One year after the student strikes and Maple Spring that erupted in Quebec in 2012, the ongoing wave of social protests is having to recalibrate itself to meet a new set of challenges.

Former Liberal premier Jean Charest incited popular outrage with a proposed university tuition hike and broader austerity measures, but with last September’s election of Parti Québécois (PQ) leader Pauline Marois, many are finding that the neoliberal policies of the Charest government are only taking on slightly subtler forms. In late February, Marois held a two-day summit on post-secondary education and announced that her government would continue to increase tuition costs, much to the chagrin of the student movement.

Also continuing is the northern Quebec development project known as Plan Nord under the previous provincial government and recently rebranded Le Nord Pour Tous under Marois. According to its official website, Plan Nord is a 25-year project estimated to bring in $80 billion in investments and create 20,000 jobs in mining, forestry, and dam projects. On February 9, 36 people were arrested at protests outside a trade fair on natural resource industries in Montreal, where demonstrators chanted “Charest, Marois, même combat!” (“Charest, Marois, the same fight!”) and decried what they saw as the same colonial development plan with a new name.

Several Innu communities of Nitassinan, the name for the traditional Innu territory of northeastern Quebec and Labrador, have for years been engaged in a heated struggle against Plan Nord. On January 1, Jeannette Pilot, an Innu grandmother and long-time activist for the defence of Nitassinan, began a hunger strike. She was joined by Aniesh Vollant, an Innu youth from the Uashat reserve on the north shore of the St. Lawrence Seaway, in eating only fish broth, a cultural symbol for hardship, sacrifice, and strength for many nations, according to Indigenous scholar Leanne Simpson. Their action was directly inspired by Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence and the Idle No More movement. Vollant continued her hunger strike for 43 days, and Pilot, 82 days.

Asked why she decided to take up a hunger strike, Pilot weaves together many different issues of different scopes. Like many in the Idle No More movement, she wants Bill C-45 abolished. But she also wants an end to Plan Nord and an autonomous government for the Innu.

“Right now, Indigenous people all across the country are rising up and demanding that the government recognize their autonomy,” says Pilot, her voice noticeably weakened from her hunger strike.

Pilot’s struggle began long before Idle No More took off. In 1992 she was arrested for protesting the SM-3 dam near Sept-Îles. In 2012, she marched over 900 kilometres from Uashat Mak Mani-Utenam to Montreal to protest Plan Nord.

The Innu have never signed a treaty with the Canadian or Quebec governments, although one is currently being negotiated with the Innu band councils. Pilot sees the Idle No More movement as a way to open up the dialogue for Innu self-determination, rather than a treaty.

“The Idle No More movement has really touched me personally, and others in our territory as well. This is why we are demanding self-government,” says Pilot. “Now is the time to manage ourselves, to make our own laws, and to cut the ties with the federal and provincial governments.”

For Pilot, Plan Nord is a direct threat to Innu culture and way of life.

“We have our medicines up there, our hunting, our animals, our rivers – everything is there for us. What is in the forest is anchored in our souls. If it is destroyed, it will really be a total assimilation for us.”

Conflicting expectations

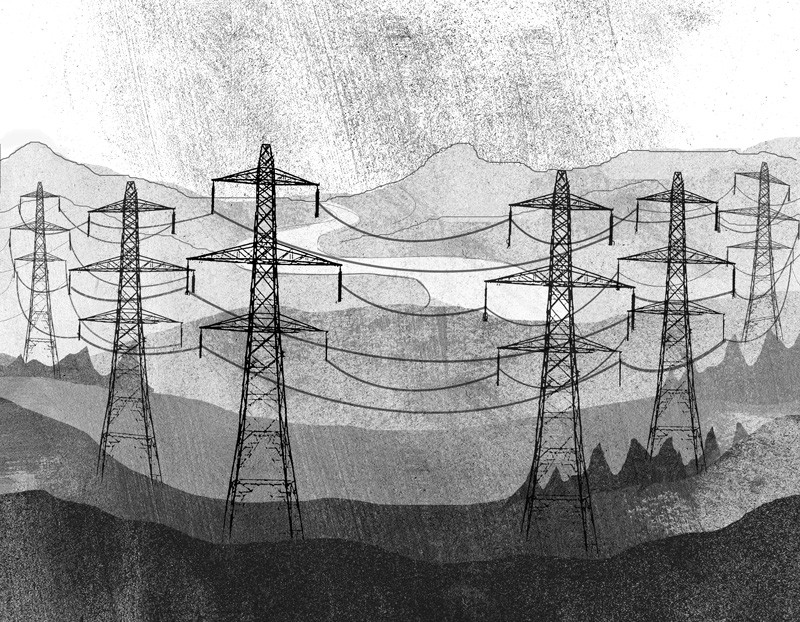

One of the main points of concern for the Innu with Plan Nord is the Romaine River dam project. The Romaine is a 500-kilometre-long river that runs south from the Quebec-Labrador border and empties into the St. Lawrence. The area is home to woodland caribou, black bears, wolverines, and other large mammals. The river, one of the last undammed rivers in Quebec, teems with salmon, eels, and many other species of fish. Hydro-Québec is hoping to complete a series of four large dams along the Romaine by 2020, which would generate a total annual output of eight terawatt hours, or the average energy used by 450,000 Quebec households.

Many Innu activists have protested the Romaine dams not only because of the threat to biodiversity, but also because large swaths of forest will have to be destroyed to make way for the high-tension lines to transport electricity from the dams to consumers in Montreal and other cities.

Gary Sutherland, a spokesperson for Hydro-Québec, says that, despite opposition, the Crown corporation does try to get the support of Indigenous communities.

“One of the main concerns of Hydro-Québec is that our projects are well received by the local communities. So we work hard with those communities to establish partnership agreements with them,” says Sutherland. “We know there are going to be conflicting expectations sometimes. We take the necessary steps to make sure that those host communities, including the Aboriginal communities, are involved both in the development and benefit from the economic spinoffs at all stages of the project.”

Hydro-Québec held two referendums in 2011, one in the Uashat reserve and another in Uashat Mak Mani-Utenam, asking if communities would allow transmission lines from the dams to be built across their territory. Neither received majority approval.

“A huge, dirty project”

Chris Scott is a Montreal-based environmental activist with l’Alliance Romaine, a coalition devoted to protecting the Romaine river against Hydro-Québec’s dams. Scott has travelled the length of the river on a few occasions to observe the impacts of development now underway.

“It’s a huge, dirty project,” says Scott. “It will drain the river, flood huge amounts of boreal forest, and force the river out of its normal course into an underground tunnel.”

Another point of controversy is the amount of public subsidies going into the development relative to the royalties coming out.

“Previously, under governments like [Maurice] Duplessis’, companies would have to pay for their own access to these territories,” explains Scott. “They would build their own road, and if the road was clearly serving the company to get into a mining site and take the minerals out, the company would pay for that road. That was the old approach. The new approach says ‘we need to encourage these companies to take our minerals for almost nothing.’ So they pay very low royalties.”

According to Scott, the Quebec government is paying for industrial development roads in the areas around Natashquan and Chibougamau that were previously untouched by large-scale development. He says that the government is also furnishing the electricity that companies need to conduct their mining and smelting operations.

Fighting to be heard

On an official trade mission to New York City in December 2012, Marois reiterated her support for development in Quebec’s north but underscored that she wanted to do it differently than her predecessor. In an interview with the business news website Bloomberg.com, she stated that “We [the Quebec government] want to raise more revenues from royalties, but we don’t want to kill the industry.” The provincial government is hoping to bring in new mining legislation that would set a five per cent minimum royalty on minerals extracted from the ground in addition to a 30 per cent tax on “super profits” from the extraction of non-renewable resources.

Regardless of the amount that mining companies will pay in royalties, or the referendums with Hydro-Québec, the impact of ongoing mining and dam projects on the land will be severe, according to many Indigenous people and environmental activists. As Scott says, “I’ve seen month by month, week by week, the deforestation taking place. There will essentially be nothing left of the natural ecosystem when this is finished.”

While environmental activists in Montreal are busy strategizing, the Innu in northern Quebec are living the consequences of development that is pushing ahead unhindered. Few have faith that Marois will offer anything significantly different from Charest in terms of environmental protection.

“Nothing has changed; they just changed the name to make it seem nicer,” says Mathieu Morin-Robertson, an Innu man originally from the Lac Saint-Jean area in central Quebec. “The projects are continuing, regardless. Whether it’s the Liberals or the PQ, we need to keep fighting to be heard.”

For her part, Jeannette Pilot has made it clear that she sees her hunger strike in the context of a larger struggle that extends beyond Native reserves and territories. “We’re doing this just as much for non-Native people, because Mother Earth is in danger,” she says. “We will continue until the government recognizes that we exist, because right now we are invisible. We don’t exist to them. This movement will continue until we win our ancestral rights as Indigenous people.”