What would a black community look like in Vancouver? Would it look like dinner at a friend’s place, getting your hair done at Nu Nu’s Hair salon, or a black history luncheon in East Vancouver? Let’s be honest: Vancouver isn’t known for being a chocolate city, and there’s no outlying black community like Shelburne, N.S., or Ajax, ON, in sight. We have the annual Caribbean Days Festival, where hundreds of us come out to a North Vancouver park in July, but when the weekend is over, we disperse back into our integrated pockets around the Lower Mainland.

Born and raised in B.C., I know what it feels like to be the only black person in my school, on the bus, or in just about any public space. Even if you find two or three of us at the same place and time, we might lack solidarity and connection because we’re each too busy trying to fit in. Eventually we may grow into being black and proud, but we’re never comfortable being “the other.”

Lacking familial ties, I have constantly been in search of a black community. Then in 2005, I found some other people searching for that same sense of belonging and became involved with the Hogan’s Alley Memorial Project (HAMP), which was founded in 2002. HAMP was a group of predominantly self-identified black folks dedicated to keeping the black history of Vancouver alive and the present black community visible. As HAMP members, we got together to discuss both our own experiences being black and Vancouver’s black community more broadly. We held monthly meetings to explore ways to bring Vancouver’s black history to light and to better connect with past residents of Vancouver’s historic black community, Hogan’s Alley.

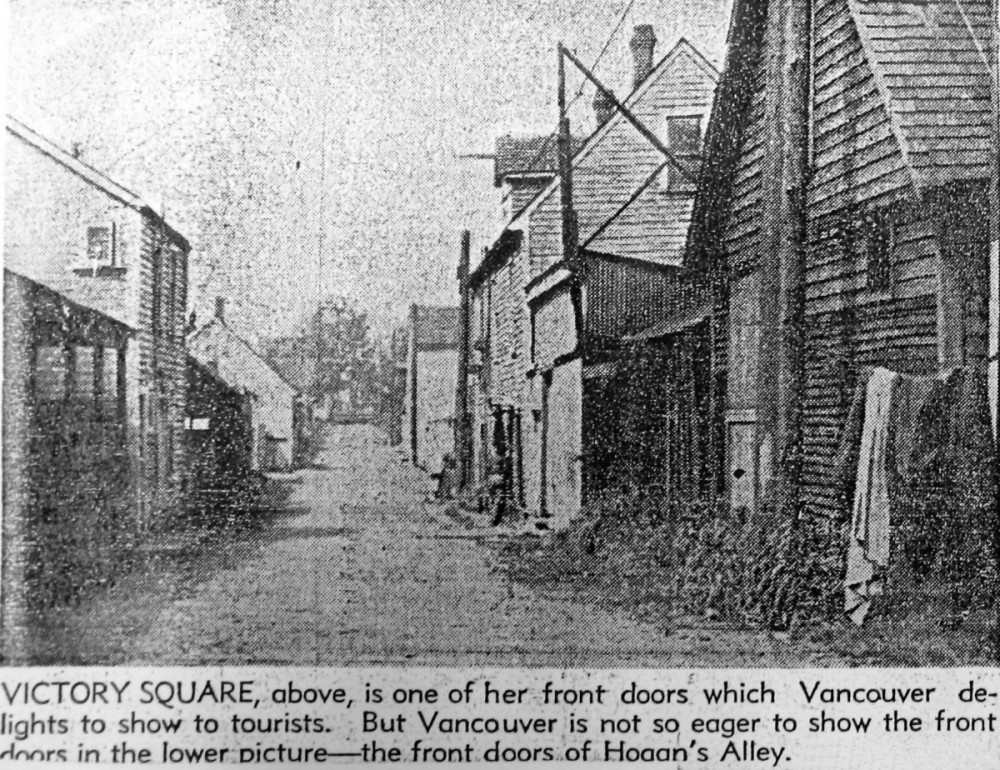

So what was Hogan’s Alley? It was literally just that, an alley, stretching from Union to Prior Streets, in the neighbourhood of Strathcona in East Vancouver. Park Lane (the formal name of the alley) and the surrounding area had a high concentration of black residents for the first six decades of the 20th century. Hogan’s Alley was the only place one could find a black church, a central foundation for black folks living there at the time.

There were also many black-owned restaurants, including several owned and staffed by black women. When performing in Vancouver, famous jazz musicians like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Nat King Cole made a point of visiting Vie’s Chicken and Steak House, a popular black-owned restaurant located at 209 Union St. in Hogan’s Alley. Ike Turner and the Mills Brothers actually performed in Hogan’s Alley at Harlem Nocturne, the city’s only black-owned nightclub, founded by jazz trombonist Ernie King.

Hogan’s Alley was a vibrant and supportive black community that unfortunately faced a lot of racial discrimination. Many residents were low-income, their homes were seen as blighted dwellings, and the nightlife was frowned upon. By 1970, most of Hogan’s Alley had been bulldozed in order to make way for the Georgia Viaduct.

The viaduct is a massive overpass that connects Strathcona to downtown and is, essentially, part of an unfinished freeway system that was otherwise successfully opposed through grassroots resistance, especially by residents of Chinatown. Canada has a long history of such racially motivated urban renewal projects, including the repeated demolitions of Calgary’s Chinatowns and the displacement of residents of Africville in Halifax in the 1960s.

As HAMP members, we were determined to make the elusive history of Hogan’s Alley more tangible. We went to the annual Black History Celebration luncheons where black families and community members came together, attended panel discussions, and spoke with relatives of Hogan’s Alley residents. We collaborated with street artists and planted a giant flower bed right on the bank of the Georgia Viaduct that read “Welcome to Hogan’s Alley.” We approached the B.C. Archives in hopes of making black historical information more accessible to the public. With Afua Cooper, a historian, author, and dub poet, and David Hilliard, an ex-Black Panther, we held an event focusing on the gentrification of black communities across North America. We even snuck inside the last residence of the Hogan’s Alley era, at 227 Union St., before it was demolished in 2007. It was three doors east of Vie’s Chicken and Steak House, and we were lucky to take some pictures and grab some memorabilia before it was torn down.

The areas surrounding what used to be Hogan’s Alley, like Chinatown and the Downtown Eastside (DTES), are currently undergoing serious gentrification themselves. But alongside these new waves of gentrification, Hogan’s Alley is being commemorated. A café opened up on the corner of Union and Gore named Hogan’s Alley Café. A Jimi Hendrix Shrine was established near the corner of Main and Union: Jimi Hendrix spent much of his childhood in Vancouver in the care of his grandmother, Nora Hendrix, who lived in Hogan’s Alley and co-founded the African Methodist Episcopal Fountain Chapel.

In February of last year, the Vancouver Heritage Foundation installed a commemorative plaque for Hogan’s Alley at Main and Union. “The plaque realizes one of HAMP’s original goals,” says Wayde Compton, an author and a co-founder of our group. The plaque publicly memorializes Vancouver’s black community. “[Before,] there was nothing that would indicate to a person walking through the area that there had ever been a black community there at one time.”

We’re all familiar with Little Italys, Little Indias, Koreatowns, and Chinatowns, but where is the Little Africa of Vancouver? Thinking of a black community, according to former HAMP member Adam Rudder, is almost whimsical. “Areas of town and monuments are all less interesting to me than the stories that weave together certain kinds of experiences and thinking about the ways in which these experiences challenge the way we think about things today,” he says. “The whole process is romantic and in certain situations it’s good. Oppressed people need a little romance; it can create hope and starting points.”

If there was a Little Africa, what would it look like? In 2007, I and fellow HAMP member Karina Vernon had a vision of a black city block inspired by all the black businesses on Commercial Drive. The specific inspiration had come when Karina showed me the book Stan Douglas: Every Building on 100 West Hastings. Opening it up, we turned to the colour insert and stared in amazement at the panoramic image of the 100 block on Hastings Street in the DTES. It was a block I walked by many times, a block that either went unnoticed or was associated with poverty and crime, comparable to Hogan’s Alley and so many other black communities across North America. This block lies across from the new Woodward’s building and today would be unrecognizable. The arresting panorama presented parallels between community displacement of the past and present-day gentrification of the DTES.

How does one reclaim space, even if just in the imagination? How could we visualize a black community in Vancouver? Commercial Drive is a place we knew had a high concentration of black-owned businesses. Perhaps we could create a black-owned city block today. We got to it with a three-megapixel, point-and-shoot digital camera (which was very sophisticated at the time) and started snapping away. We walked into each black-owned business and asked if we could take an exterior photo for the project. Everyone was friendly and helpful. We tried to capture as many black passersby as possible in the process, and we soon we realized that it wasn’t so hard to do – there were plenty of us walking around.

On Commercial, you can get plantains and patties; hear people speaking Patois, Bemba, and Somali; get your hair done; buy palm oil and a can of ackee; and dine on authentic Ethiopian cuisine. So perhaps this is what Little Africa might look like.

“The history here is particular, and there is much to celebrate and be proud of,” says Compton. “I’d like us to resist the impulse to view ourselves only in the light of other histories that are more famous or influential.” Even though the black population in Vancouver sits at a mere one per cent of residents, according to census data, we wanted to show that we are here, that we exist. We exist even if some people of African descent check the “other” box on the census form. We exist even if many folks don’t identify as black because they identify as Haitian, Nigerian, Jamaican, Ghanaian, Trinidadian, or Somalian. We wanted to show that an African diaspora has existed and still exists in Vancouver. Here, then, is your and our black city block.