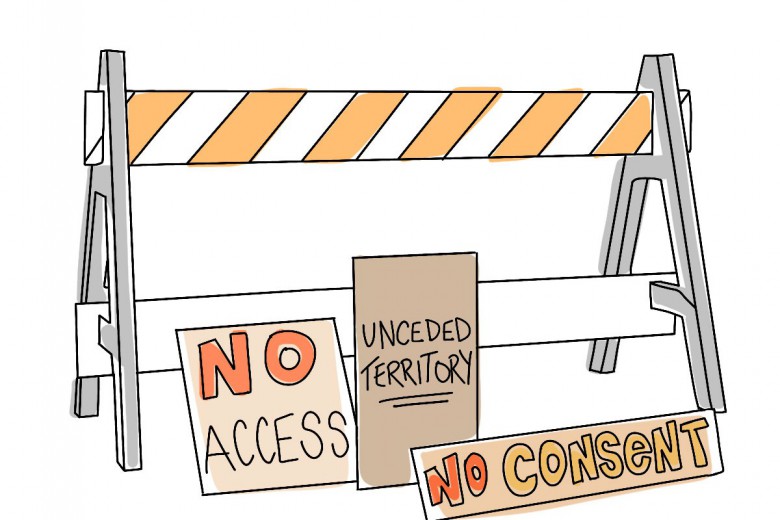

If you’ve been paying any attention to the news, you’ll have seen the images of militarized RCMP climbing over the heads and outstretched hands of Indigenous land defenders. On January 7, armed police broke down a checkpoint on unceded Wet’suwet’en territory and arrested 14 people.

Members of the Unist’ot’en House of the Gilseyhu Clan have been reoccupying parts of their traditional territory for nine years. The Unist’ot’en camp has been preventing seven proposed pipelines from cutting through Wet’suwet’en Yintah (territory) – most recently, TransCanada’s Coastal GasLink pipeline.

But what most media failed to report was that the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs were in mourning.

Three days before the raid, Chief Kloum Khun’s sister and Chief Smogolgem’s mother passed away. Some have speculated that the RCMP deliberately timed the raid to coincide with the period of mourning. “Our family, Unist’ot’en, are supposed to be standing by Smogolgem,” Chief Lht’at’en explains in a video posted on the camp’s Facebook page. “We are forced to be here taking care of our Yintah.”

Some have speculated that the RCMP deliberately timed the raid to coincide with the period of mourning.

Since the RCMP invasion, the hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en Nation have tentatively agreed to allow pipeline workers to enter their territory. They maintain that they do not consent to the Coastal GasLink pipeline being built through their traditional territory, but by granting access they are trying to forestall another confrontation, trying to keep their community safe.

As the funeral began on January 11, RCMP began dismantling the gate to Unist’ot’en.

“When someone’s grieving and there’s a death – especially with a matriarch – through our traditions, they tell us that we can’t conduct our business and we can’t do anything,” says Unist’ot’en spokesperson Freda Huson in the video. “It wasn’t that our hereditary chiefs were rolling over and saying they’re giving up, like what the world’s thinking right now.”

“It is our ritual and our culture that we support one another.” Lht’at’en adds.

I’ve been thinking about mourning – as one does, when everything is on fire and people are dying. Who and what do we mourn? How do we mourn, and what ways of mourning are respected or deemed acceptable? This issue of Briarpatch touches on these questions.

When 11 people were gunned down in a Pittsburgh synagogue in October, my partner Jon – who does Jewish anti-occupation organizing in Toronto – was visiting me in Regina. There is almost no leftist Jewish community in Regina, no one for him to mourn with. That night, the two of us stood in my living room and he recited the Mourner’s Kaddish, even though Kaddish is meant to be said in a quorum of 10. He worked for most of the next day from that same living room, remotely coordinating a vigil in Toronto that he would not be able to attend, to mourn the lives of people he had never met.

When news surfaces of civilians and militants being shot dead by the Indian army in Kashmir, I mourn. It feels like I’m mourning alone – few people in North America know about the bloody occupation of Kashmir, and those who do often defend India’s actions. The Indian state and media call these young Kashmiri men “terrorists” – a word that has been weaponized over the last two decades to brand vast swaths of brown and Muslim people as unmournable, lives that can be lost without being a loss.

We mourn people because we believe that their lives were important. To fail to mourn someone, or to stop someone from mourning, is to say that the dead person’s life didn’t matter. Mourning, like everything, is a political question and statement.

The powerful will try to convince us that some people are not worth mourning because their lives were negligible to begin with.

The Canadian state’s failure to respect the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs’ mourning shows their hand. It shows that they consider Indigenous lives and culture unimportant. But that’s hardly news.

What I’m interested in is what our mourning moves us to do. Do we allow our mourning to be weaponized to install cops in our holy places? Or do we use it – as Sterling Stutz, an organizer of the Toronto vigil for the Pittsburgh shooting victims, put it – to “[pull tighter] the ties that hold us in this struggle against white supremacy”? Can we not use it to galvanize us to rise up against occupation, against land theft, against the corporations that would profit from our destitution and death?

The powerful will try to convince us that some people are not worth mourning because their lives were negligible to begin with. In her essay “Precariousness and Grievability – When Is Life Grievable?” Judith Butler explains, “An ungrievable life is one that cannot be mourned because it has never lived, that is, it has never counted as a life at all. We can see the division of the globe into grievable and ungrievable lives from the perspective of those who wage war in order to defend the lives of certain communities, and to defend them against the lives of others – even if it means taking those latter lives.”

The work of journalists is, in a macabre way, to encourage mourning. To shed light on lives that are at risk of becoming ungrievable, and deaths that would otherwise go unseen. We must pay attention to who we are not supposed to mourn, to what mourning is under-reported or discouraged. We should teach people to extend recognition to those lives we have been taught not to grieve – and then use that grief to build stronger communities, to protect each other, and to fight back.