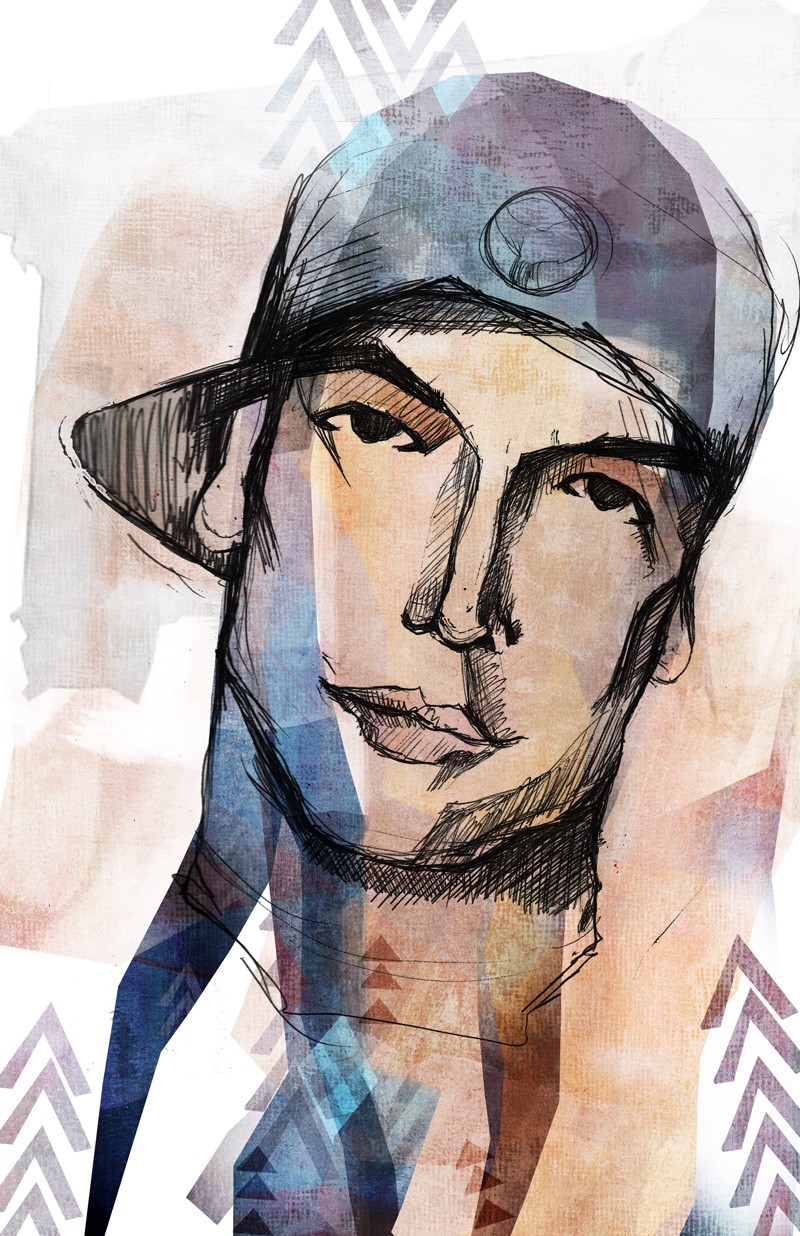

In 1985, Brad Bellegarde’s life was changed by a dance.

Amid the traditional powwow dances performed at the Canadian Western Agribition in Regina, a small group of youth gathered in a corner – not to perform a sun or round dance, but to breakdance. Seeing the dancers twist and turn on makeshift cardboard to the beat of thumping bass, blasting hip hop and MC rhymes, Bellegarde, six at the time, stood in awe.

“It was something completely different,” says Bellegarde, who now performs under the alias InfoRed. “I wanted to be a breakdancer.”

Immediately following the powwow, Bellegarde went out and bought his first rap tape, Run-DMC’s King of Rock. “I think it was a $20 tape,” says Bellegarde with a chuckle. “I played it over and over again.”

A few years later in Grade 9, Bellegarde was challenged to write a dis rap, a rhyme intended to poke fun at someone. “From that day on, I wrote rhymes every day,” he says. “They were pretty bad at first, but I stuck with it.”

Now 32, having written and produced multiple hip-hop albums and opened for rappers such as Lil’ Kim and Raekwon from the Wu-Tang Clan, Bellegarde says making rhymes is still what draws him to hip hop. “It allows me to express my creativity,” he says. “There’s no linear thinking. I can put anything together.”

Bellegarde says it’s the combination of storytelling and a musical beat that draws many young Aboriginal people to hip-hop music. “Hip hop was embraced by Native culture right off the bat.”

Chris Tyrone Ross, founder of RezX Magazine/Promotions, which targets Aboriginal youth and pop culture, agrees with Bellegarde. “There’s a huge gap between Aboriginal youth and Aboriginal culture, but not between Aboriginal youth and hip-hop music.”

Ross says rappers like InfoRed and Saskatoon’s Lindsay Knight, a.k.a. Eekwol, have great potential to reconnect youth to their culture through Aboriginal storytelling. “Eekwol is a pure hip-hop artist,” he says. “She’s cool but also educational.”

Eekwol’s songs include “Too Sick,” in which she speaks about the effects of culture loss on Aboriginal identity, and “Look East,” a song encouraging Aboriginal men to receive healing and be strong for their people, part of which is rapped in Cree.

InfoRed critiques corporate domination of natural resources and the effects that industry projects like the tarsands are having on the environment and Indigenous people in songs like “Crown Control.”

In addition to live performances and producing music, Bellegarde shares his passion with youth in schools and on reserves through workshops. His message focuses on the connection between hip hop and traditional Aboriginal culture.

In hip hop, there are four elements – MCing, DJing, breaking, and graffiti art – says Bellegarde. He compares each of these with the respective singing, drumming, dancing, and costume design of the powwow.

“It’s an easy way to break [our traditional culture] down to the youth,” he says.

Bellegarde also explains the grassroots of the hip-hop movement. “Hip hop was music made by minority groups,” he says. “It was meant to target the social issues of their day without using violence.”

Bellegarde’s experiences both as a rapper and a workshop leader have formed his belief in the redeeming power of hip hop for young people. “Hip hop shows youth how they can be productive without being destructive. Plus, it’s a big bonus to see the smile on their face when they make a rhyme.”