About 1,000 people – patient, if excited – form a damp line that loops down a hallway, hangs a right, traces a big “U” around the foyer and snakes off around one of the building’s curved walls.

Name-tagged marshals – some barely out of their teens – are just as excited as the crowd. The name on everyone’s lips? Judith Butler.

The renowned queer theorist is in town to deliver a keynote lecture as part of the seventh annual Israeli Apartheid Week in Toronto.

Author and editor of a stack of books, Butler became a household name – at least in geeky, queer households – for Gender Trouble, a 1990 classic of theory in which she argues that gender is performance, rather than part of our essential being.

Butler’s theory of gender-as-performance remains her best-known contribution to academia, but for the last decade her attention has gradually shifted from gender to the politics of war. Now she’s struggling with questions like, whose deaths matter, and why are some deaths grievable but others not?

During a one-on-one with Marcus McCann of Xtra!, a gay and lesbian online newspaper, Butler talks about the challenges facing the gay movement – including its increasing reliance on state recognition as a tool of change – and draws parallels between queer liberation and Palestinian human rights work.

McCann: It seems that in the last decade there has been an uptick in queers who are taking issue with Israeli foreign policy.

Butler: For me, the term queer, from its early days, was an idea of alliance. It wasn’t, for me, an issue of identity. Queer was a way of accepting that there are complex identifications, and that gender and sexuality were not always easily described by identity categories. And I liked what Eve Sedgwick had to say, early on, that anyone who was against homophobia was welcome to the club.

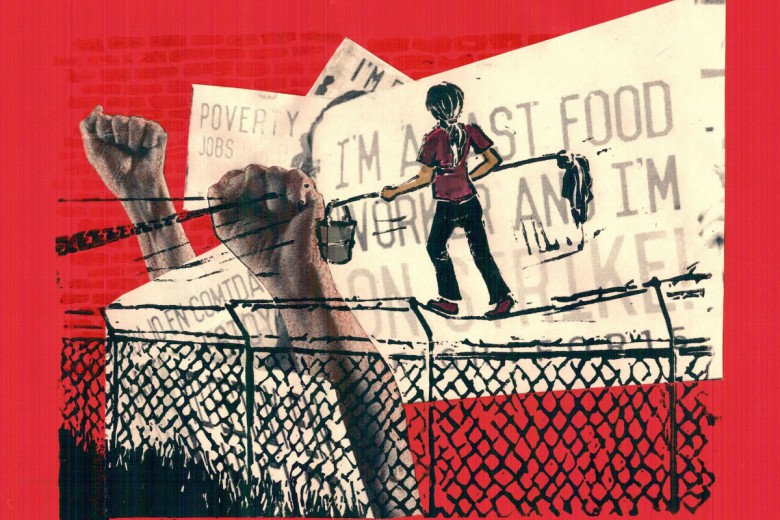

I think, from the early ’90s, [when] there were a number of populations that were suffering in the AIDS crisis in the United States, it was imperative to make alliances across minority populations. And the queer struggle for visibility and for AIDS education and AIDS prevention really started to be involved with questions of economic justice and political equality more broadly.

But, let me just say, it’s not a question of Israel’s foreign policy. Twenty per cent of [Israel’s] population is Palestinian. And they have what I would call damaged rights. They don’t have full equality under the legal structure of Israel. And then the occupied territory has a kind of uncertain status. Is it independent? Is it Israel? Certainly, Israel controls it militarily, and Israel retains the right to accept or reject any elections that take place there. So there’s no political autonomy; that’s what “occupied” means. So it’s not exactly foreign policy. It’s neither domestic nor foreign policy. I don’t know how to describe it.

In your essay on gay marriage in Undoing Gender, you point out that the push for recognition of gay marriage segregates the queer population by rendering illegitimate other types of sexual arrangements that do not adhere to the marriage norm. Also in that essay, you’re trying to defend the movement against homophobes, the people on the right wing who are opposed to gay marriage, without yourself endorsing it. It seems like an uneasy balance you’re trying to stake.

Yeah. Well, I think there are many homophobic arguments against gay marriage that have to be opposed. And then there’s a separate question, which is should gay marriage be at the centre of a movement that is meant to enfranchise or empower sexualities? It’s not at the top of my agenda. And I’m not sure it should be at the top of the agenda.

I think, in the U.S. at least, the right-to-marriage movement has focused on property and wanting acceptance as normalized bourgeois people, and monogamy, and the idea of couplehood. Think about the complex ways in which sexual and intimate relationships take place; they don’t always conform to that. There are modes of sexuality that aren’t centred on marriage-like arrangements, and that’s been part of a radical sexual movement for a really long time, calling into question how we arrange sexuality, and what arrangements are best, and what works and what doesn’t, and what are the norms or ideals around which we organize our sexual lives. It seems really important to keep those questions open.

If that’s true, then the movement around Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell must be even more clearly about state recognition.

Of course, the point of repealing Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell is to make sure that gay and lesbian people can come out in the military and not lose their positions or suffer discrimination or harassment.

Of course I’m against harassment and discrimination and there should be no such policy, but we also need a queer critique of the military. If we’re just going to struggle for the rights of people to be out in the military, then we’re not asking what the military is doing and what we think the military ought to be doing.

It seems to me that queer people know what it is to be dishonoured and not to have their lives considered valuable, not to have the opportunity to publicly grieve the losses we have endured. And that links up with questions of war, really.

My work has shifted, from sexuality and gender to the politics of war, but they’re really linked by the question of whose lives count. And when we think about targeted populations and civilians who lose their lives in America’s wars, I think that queer people should have solidarity with those populations whose lives are not considered livable. That’s a kind of alliance that I would understand as a queer alliance.

So that explains why I would – as someone who elaborated a queer theory – be very concerned with the situation in Palestine, where rights are abrogated and there is no real political self-determination for the Palestinian people, and where violence is waged against Palestinians, and where the loss of those lives is not regarded as equally valuable, as equally lost.

Speaking of bodies that are grievable or not grievable, in Canada, there’s been a bit of a resurgence in anti-prostitution feminism. There was a hotly contested debate here on the University of Toronto campus between the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women and folks from Maggie’s, which is a support and advocacy group by and for sex workers. And in Vancouver, a group of lesbian feminists who just released a statement calling for the abolition of prostitution. I wanted to get your thoughts on why there might be a resurgence right now.

I’m more aware of these debates in the U.K. than I am of the debates in Canada. But I do think that we have to ask whether all prostitution is coerced. I think it’s one thing to be against coerced sexuality — I’m against coerced sexuality, I’m against coercion, I’m against rape — and it’s another thing to decide that prostitution is by definition coercive sexuality. There are many women who enter into sex work who are actually making a living wage and who need greater protection and good medical care and some kind of retirement guarantees. And I think we would be making an error if we understood a movement for those employment conditions as somehow promoting coerced sexuality.

I’m not convinced that all prostitution is coerced. It’s a choice that people make under certain economic conditions. And I can think of a lot of forms of labour that women are in that they may not like very much, that they will wish that they had another set of options, but I’m not sure that prostitution is the worst of them. And I guess I would call it sex work rather than prostitution.

When you decided not to accept the award at the June 2010 Christopher Street Day celebrations [Germany’s Pride festival] in Berlin, you said in your refusal speech that gay and lesbian people were being used as a way to fuel anti-immigration positions in Europe. Can you elaborate on that?

Some of the leaders of that parade espoused very strong anti-immigration positions. They were calling for a greater police monitoring of minority populations in Berlin and seeming to identify the threat of homophobia in Germany as coming from new immigrants. It struck me as Islamophobic, and of course, wasn’t considering the ways in which homophobia is reproduced at various major German institutions – educational institutions, religious institutions.

Not to say that there aren’t immigrants who have strong views about homosexuality or even have been offensive in their approach to homosexuality or gay people. But there is also a very large queer community of colour in Berlin, and they were acting as if queers were white and their enemies were not. So, I couldn’t really accept that map of power.

I think we need to be in alliances that are dedicated to broader goals of social justice. I don’t think we should be taking our freedom at the expense of others.

A longer version of this interview was originally published by Xtra! at www.xtra.ca.