstituted as “Pinehouse Business North Development Inc.” Then most recently in 2012, following a share-split, “Pinehouse Business North Limited Partnership” was established, taking over operations from PBN Development Inc.

Most of the labour service contracts signed by PBN (in its various manifestations) over the past decade have related to the uranium/nuclear sector. Between 2005 and 2012, PBN brought in over $26 million in revenue, yet it has had a mediocre record of translating that revenue into community dividends. Through FOI requests, Briarpatch magazine was able to obtain financial statements for just three years: 2007, 2008, and 2012. PBN and the Village claim that no financial statements were created for 2009 to 2011, a period when the corporation grossed over $13 million. What is more, no financial statements for 2013 or 2014 have been made available for public scrutiny as yet.

As a sidebar to this story, it should be noted that when the Village administration initially denied access to the PBN records requested, Briarpatch submitted a Request for Review to the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner (OIPC). Upon the OIPC’s urging, a few relevant documents were retrieved, but the Information Commissioner in his report of November 2015 has accepted that the Village administration had made a “reasonable search” to find more records and was unable to do so. No questions concerning why recent public documents (all of them less than seven years old) had disappeared seem to have been asked.

In 2006, PBN was for all intents and purposes non-functional. But in 2007, a new business plan was developed. Local businessman John Smerek was asked to provide his expertise as a consultant. By the end of that year, contracts amounting to $888,683 had been secured, primarily as general labour services for Cameco’s Key Lake mine. But Smerek had already terminated his business relationship with PBN in August when he learned that the Village council had decided to appoint several of their own councilors to the PBN board. The new board had promptly begun paying themselves generous stipends for those positions. Smerek saw this as putting the community leaders in a conflict of interest, and this is what caused him to withdraw his services. For the remainder of 2007, the board received $80,924, and in 2008 that grew to $210,894 in remuneration.

Already in 2009, PBN had lost $294,848, despite bringing in over $3.5 million in revenue that year. Through the few documents concerning this problem received from the Village as a result of FOI requests, we have deduced that this is the same year that Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) intervened for non-payment of the Goods and Service Tax, amounting to $211,000, and had PBN’s banking institution freeze its account. The Village and PBN claim that after a careful search they cannot find the records to corroborate this. And according to the Information Commissioner’s report, “Further complicating the search is that it was unclear as to the year the accounts were frozen due to the continuance of payment of source deductions.”

Apparently no one in the Village or PBN administrations can recall the exact date all this happened, even though several officials at the time are still serving in public capacities in Pinehouse, including current Mayor Mike Natomagan, Councilor Greg Ross, and Corporate Engagement Officer Vince Natomagan. But then again, memories among Pinehouse politicos can be short. Answering a question from Eagle Feather News last year about difficulties with responding to previous FOI requests from Briarpatch, Mayor Mike said, “The things they are asking for are ridiculous. For example they want every email and phone call I have received from Cameco since 2007. I have trouble finding emails from last week.”

In an attempt to explain the lack of documentation in this regard, the Village administration has indicated “the Village and PBN were not separate entities during this timeline [2009–2011].” They claim that PBN’s finances were managed through a sub-account in the Village’s bank account over those years. It was “money in/money out.” But the Village’s audited financial statements do not support that assertion. For example, PBN’s contract revenue in 2009 was $3,537,244, yet the Village statement indicates the total revenue for the Village that year was just $1,539,864. When the Village’s auditor was questioned about the discrepancy, he was unable to verify the Village’s claim.

It’s not difficult to see why the Village council and PBN’s board of directors (they were virtually the same people) decided that a restructuring was necessary if PBN was to survive. Its contractual relationships with Cameco and other partnerships were in serious jeopardy. Consequently, in December 2010, the Village council approved a new business charter, with a mission statement that emphasized its commitment “to uphold best practices to administer our business ventures in an accountable, professional and transparent manner.” The charter indicated that a new board would be appointed comprising a maximum of two members of Village council, one member from the Kineepik Métis local, one Pinehouse resident at large, and three independent directors. The charter also committed the new board to producing audited financial statements within six months of the end of each fiscal year, quarterly financial and operational reports to the Mayor and Council, and through Council in turn quarterly reports to the citizens of Pinehouse.

The new PBN board was named in 2011, and in 2012 Bruce Richet was appointed to replace (Deputy Mayor) Greg Ross as CEO. Richet was a consulting engineer who remained in the position less than one year. Also in 2012, the Pinehouse Village Council and Pinehouse Business North Development Inc. agreed to a share-split whereby Pinehouse Business North Limited Partnership was created. PBN Development Inc., while still a corporate entity, ceased to be active. PBN Limited Partnership became the operational corporation. Julie Ann Wriston, a former PBN employee and MBA student at Cape Breton University, became CEO in December 2012. She explained at a community meeting in December 2013 that the new corporation was established to protect the Village in the event of PBN going bankrupt. It was not immediately apparent how the Limited Partnership regime would provide any more bankruptcy protection than would be the case with PBN Development Inc. In essence, the share-split allows PBN Limited Partnership to bring in other project-driven corporate partners who can help capitalize very large contracts, although to date this doesn’t seem to have occurred.

Whatever the intentions of those involved, it is hard to see how PBN has become any more transparent or accountable to the community. According to the mission statement on its website, PBN remains committed to “being open, fair and transparent at all levels and with all people.” And Julie Ann Wriston, the former CEO who left the corporation in December 2014, is insistent in her philosophy that communication is key to community and corporate governance. In an online video entitled Visioning the Initiative, Orchestrating the Transformation she recalls her tenure at PBN: “My intention [as CEO] was to be there, to be open, to speak to whoever wanted to speak to me. As well, we did quarterly large community meetings … so anybody with questions was definitely encouraged to ask that of me and of the corporation.”

But these rosy statements do not match the reality in Pinehouse, and they are especially perplexing to anyone outside the small nexus of power in the village. Nobody interviewed by Briarpatch could recall any quarterly meeting, at either Village Council or in the community hall, where full operational and financial information on PBN’s activities has been provided. There has been no CEO at Pinehouse since December 2014. There have been no financial statements released – only what was provided to Briarpatch through its FOI requests, and even those are incomplete. Pointed questions regarding PBN finances and operations at public meetings are routinely deflected or disregarded.

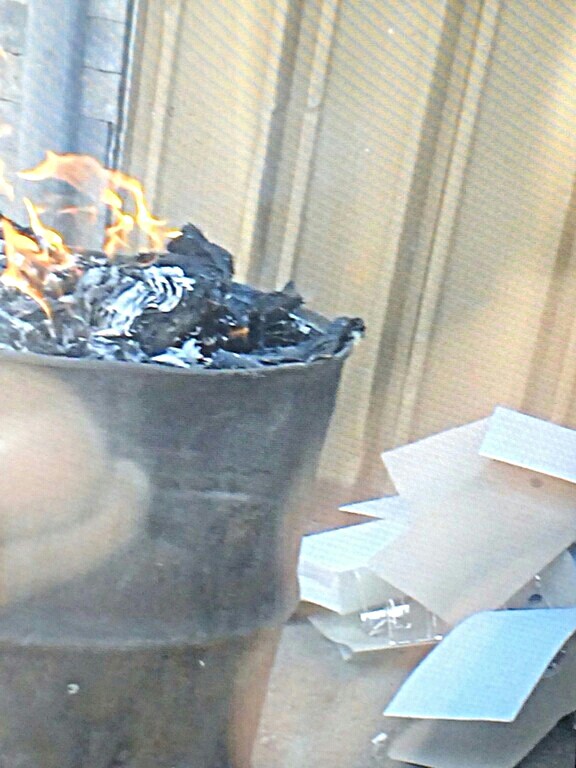

There is a legal requirement to keep business records for a minimum of six years (i.e. since the end of 2008), but the Village has either lost, misplaced, or destroyed the bulk of PBN’s corporate memory bank. Yet this seems to be of little concern to the Village, to PBN itself, or to Saskatchewan’s current Information and Privacy Commissioner. The Village Administrator and her staff were seen destroying multiple boxes of documents in burning barrels outside the Village office on June 23, 2015. Although there is no indication that the documents Briarpatch was seeking access to at the time were burned, the fact this incident occurred while an FOI request was pending (and later denied) raises concerns.

Pinehouse Business North, a publicly owned corporation, has evaded minimum legal standards of accountability, and this ought to worry the local electors, provincial overseers of municipal affairs, and all those who believe that democracy cannot function without transparency from elected leaders and public organizations. The inconsistencies and incongruities that Pinehouse officials have been permitted to trade in lieu of basic legal requirements for recordkeeping and public disclosure undermine the free exercise of democratic governance in Pinehouse and, by example, in all other local authorities in the province.