In early 2020, plans were underway for the Toronto Abolition Convergence – an international gathering of activists, educators, and community members working toward the end of violent state structures like prisons, police, and borders. Importantly, the convergence would feature letters from incarcerated people answering the question “Can you imagine a world without prisons?”

The first batch of requests for letters went out to prisons in the U.S. As organizers prepared to start Canadian outreach, COVID hit, and the convergence was postponed – but the correspondence committee continued, constituted now as the Inreach collective. When prisoners began writing back, Inreach brought their responses to Briarpatch Magazine, and the idea for the Prison Abolition Issue was born. Other abolitionists, like members of Free Lands Free Peoples, an Indigenous-led group organizing for and with prisoners on the Prairies, joined the project. With renewed capacity, we now added writing and art by prisoners in Canada.

Roughly 10 members of the editorial collective – comprised of Inreach and Free Lands Free Peoples members, and Briarpatch staff – have met every two weeks since April to shape this special issue. We have had conversations about the ethics of editing prison writing; creating care and safety for our readers and writers; and the mechanics of working against prisons from both inside and outside them.

Communicating with people in prisons is hard, for many reasons. Prisons are designed to isolate, demoralize, and invisibilize the people inside – prisoners’ mail is often screened, confiscated, or lost, and one can never be certain whether a letter has made it into or out of a prison. Prisoners’ phone calls can be exorbitantly expensive and some last for just 20 minutes before being cut off. There is little to no internet or computer access. Prisoners are threatened and punished with losing the “privilege” of communicating with people outside. Out of necessity, the writers, artists, and editors of this issue learned to be creative, crafty, and persistent in our communication.

Prisons are designed to isolate, demoralize, and invisibilize the people inside – prisoners’ mail is often screened, confiscated, or lost, and one can never be certain whether a letter has made it into or out of a prison.

But this wouldn’t be a Briarpatch special issue unless it demanded new ways of thinking about the mechanics and ethics of publishing a magazine. While making this issue, editors asked: who are we, especially those of us who have never been imprisoned, to edit prisoners’ writing? Prisoners are subject to intense surveillance and micromanagement, and their experiences are often silenced or dismissed. As editors, we did not want to contribute to what prisoner justice advocate Cory Charles Cardinal has called the “muzzling” of prisoner voices. We decided to edit lightly, without changing writers’ voices or ideas. That meant we edited for clarity and accuracy – defining legal jargon and verifying factual claims wherever possible – but did not insert our own analysis, research, or examples unless writers asked us to.

We also struggled to find ways to send payments and magazines into prisons – not knowing if a magazine bound with staples, or with the words “prison abolition” on the cover would get in. We changed our binding and removed the cover text on some of the copies. We got in touch with organizations that send books to prisoners, and through their programs, we are sending hundreds of copies into prisons. We hope these copies make it to our incarcerated community members, but we know that many of this issue’s contributors may never get to hold a copy of the magazine in their hands.

This issue was inspired by, and owes a great debt to, the long history of prison publications in Canada and the U.S. At their height in the 1950s and ’60s, there were more than 250 such publications in Canada and the U.S., with an estimated readership of two million. Melissa Munn, a professor at Okanagan College who maintains Penal Press, an archive of prisoners’ publications, explains that they “came out of a really hopeful era when people were still very much engaged with the treatment of prisoners. [...] People believed that we could do better, that we could use prisons more sparingly, that when we did incarcerate people, we were going to give them opportunities to improve themselves.” But the last few decades of politics in North America have been marked by law and order politics, the war on drugs, and a widening gap between rich and poor. Today, there is more secrecy and censorship around what happens inside prisons; politicians respond to social issues by blaming “superpredators” and “terrorists,” and promising longer and harsher sentences while mainstream media cheers them on.

"People believed that we could do better, that we could use prisons more sparingly, that when we did incarcerate people, we were going to give them opportunities to improve themselves.”

But change is in the air. Because of the uprising for Black liberation in the summer of 2020, more people are voicing criticisms of incarceration, and we’ve seen movements to abolish prisons gain unprecedented momentum. Abolitionists have pushed fiercely and often successfully against the expansion of the prison-industrial complex – cancelling programs that stationed police in schools in Toronto, Peel, Waterloo, and Ottawa, and suspending the one in Edmonton; opposing Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s plan for a new prison in Kemptville; and organizing weekly noise demos outside of immigration detention centres. In the U.S. in 2019 alone, New York city council voted to close Rikers Island, Los Angeles county decided against two new jails, and Atlanta shut down a city jail.

In part because of the differences between prison abolition movements in Canada and the U.S., we are excited to use this issue to put prisoners on either side of the colonial border in conversation. For many years, abolitionists in Canada have been building on local and foundational work by Indigenous and Black organizers and scholars, coalescing in greater numbers and with greater coordination – but unlike in the U.S., we’re only just arriving at a point where we can begin to call the formations a movement. Still, prison abolition has deep roots here. Anishinabe-Métis scholar Aimée Craft reminds us that the history of prison abolition on this land stretches back to at least 1871, when the Anishinabeg refused to negotiate Treaty 1 until the British Crown released imprisoned community members.

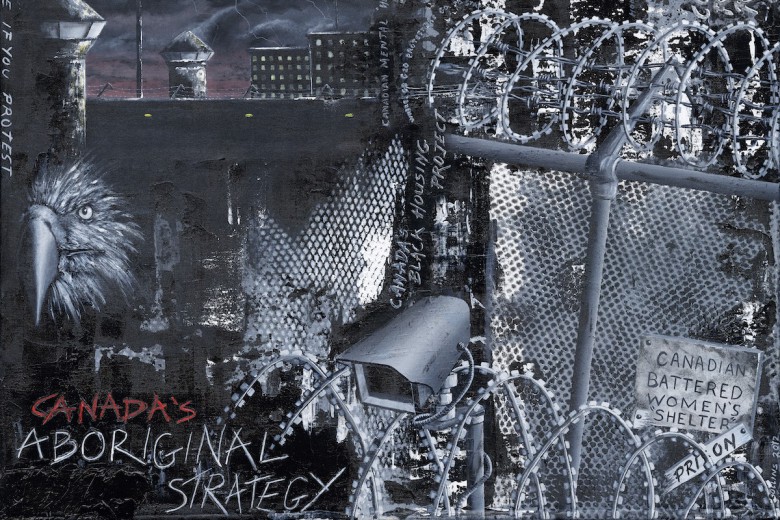

In the U.S., the abolition movement often focuses on how prisons are a direct outgrowth of slavery – and this framing makes sense, when Black people in the U.S. are five times more likely to be arrested than white people. In Canada, many abolitionists have called Canada’s prisons the “new residential schools” – institutions designed to remove Indigenous people from their lands, strip them of their languages and cultures, and isolate them from their families. Indigenous women, in particular, are being incarcerated at an alarming rate – they are the fastest growing prison population in Canada, and now make up 42 per cent of women in federal prisons. Readers will notice that many of the writers imprisoned in Canada are Indigenous, and five are from Saskatchewan, which is arguably the beating heart of Canada’s colonial enterprise. Our writers and artists imprisoned in Canada have a distinctly anti-colonial analysis of Canadian prisons – an analysis we think is essential for all prison abolitionists.

In Canada, many abolitionists have called Canada’s prisons the “new residential schools” – institutions designed to remove Indigenous people from their lands, strip them of their languages and cultures, and isolate them from their families.

While making this issue, we also talked extensively about creating care and safety for our writers and our readers, not knowing into whose hands this issue might find its way. We considered whether to include content warnings on articles; whether searching the names of our writers online was ethical; whether to refuse to work with writers who had hurt others. We decided against all three. Capitalism, colonialism, and the prison-industrial complex entangle all of us in a system of enacting and suffering harm, whetting our appetites for punishment, and destroying our abilities to care for each other and be in good relation with one another. We must extricate ourselves carefully, seeking justice and healing for those hurt as well as those hurting.

Many prisoners have survived multiple layers of trauma, including incarceration itself. As a result, some writers discuss painful topics in their essays. Many write about violence; abuse; and the immeasurable injustices perpetrated against them, their ancestors, and their community members. Readers, please take care while reading this issue.

Over the past two years, the public conversation around abolition has focused in large part on the defunding and dismantling of police. This conversation is certainly vital, but equally important is a robust consideration of the need to abolish prisons. Both work together as components of the larger penal system, which functions to remove, control, and punish so-called “deviant populations” in the service of settler colonial and capitalist interests. By featuring the often-silenced voices of incarcerated people, we hope to amplify the knowledge of those who have experienced this system of oppression first-hand. Through their creative wisdom, we come to understand the horrific reality of prisons more deeply and begin, with great care, to imagine something new in its place.

The Prison Abolition Issue Editorial Collective

Sophie Birks

Fathima Cader

Carry Cardinal

Lorraine Chuen

Saima Desai

Yaniya Lee

Phillip Dwight Morgan

Mark Mullkoff

Swathi Sekhar

Abby Stadnyk

Fact-checking and anonymity

Like in other Briarpatch issues, every article in this issue was fact-checked. We take care to verify names, dates, laws and regulations, numbers and dollar figures, and geographic and historic statements. But many authors also wrote about what they had seen or experienced first-hand inside prisons, and we were not able to fact-check all of these claims. Briarpatch’s fact-checkers often rely on mainstream media articles or official government documents to verify claims, but these sources can be unreliable when it comes to prisons; they can overlook or downplay the abuses and bad conditions inside. We chose to publish our authors’ first-hand experiences, even when we couldn’t verify them, because we think that prisoners’ observations are an invaluable source of information about what really happens inside prisons.

Some writers also chose to write under a pen name or remain anonymous. Many have upcoming parole hearings or court dates, and they were justifiably worried that their criticisms of the prison system would lead to retaliation by judges, prison administrators, or correctional officers, should they use their real names.

Send a letter to writers or editors

The writers featured in this issue are excited to hear readers’ feedback on their contributions. Prisoners are deliberately and cruelly cut off from creative and political communities outside of prisons, and we want to break that isolation by inviting readers to send feedback to writers.

To send feedback to one or more writers, please write a letter and send it either:

- via email to [email protected], with the name of the author(s) in the subject line;

- Via snail mail to Briarpatch Magazine, 2138 McIntyre Street, Regina, Saskatchewan, S4P 2R7. Please include the name of the author(s) near the beginning of your letter.

Emails will be printed out, and will be collated with physical mail into packages addressed to each individual writer. You can include your own mailing address, if you’d like a response to your letter. Please send your mail before November 1, 2021.

What you write in your letter will be visible to Briarpatch staff, and may also be read by prison administrators – please do not write anything that might put you or your correspondent at risk. You can find a list of things you are not allowed to send to a prisoner in Canada at this link.

We also welcome responses to the issue in the form of letters to the editors, which we may choose to print in the forthcoming November/December 2021 issue. Send letters to the editors by emailing editor [at] briarpatchmagazine.com, with the subject line “Prison Abolition Issue: letter to the editors.”

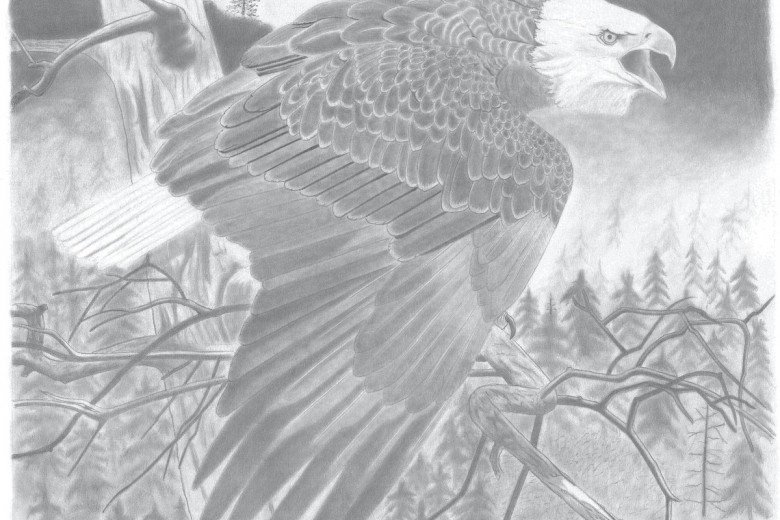

About the cover art

The cover artwork for this issue is American Goldfinch (2011) by Peter Collins. Collins was a lifer at Bath Institution near Kingston, Ontario. He died of cancer in 2015, after 32 years in prison. He was well-known for his love of birds and began to make art about them while incarcerated. The cover art is part of The Jailbird Series, a collection of mixed media artworks depicting birds alongside prison architecture.

Collins was known to feed and care for birds on the wall ledges or doorways of his prison unit. Already perceived as a troublemaker for his subversive art, he worried about getting caught by prison guards, so he taught other prisoners how to make bird food and feed the birds instead. Even after Collins’ death, prisoners still reportedly care for birds around the Bath prison.

For more about Collins and his art, read “Of Birds, Ointments, and Care: How Peter Collins’ Artworks Kept Him in Prison” by Sheena Hoszko in Mice Magazine, and watch Collins’ short film Fly in the Ointment (2015) on YouTube.

The editors

The following people helped create the Prison Abolition Issue. Some of them – those named above – were members of the editorial collective, and they attended meetings to help shape and guide the entire issue. Others worked with one specific writer to polish and publish their work. Some editors have chosen to use pseudonyms or remain anonymous in order to protect their jobs, privacy, or access to contacts in prison.

Anonymous is involved in abolitionist organizing and recently graduated from law school.

Fathima Cader’s writing has appeared in Guernica, The New Inquiry, Hazlitt, and elsewhere. She previously practised as a human rights lawyer.

Carry Cardinal is a nehiyaw iskwew living in amiskwaciy. Her family is from Bigstone Cree Nation on Treaty 8 territory. She is a penal abolitionist and a member of Free Lands Free Peoples who wants to remember and build worlds where we take care of all our relations.

Lorraine Chuen is a law student and writer living in Toronto.

Saima Desai is the editor of Briarpatch Magazine. She’s a settler splitting her time between Treaty 4 and Dish With One Spoon territories, and her family is originally from Gujarat, India.

Sophie Jin is a Chinese writer, researcher, and master's student.

Yaniya Lee is a writer and critic interested in the potential of collective organizing for institutional power. Lee was features editor at Canadian Art from 2017 to 2021 and she is now a Ph.D. student in gender studies at Queen’s University.

Phillip Dwight Morgan is a Toronto-based writer of Jamaican heritage. His writing explores themes of race, representation, and state violence.

Sam Misra is a community-based researcher and law student based in Toronto.

Mark Mullkoff is a narrative therapist, DJ/producer, and a father who resides as a settler in Tkaronto. He dreams that his child will see a world where prisons and other harmful institutions no longer uphold white supremacy, colonialism, and capitalism.

Swathi Sekhar is a queer Tamil femme, refugee lawyer, and prison abolitionist living in Tkaronto, on Turtle Island.

Brett Story is a filmmaker and writer based in Toronto. She is the director of the film The Prison in Twelve Landscapes and a longtime anti-poverty and prison abolition activist.

Abby Stadnyk is a white settler based in Edmonton, a member of Free Lands Free Peoples, and a contributing writer for Perilous Chronicle.

Reakash Walters is a writer and a criminal defence lawyer who grew up on the Prairies and is currently based in Toronto.

Sara Wylie is a non-fiction filmmaker, producer, and researcher currently residing on the unceded traditional territories of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) Nations.

_780_520_90_s_c1_c_c.jpg)