“But how will you pay for it?”

This question is often asked in bad faith by right-wing curmudgeons trying to shut down conversations about a just transition. But when it’s asked in good faith, it can help us get specific about how we plan to fight for and win a new world. How do we get the money together to make a just transition happen – not just hypothetically, but here, today, in Canada, where governments are tripping over their own feet to support fossil fuel companies?

A short, oversimplified answer may be that the money can come from building non-extractive economic systems in our communities, returning stolen wealth, and leveraging strong social movements to force governments to make use of hoarded money. The longer answer is a bit more complicated.

Taxation, nationalization, expropriation

Several big-name environmental groups in Canada, including 350.org and The Leap, have thrown their weight behind the idea of a Green New Deal, a proposed transition of epic proportions inspired by a similar proposal in the U.S. These plans call on governments to make massive investments in infrastructure and services to rapidly reduce emissions and social injustices.

The problem with this strategy isn’t a lack of hypothetically available money. It’s fairly easy armchair analysis to note that in 2018, for example, the hundred richest Canadians had a total of $339 billion in assets. Between May 2015 and May 2016, just the 10 most profitable companies in Canada made $48 billion in profits – and a number of those companies have posted larger profits since. The profits of the five largest corporations in the tarsands in 2017 was $13.5 billion. The money is there, and it’s potentially available for government use if collected either through taxation, nationalization of businesses, or expropriation.

The problem with this strategy isn’t a lack of hypothetically available money.

But will governments collect and use this money for a just transition?

A recent episode in Canadian history serves as a warning. In the lead-up to the 2015 election, amid a storm of anti-Harper sentiment, a collection of labour, environmental, and faith groups organizing under the banner of the Green Economy Network (GEN) began pushing their big proposal: One Million Climate Jobs. It calls for “about 5 per cent of the federal annual budget to be invested into creating these [one million climate jobs] in public transportation, retrofitting, and renewable energy” for five years, says Bruno Dobrusin, the current campaign coordinator for GEN, in an interview with Briarpatch. For reference, 5 per cent of the 2018 federal budget would be $16.9 billion. GEN estimated this investment would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 25 to 35 per cent.

After he was elected, Justin Trudeau announced that “Canada is back” at the Paris climate talks and made bold – if largely symbolic – commitments to reduce emissions. But despite pressure by GEN, including one-on-one lobbying of Trudeau by Hassan Yussuff, president of the Canadian Labour Congress, a GEN member organization, Trudeau’s Liberals did not implement the One Million Climate Jobs proposal or anything like it.

“We were talking not so much to each other as past each other,” recalls Tony Clarke, a co-founder of GEN, in an interview with Briarpatch, of meeting with Liberal politicians after the election. “What we were trying to say was that we need a new economy altogether,” not just a jobs creation plan. But Trudeau had for years been readying climate policy that would maintain the status quo for Canada’s highly polluting economy.

Once in power, instead of taking bold action to address climate change (or to right Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples), Trudeau essentially implemented the climate plan of the Business Council of Canada, a group comprised of the CEOs of Canada’s biggest corporations. He took a business community proposal, packaged it with progressive jargon, and dubbed it the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. It’s allowed the fossil fuel industry to continue expanding on stolen Indigenous lands and posting huge profits. It has also dragged the country into a legal and publicity battle over the carbon tax. As previously described in these pages, the carbon tax is a blunt and inadequate tool to address the climate crisis (“The leftist’s case against the carbon tax,” January/February 2019).

“When you look at most of the announcements the government is making around climate policies and clean job creation, [the dollar figures] don’t get even near the numbers that we need.”

“When you look at most of the announcements the government is making around climate policies and clean job creation, [the dollar figures] don’t get even near the numbers that we need,” says Dobrusin.

Perhaps its biggest climate investment, by dollar value, was for $21.9 billion over 11 years to “support green infrastructure,” as described in the 2017 budget. That works out to about $2 billion per year, or roughly 0.7 per cent of the federal budget. But since budgets need to be approved annually, if a future government wants to cancel this funding, there is nothing stopping them. Additionally, about a quarter of the funding is going through the new Canada Infrastructure Bank, which seems poised to facilitate the privatization of public infrastructure and services through public-private partnerships.

The federal government also set up a Just Transition Task Force for Canadian Coal Power Workers and Communities and so far has committed $35 million toward financially assisting workers who find themselves out of a job as coal power is phased out. That $35 million amounts to 0.01 per cent of the federal budget of $338.5 billion in 2018; it is not an investment in infrastructure for a new economy.

The problem with relying on governments is that they won’t – or at least haven’t yet – been willing to tap into the vast reservoirs of money available to transform the economy and society, despite being asked to do so.

Along with other groups, GEN is reworking its platform and strategy. The group, which includes several national unions, has been trying to “take it slower on the big campaigning to the outside and go back internally and look at what are the best ways to engage members on these issues from each of the unions, through workshops, through trainings, all that stuff,” says Dobrusin. “It’s not all as shiny and attractive as meeting a minister,” but it’s the kind of deeper base-building that will be needed to build larger movements more able to push governments to make much-needed investments.

Taking matters into our own hands

“We have to be clear, crystal clear, that self-determination is unattainable without an economic base,” writes Kali Akuno in the book Jackson Rising: The Struggle for Economic Democracy and Black Self-Determination in Jackson, Mississippi. Akuno is the co-founder and co-director of Cooperation Jackson, a community that’s creating a solidarity economy for the Black residents of Jackson, Mississippi and the broader Kush region of Black majority counties along the Mississippi River in the states of Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Tennessee.

“Self-determination is not possible within the capitalist social framework, because the endless pursuit of profits that drives this system only empowers private ownership and the individual appropriation of wealth by design. The end result of this system is massive inequality and inequity,” he adds. “We strive to build a democratic economy because it is the surest route to equity, equality, and ecological balance.” Akuno proposes a participatory route toward eco-socialism, and he is working on the ground to build it in Mississippi.

In 2013, several grassroots organizers from front-line communities also fighting against resource extraction, pollution, and racism founded the Climate Justice Alliance (CJA). Cooperation Jackson was one of the seven original members of CJA’s Our Power campaign, with each member group facing their own unique challenges. For example, the Black Mesa Water Coalition – which in 2006 was part of a successful campaign to shut down a coal mine on Navajo and Hopi territory in Arizona – is also working on attaining food sovereignty and practising traditional ways to live in balance with the ecosystem.

“We have to be clear, crystal clear, that self-determination is unattainable without an economic base.”

“CJA came to being in response to problems like feeling under-resourced and isolated,” says Yuki Kidokoro, CJA’s national organizer for Reinvest in Our Power, in an interview with Briarpatch. Organizers agreed that while “grassroots groups have been winning at the local level, [they’re] just not as visible, not getting the resources or attention or credit for that work,” observes Kidokoro. “And it’s really grassroots organizing, particularly within front-line communities, that is a key part of the solution that’s missing or underresourced.”

CJA’s Reinvest in Our Power campaign has two parts: divestment from environmentally harmful industries, and building the infrastructure for a regenerative economy. This flows from CJA’s mission of “stopping the bad while […] building the new,” as it appears on their website.

“It’s not enough to just divest from fossil fuels, if that money from universities or cities [is] divested then reinvested in other extractive forms, like [in] banks,” says Kidokoro. How can that money be reinvested in front-line communities and stay there, instead of being taken away by predatory corporations and governments? “There aren’t enough readily available institutions or places that can handle and can govern wealth in a community and keep it in a community,” Kidokoro adds.

To meet this challenge, CJA has partnered with The Working World, a non-profit finance agency that was established in the early 2000s initially to lend money to Argentinian workers who were reoccupying shuttered factories and reopening them as workers’ co-ops. Today, the U.S.-based non-profit is building the infrastructure of what is called non-extractive lending. This means “providing financing where there’s nothing collateralized other than what’s bought with that loan,” says Kidokoro. “So nobody risks losing their house or car or personal assets. The other element is that you only pay back when you can.” This flies in the face of capitalist banks who only make loans they feel safe recouping, plus interest so they can make a profit. “And the third element is that [non-extractive financing] comes with a lot of technical assistance.”

“It’s not enough to just divest from fossil fuels, if that money from universities or cities [is] divested then reinvested in other extractive forms, like [in] banks.”

The Working World’s technical assistance is a bit like what the capitalists in the TV show Dragons’ Den promise to entrepreneurs: help with business planning, marketing, connections, and more. As Kidokoro explains about the process when workers took control of a window factory in Chicago, “The managers were gone, so [the workers] had to learn. They know the business really well, they just didn’t know the management side.”

In order to spread and build knowledge, The Working World has facilitated the creation of 22 loan funds in different communities in the U.S. These local loan funds get started with money from one shared pool of capital, and then they are lent to local projects and provide technical assistance, including training. Once those projects repay their loans, sometimes plus a bit extra to continue building the pool of funds, that funding stays with the local loan fund to seed new worker-controlled enterprises. This builds the economic base and self-sufficiency of local communities.

CJA is now in the process of establishing a Just Transition Loan Fund & Incubator, which it hopes can similarly expand to a network of local loan funds. CJA’s fund will be connected to The Working World’s revolving loan fund infrastructure, which is being renamed the Seed Commons.

The Just Transition Loan Fund aims to provide support for just transition projects. These “could be worker-owned co-operatives but they could also be other types of community- or worker-governed enterprises that are connected to our members,” says Kidokoro. “For us it’s really important to have that connection […] so that it doesn’t become an insular project that’s just benefiting primarily the people who are directly in it, but that they’re connected to a broader systemic change effort.” This support could be financial – like directly funding just transition projects – or it could mean providing labour, equipment, or expertise. For example, a landscaping worker co-op could both donate money to a nascent food sovereignty project and help them plan, plant, and maintain a garden.

“For us it’s really important to have that connection […] so that it doesn’t become an insular project that’s just benefiting primarily the people who are directly in it.”

In addition to supporting projects and new local loan funds, CJA also aims to provide “political and popular education about what non-extractive finance is” through the initiative, says Kidokoro. To this end, CJA held a training last year, launched an educational website and held a webinar that is now freely available on YouTube.

Lastly, CJA is exploring how the loan fund can provide land-based support for projects – meaning securing greater control over land, either through ownership or changes to legislation. This prevents its member organizations, and individuals in those organizations, being displaced by gentrification or resource extraction industries.

By Kidokoro’s admission, CJA’s Loan Fund is “new for us as a movement, it’s not [yet] super developed,” and – as of the time of the interview – no loans had been made from it. “We’re hoping to get the first one out the door in the next couple months,” she explains.

Networks of co-operatives

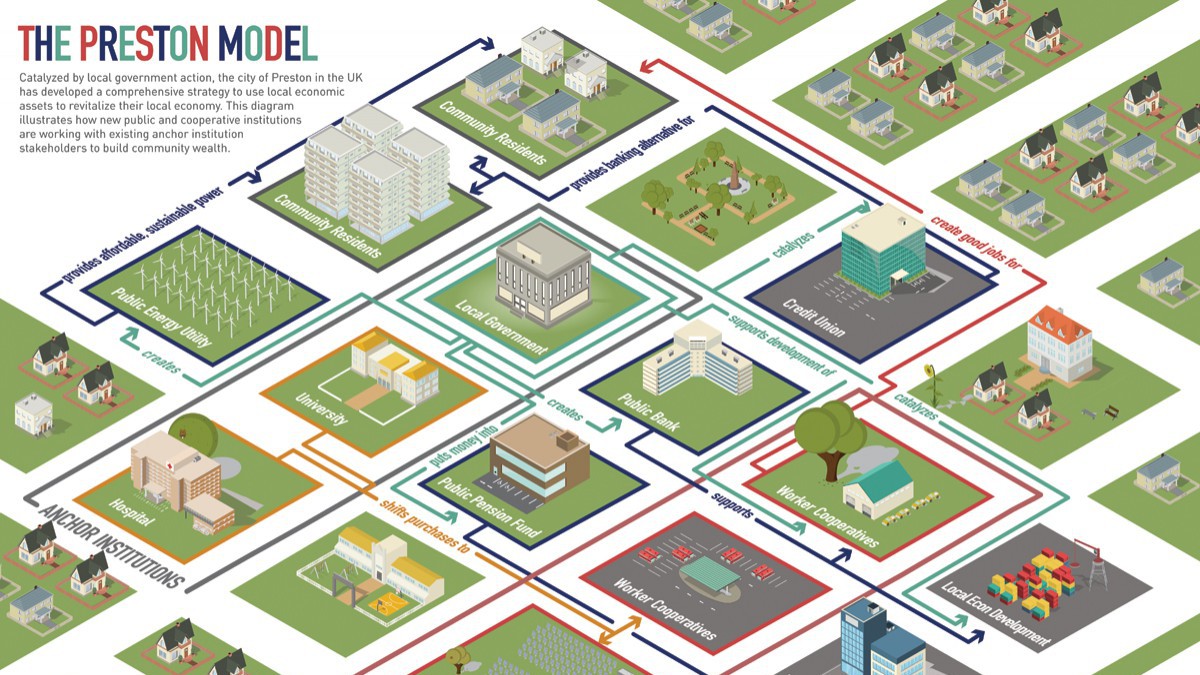

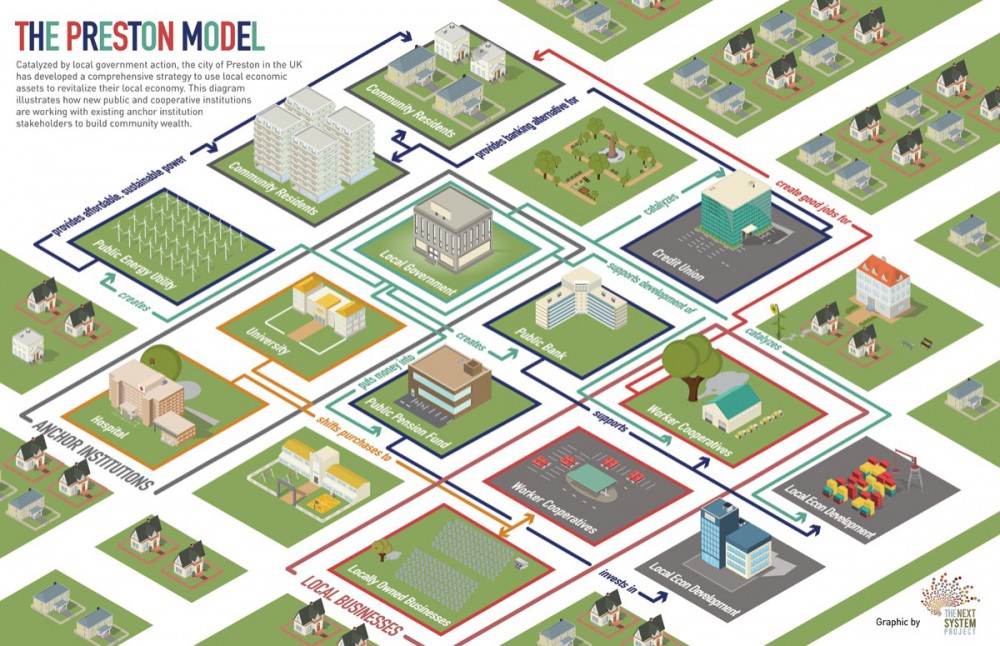

Efforts to build non-extractive economies are, in some places, fairly advanced and have extended beyond worker co-ops and land trusts. While not as explicitly ecologically focused, former industrial towns like Preston, England, and Cleveland, Ohio, have involved other institutions in their non-extractive economies. Often referred to as the Preston Model or Cleveland Model, these communities establish a network of co-operatives that supply local anchor institutions, like universities, hospitals, and other government operations. The intention is to keep wealth in the community as opposed to it being siphoned off by big corporations.

What could this look like in communities in Canada? It could be a local worker co-op installing solar panels for a Canada Post office. A supportive credit union in the community feels comfortable giving them a loan to expand, so they can begin to install heat pumps and geothermal heating, too. Another anchor institution, a hospital, is on board with local purchasing after recently buying half of their food locally and seeing the positive reaction from patients and the community. Buoyed by that success, they decide to install solar panels using the workers’ co-op. On top of paying its workers decent wages, the worker co-op begins turning a profit, which it does not need to pay out to shareholders. The group democratically decides to use its profits first to contribute to the legal fees of a local First Nation fighting industrial logging on its lands and second to help establish a local loan fund, which will be easily accessible for other just transition projects.

The intention is to keep wealth in the community as opposed to it being siphoned off by big corporations.

While this model works best with relevant governments enthusiastically on board, much can be done without support from the state by building up worker co-ops and getting anchor institutions to participate by purchasing goods and services.

Building economic independence and power through worker co-ops is not particularly new, and it is not without its share of difficulties. In Winnipeg, a Mondragon worker co-op bookstore and café operated from 1996 to 2014, with an explicitly anti-capitalist mandate. A core group, many of whom identified as anarchists, held the operations together for many years, but declining revenues and membership numbers contributed to its ultimate demise. This brought up an important question at the time, which remains relevant: How can we sustain non-extractive enterprises without taking time and energy away from building social movements, when there are a limited number of activists working in both directions?

Other major co-operatives in Canada include Mountain Equipment Co-op (MEC) and Federated Co-operatives Limited (going by the retail name “Co-op”). These co-ops have been financially successful, but they’re arguably not building non-extractive economies. MEC has been moving from selling locally made products to selling products made overseas, and the bulk of Co-op’s revenues are from oil extraction, refining, and sales. Both of these co-ops are consumer co-ops, meaning they operate to benefit the consumers, as opposed to worker co-ops, which are controlled by the workers. Financial benefits of MEC and Co-op are passed on to customers in the form of lower prices and, in some cases, partial refunds. Co-ops of their size and power will need to be reoriented if they are to play a supportive role in just transition work.

Philanthropy in the transition

Wealth accumulation is the result of theft – “stolen labour, stolen land, stolen natural resources,” as Kidokoro puts it – and redistributing wealth will be a key part of a just transition. A growing movement of funders is breaking with philanthropic practices that have historically entrenched the control of the wealthy elite. Instead, they see philanthropy as an act of returning what has been stolen and of empowering people and communities to develop their own solutions. That can look like forgivable loans, meaning loaning money with no hard expectation of repayment, let alone of recouping interest.

For example, The Working World draws from a shared pool of money to set up local loan funds. Some of that money was raised from donors, including foundations, and is called “gift capital,” meaning “donations to be able to loan.” This initial donation finances projects that are deemed too risky for loans by banks and even credit unions.

Instead, they see philanthropy as an act of returning what has been stolen and of empowering people and communities to develop their own solutions

Another example is the Chorus Foundation, which, according to its website, “works for a just transition to a regenerative economy in the United States.” Chorus came into being after its founder, Farhad Ebrahimi, committed US$25 million of the inheritance that he’d received as a teenager in the early 2000s to the foundation. Understanding the urgency of the climate crisis, the foundation is spending all its money by 2024, in contrast to most foundations which aim to operate in perpetuity, giving out only a small portion of their assets annually and replenishing their money through capitalist investments. And unlike more mainstream foundations that choose to fund highly professionalized environmental groups, some of which toe status-quo political lines, Chorus funds front-line communities which are stopping environmentally harmful projects and building solutions. “At Chorus, we believe that we should be supporting movement organizations to do what they think needs to be done,” writes Ebrahimi in a 2015 reflection article.

Bad funder behaviour, says Kidokoro, includes “controlling, trying to set an agenda, trying to convince you to do something which may not be consistent with your values, and offering a grant to do something completely different [from what you proposed].” But CJA has had solid funder allies, she says, including the Chorus Foundation. “I think part of [the reason for that] is there’s a values and analysis alignment, and relationships. The relationship has never felt like a power imbalance. Like, we’re in this thing together and this is the role they play and this is the role we play and it’s been really helpful to be in relation with each other in that way and sharing learning.”

In Canada, one group organizing around returning stolen wealth is Resource Movement, a group of young people with wealth and class privilege “working towards the equitable distribution of wealth, land and power,” according to its mission statement. (Disclosure: the author was a co-founder of Resource Movement and is currently a member.) Resource Movement provides education for members and encourages giving money to front-line communities – for example, they’ve fundraised with RAVEN for the Beaver Lake Cree Nation’s legal case against the Albertan and Canadian governments and the tarsands. To date, though, nothing on the scale of the Chorus Foundation has been initiated in Canada.

Understanding the urgency of the climate crisis, the foundation is spending all its money by 2024, in contrast to most foundations which aim to operate in perpetuity.

Resource Movement and others are working to shake up Canadian establishment philanthropy, which often tends toward funding apolitical institutions like universities, hospitals, private schools, art galleries, opera houses, and museums. In many cases, this philanthropy only solidifies the status quo. In other cases, like the philanthropy of late Barrick Gold baron Peter Munk, funders may give high-profile donations to hospitals while also quietly funding efforts to push for environmental deregulation, defunding public services (like health care), and providing platforms to white nationalists (like hosting Steve Bannon at the Munk Debates).

Philanthropy that addresses root causes, with the intention of returning stolen wealth, seems to be a small fraction of philanthropy in Canada. We need to scale it up to support front-line just transition work – but it remains to be seen whether funders will actually begin to put their money where the crisis is.

“All of the above”

So, what should we do to build up the financing, and the financial skills and tools, to make a just transition happen? Should we ride the Green New Deal wave and appeal to the state for massive investment? Or build community power from the ground up, relying on philanthropy or non-extractive economies that we construct ourselves?

Kidokoro at CJA doesn’t see the two as mutually exclusive. “I think for us it’s a ‘both/and.’ Nobody has all the solutions, otherwise we’d be in a different place. It seems like we need to be doing all of the above.” But just the fact that the Green New Deal proponents are talking about the state investing billions of dollars in a transition is a significant shift in popular discourse, even if it is being co-opted by business interests as the plan moves from idea to policy. “It’s pretty incredible that this conversation is happening,” says Kidokoro.

It’s up to us to build on this momentum. Identifying potent strategies and developing real, tangible plans to fund the transition will take a lot of discussion. That can happen anywhere – in kitchens, classrooms, on the job, at city council meetings, online, at community centres, in the streets. Efforts on the ground are already underway. There’s lots of work to do, and money to get moving.

_780_520_90_s_c1_c_c.jpg)