On September 26, after 148 days of striking, the negotiating committee of the Writers Guild of America (WGA) announced to their members that they’d reached a deal with studio executives. “[T]his deal is exceptional,” they declared. In addition to the usual demands like increased pay and better benefits, members were also demanding larger writing teams, longer contracts, and better residuals (which are similar to royalties). Arguably, the biggest win was worker protections surrounding artificial intelligence (AI).

As Paris Marx writes in this issue, we’ve been bombarded all year with headlines about how AI will put everyone out of work: truck drivers will be replaced with self-driving cars, artists with AI-generated art, and writers with ChatGPT. The use of AI was one of the main motivators for writers to strike in the first place: studios made it clear they intended to use AI to write scripts and possibly replace writers.

But writers fought for – and won – the right to control AI’s use in productions. Writers and productions can use AI technologies if they want to, but studio executives can’t require them to use AI, nor can they use the technology to reduce or eliminate writers and their pay. The WGA’s deal is one of the first to include language outlining the use of AI, but as the tech industry keeps searching for ways to make their expensive AI investments profitable, it’s sure not to be the last.

At Google’s annual I/O developer conference in May, CEO Sundar Pichai announced the company’s commitment to “building and deploying AI responsibly so that everyone can benefit equally,” before sharing some of the company’s newest AI tech innovations. Pichai’s list, however, omits the AI product the company says will supposedly help newsrooms: a personal assistant for journalists known internally as Genesis.

Genesis “can take in information – details of current events, for example – and generate news content,” anonymous sources told the New York Times. The tool is being developed “[i]n partnership with news publishers, especially smaller publishers” to “help journalists with their work” a Google spokesperson wrote in a statement to The Verge.

Though Genesis is still being developed, Google has already pitched it to media execs at the Times, Washington Post, and News Corp (the owner of the Wall Street Journal). Several outlets are already encouraging their staff to use AI to help with tasks like scanning content, picking images to pair with stories, and writing articles. Outlets like Buzzfeed and Gizmodo have published articles written by AI. However, the hazards of AI-generated news content have already made themselves apparent. In August, Microsoft Travel published a widely mocked AI-written travel guide for Ottawa that listed the city’s food bank as a “cannot miss attraction” and recommended that readers “go there on an empty stomach.” The company claims the article was not published because of “unsupervised AI” but “human error” in reviewing the article.

As Marx explains in his article, technology doesn’t take our jobs. Instead, it helps bosses increase worker surveillance and turn well-paid, stable jobs into poorly-paid, precarious ones. As a spokesperson for Google told The Verge, the technology isn’t meant to replace journalists, but to “[enhance] their work and productivity.” In other words, AI will increase journalists’ pace of work and output without increasing their wages or benefits to compensate.

Meanwhile, many of the workers behind these products are poorly paid and lack many basic labour protections. As Véronique Sioufi reports in our cover story, hundreds of Canadian workers are training new AI technologies while making as little as a penny per assignment.

When we were discussing the article, Sioufi explained to me that many of the workers didn’t even consider it work because it was so unpredictable and poorly paid. The assignments, they told her, are a way to make a bit of money during their spare time, even though for some workers it has become their main source of income.

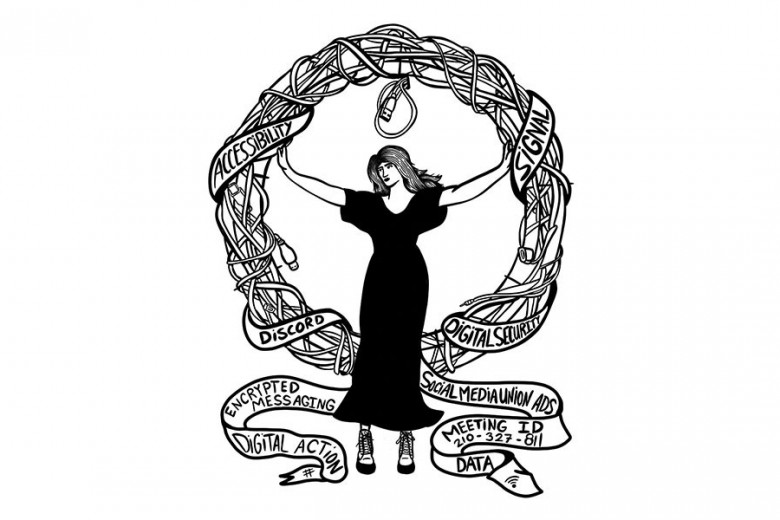

Canadian unions have struggled in recent years to meet the needs of the workers they represent. They’ve failed to keep workers safe from the dangers of COVID-19, to invest in organizing migrant workers and gig workers, and to show international solidarity with the BDS movement. With the stakes (and rent) already too high for low-wage workers to wait for Canadian unions to invest in organizing, the labour movement has to be willing to actually face today’s many real challenges if it hopes to reverse forty years of declining membership and waning strength.

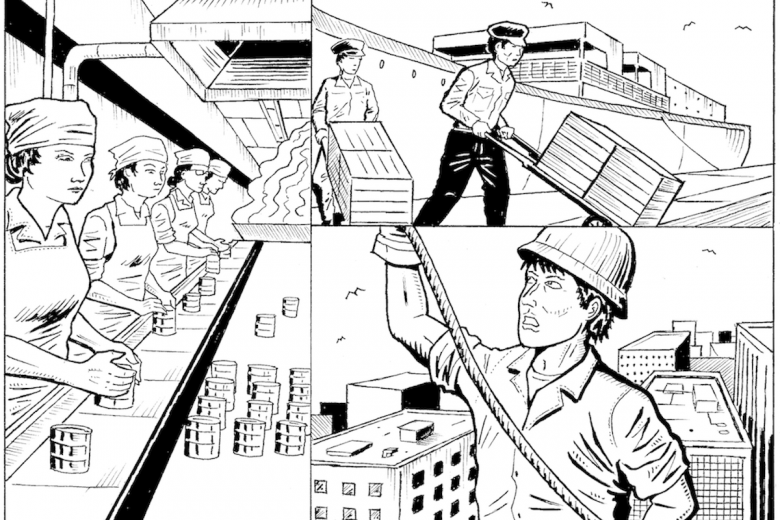

This issue is full of stories where organizers have strategized and mobilized both in and outside of unions to try and face those challenges, and in these cases we can see the ambition, commitment, and solidarity necessary to find a way forward for the labour movement. Paige Galette shares strategies she and her comrades are using to unionize and demand status for migrant workers in the Yukon. Adam D.K. King writes about the scale of organizing necessary to take on giants like Starbucks. Phoebe Fuller reports on B.C. organizers’ fight for protections for workers from extreme weather. And Megan Linton, Mary Jean Hande, and Ethel Tungohan map out a future of care systems that treat migrant care workers and disabled care receivers with respect. As bosses and Big Tech push us to make every second productive, this issue’s articles show that we can take control of working conditions, from status for all, to a just transition, to Big Tech’s reach, if we’re willing to make those demands – and to act for them.

_1200_675_90_s_c1_.jpg)