It was midnight on October 25, 2012 when Hurricane Sandy penetrated the Sierra Maestra mountain range and roared toward Santiago de Cuba, the second largest city in Cuba. The winds raged at over 200 kilometres per hour, uprooting and devouring everything in their wake: agricultural crops, fruit trees, buildings, and homes. Celia Soca and her husband woke suddenly when a massive mango tree came crashing through their roof. In the next room, her children wailed. Soca knew they had to leave fast and head for higher ground.

“The night before, we heard about the cyclone warnings, but we couldn’t have predicted that Sandy would be so bad,” recalls Soca, a 39-year-old farmer. “My husband got the kids to an emergency shelter first, then came back for my mother and father.”

Soca was the last to leave her family’s farm, a 70-year-old property located on the outskirts of Santiago de Cuba. The family-owned land had deep sentimental value. It also generated the family’s income. But Soca had to flee into the mountains during the storm, while fearing what would happen to her cattle, pigs, and fields of banana and animal fodder.

The eye of the hurricane struck the coastline with waves reaching nine metres. The coasts were flooded and the water surged inland. Hurricane Sandy raged for six hours. When people emerged from shelters and refuges, the city streets were blocked with small mountains of rubble. The hurricane destroyed nearly half of Santiago’s public and private infrastructure, damaging over 170,000 homes. Surrounding the city, the hurricane swallowed up agricultural production, tearing down 26 square kilometres of bananas, destroying pig and poultry farms, and decimating coffee plantations. Processing facilities, grocery stores, and health-care facilities were severely damaged. Total losses in Cuba reached over US$2 billion, making Sandy one of the costliest hurricanes in Cuban history. Soca and her family lost everything.

“It was a psychological nightmare,” she says. “It took us months to recuperate.”

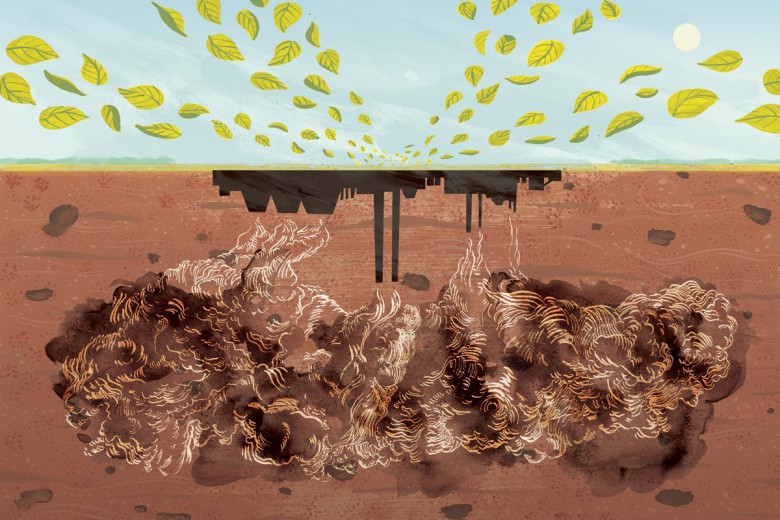

But the disaster didn’t immobilize Soca. She picked up the pieces and rebuilt what her family had lost. The Cuban government offered a loan program to help the hurricane-affected residents in Santiago re-establish their homes. It also subsidized the cost of construction materials to ease the burden of rebuilding. A Credit and Services Co-operative (CCS), a state-sponsored credit co-operative for Cuban farmers, provided additional support; Soca was able to access funding to reconstruct a milking barn, and buy a new herd of cattle and several pigs for breeding. Soca attended an educational workshop on permaculture, a holistic strategy for growing sustainable food, fibre, and fuel, and began to redesign the layout of her farm to increase its productivity, diversity, and resilience against flooding and drought. The course was organized by a local church community to help guide recovery efforts after the hurricane. She emerged from the workshop aiming to grow a wider variety of fruits and vegetables closer to her home, enabling her to increase her family’s food security.

Soca was just one of the thousands of Cuban women who played important roles in responding to the devastation that Hurricane Sandy left behind. In Santiago de Cuba, women were directly involved in the recovery work: they applied for government resources, distributed food and clothes, and collectively rebuilt their neighbourhoods and communities. According to the UNDP’s report on Gender and Disasters, women’s participation in different stages of disaster management – prevention, mitigation, response, and recovery – is critical to helping countries overcome disaster events.

However, a gender-equitable response isn’t always applied in countries of the Global South, where the UN reports that women are 14 times more likely than men to die in a disaster. In the aftermath of catastrophic weather events, girls and women face risks related to sexual assault, rape, and abuse as a result of civil chaos and lawlessness. After the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, women living in displaced-person camps were 20 times more likely to report a sexual assault than women living in their homes.

Despite the fact that Haiti and Cuba are neighbouring island nations in the Caribbean, they’ve experienced drastically different outcomes from natural disasters. Hurricane Sandy didn’t directly strike Haiti in 2012, but the indirect storm caused massive inland flooding, killing 54 people – the highest reported death toll of any country impacted – as well as ruining agricultural crops and causing massive food shortages.

A recent study in Ecology and Society by Adelheid Pichler and Erich Striessnig compares how access to formal education impacts the outcome of disaster management in Cuba, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. While the countries share the same levels of geographical risk and vulnerability to hurricanes, they differ vastly in how they are affected. For example, eight years prior to Hurricane Sandy, Hurricane Jeanne claimed more than 2,700 lives in Haiti and 20 lives in the Dominican Republic. But despite the severity of the disaster, no lives were lost in Cuba. The study argues that access to education – with particular emphasis on women’s access to formal education and practical, skills-based education – determines how countries are able to prepare for and respond to disaster crises. Gender-equitable education is critical to help men and women know what to do when a disaster strikes: evacuate their homes and seek shelter in established emergency centres.

Today Cuba is leading the way in gender-equitable education in Latin America, though it wasn’t always that way. Before the Cuban Revolution in 1959, even though Cuba was considered one of the most prosperous countries in Latin America, women’s participation in the formal economy was staggeringly low: they constituted only five per cent of university graduates and 12 per cent of the workforce. The revolution set out to directly address gender inequality through policy and legislation. Fidel Castro called it a “revolution within a revolution.” Today, the literacy rate is 100 per cent among 15- to 24-year-olds. Women make up the majority of high-school and college graduates, nearly half of the island’s workforce, and nearly half of Cuba’s National Assembly. In the 2014 World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report, Cuba ranked high regarding women’s status, placing 18th among 142 nations in women’s political empowerment. The formal mechanisms of education have resulted in strong indicators of equality, although informal gender dynamics and persistent machismo are still barriers to equal power-sharing in all realms of life.

Conversely, the literacy rate in the Dominican Republic is 10 per cent lower than in Cuba and access to disaster preparedness education is severely inadequate. While girls reportedly outnumber boys graduating from high school, the challenge in the Dominican Republic isn’t only access to education, but access to quality education. This gap has, in part, resulted in fewer women in the labour force. The rate of unemployment in the Dominican Republic is disproportionately higher among women than men. Women face greater challenges to daily living, including the risk of domestic violence and machismo (sexist attitudes), poverty, and higher rates of HIV/AIDS. In the event of a disaster, women’s risk of facing impoverishment, violence, or death is greater. Many women refuse to evacuate their homes for a number of reasons – lack of access to education, poor early warning of disasters, sparse government emergency shelters, and practically no support in their recovery efforts. The demonstrated lack of state support inflames the threat of looting and violence, which can further discourage evacuations. Women may feel that they and their belongings will be marginally safer if they stay. It is clear that state-based responses, or non-responses, to weather disasters are couched in larger responses, or non-responses, to gendered social inequalities.

During a 2012 flood in the Dominican Republic, one woman climbed onto her roof. She explained to researchers, “I always stay there. It doesn’t matter how high the water rises. Anyone has to stand watch, otherwise everything will be gone. Gangs will arrive and take from wherever they can.” The civil chaos that tends to follow disasters, particularly in countries of the Global South, leaves women at risk of physical and sexual assault. Women also reported that they didn’t feel safe in the few government safety shelters, where the dormitories and toilet facilities weren’t separated by gender.

The study also suggests that women’s capacity to participate in disaster management is dependent on their access to health-care services. In Cuba, where family doctors reside and practise at the neighbourhood level, women have one of the lowest maternal mortality rates in Latin America and among all Global South countries. In Haiti, where only 30 per cent of women give birth with the assistance of a skilled medical professional, the maternal mortality rate is 380 deaths per 100,000 live births, one of the highest rates in the world. Women in Haiti and the Dominican Republic also often report that, following disasters, they face increased rates of diarrhea, fever, and cholera – preventable diseases that have been practically eradicated in Cuba due to public health education, vaccination, and home fumigation campaigns.

“Without being a prosperous country, Cuba has found purposeful interventions to cope with natural disasters,” write Pichler and Striessnig. “Looking into the future, Cuban society seems astoundingly resilient with respect to the expected climate change and should be considered a blueprint for the entire region.”

The nation’s resilience in the face of climate change disasters is the result of the work of the people. Nilda Iglesias, a 48-year-old mathematics professor and doctoral candidate living in Santiago de Cuba, was left homeless with her family in the wake of Hurricane Sandy.

“After Sandy, we lived in an old pig house,” says Iglesias. “We lost furniture. It left us without clothes and shoes. It destroyed our banana plantation. We touched rock bottom.”

Gradually, Iglesias began to rebuild her family’s house. Shortly after the hurricane, Iglesias, like Soca, attended an educational workshop on permaculture and learned to plant food closer to home. Today, Iglesias has an abundant permaculture garden with more than 30 varieties of vegetables, fruits, and medicinal plants. Iglesias is also experimenting with food security in the kitchen. She processes fruits and vegetables from the garden to make sauces, jams and jellies, vinegars, juice, and dried fruits. In her garden, nothing is wasted. She uses the peels of fruit to make vinegar and harvests fallen fruit, often bruised, to dry in the sun.

“I’m teaching people how to preserve what they grow, so when they don’t have fresh fruits and vegetables they can still access the nutritious food that they need,” says Iglesias.

Living through the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy has taught Iglesias the importance of building resilient systems and striving for food sovereignty. She continues to teach mathematics at the university in Santiago de Cuba and work on her doctoral thesis, but she dedicates time in the evenings and on the weekends to growing food for her family. Above the entrance to her garden hangs a sign that reads EL RENACE – “The Rebirth.”

“It’s allowed my family to move forward and recuperate from the hurricane,” Iglesias says passionately. “The garden has made us revolver a la vida – ‘to return to life again.’”

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)