“If you unfold the thread of harmful drug policy through history […] it’s nothing but racism,” says Naja Kassir, community engagement and education coordinator for Canadian Drug Policy Coalition.

In 2023, community leaders in Surrey, B.C. raised the alarm on the high rates of toxic drug poisoning deaths among South Asian international students. They described a tragic situation where local gurdwaras were financially supporting the return of these young students’ bodies home to their families still abroad. Race-based data is not collected as part of the B.C.’s emergency overdose response.

“The deaths are devastating, and the worst part is they are preventable, but no one is doing anything to address the toxic supply,” says Robin,* a member of the Surrey Union of Drug Users’ (SUDU) South Asian Committee. “Simply providing multilingual harm reduction and overdose response information to newcomers would be a small but life-saving step.”

And this tragic trend is not new. Statistics Canada data shows that South Asian immigrants were overrepresented in immigrant toxic drug poisonings prior to the declaration of a public health emergency in B.C. And a report from a local health authority shows that between 2015 and 2018, toxic drug deaths rose 117 per cent more among South Asians in the Fraser Health region, where Surrey is situated, than among non-South Asians.

Canada’s criminalization of drugs through early versions of the colonial Indian Act is one of many tools the settler-state used to maintain control over anti-colonial resistance. They did so by targeting Indigenous Peoples – and to a lesser degree, settlers – through incarceration and fines.

The laws and policy frameworks that govern the use, possession, production, procurement, and sale of drugs are rarely only about control over a substance.

Webs of empire

Canada’s criminalization of drugs through early versions of the colonial Indian Act is one of many tools the settler-state used to maintain control over anti-colonial resistance. They did so by targeting Indigenous Peoples – and to a lesser degree, settlers – through incarceration and fines.

The British-led colonial government used the Indian Act to restrict access to substances in so-called Canada, and in doing so, acted as if its history of drawing massive profits from the production and supply of opium in India was non-existent.

Although policies changed over time and differed regionally across India, through it all, the government maintained a monopoly over opium profits. The profits were so lucrative, that when China sought to stop the import of opium from British-ruled India, the British government pursued the Opium Wars to forcibly ensure they could continue profiting through sale of opium to China.

The British government’s selective use of moral outrage to first create the category of illicit drugs, then its control of these substances to assert dominance over populations, all while reaping economic benefits as it colonized more land, demonstrates how settler and imperialist states use drug control as a tool of power. Canada’s collective drug laws also align with the international “War on Drugs,” which broadly replicates socio-economic patterns of racial capitalism the world over, in another example of the Global North extracting from the Global South.

Control over and criminalization of drugs are intertwined in the legislation that governs everyday life across Canada and provincially, including policies for child protection, workplace conduct, detention and deportation, probation conditions, tenancy in subsidized housing, and as grounds for displacement from public space.

Racial capitalism, in short, is an understanding of power that sees racism and economic exploitation as interlocking, rather than separate relations of power with distinct histories.

Today, one of the major recent examples of how the drug war upholds Western imperialism is through the production of violence and instability in Palestine.

U.S.-headquartered pharmaceutical company Indivior and Israel’s Teva Pharmaceuticals manufacture and distribute some of their supply in Israel where they benefit from cheaper, stolen land, and access to a captive Palestinian market which has limited consumer choices. They also benefit economically from U.S.-based state and local subsidies and U.S.-backed conflict in the region that drives a need for pain management. These same companies lobby states around the world to promote their opioid products, even under pretexts of efficacy, obscuring the causes of the toxic drug crisis.

Companies that control the legal and “acceptable” supply of drugs are worth billions (or tens of billions). Meanwhile, community-run drug access alternatives, such as the Drug User Liberation Front’s (DULF) compassion club, experience raids and criminalization, despite its overwhelmingly beneficial operation from August 2022 until its shutdown in October 2023.

Control over and criminalization of drugs are intertwined in the legislation that governs everyday life across Canada and provincially, including policies for child protection, workplace conduct, detention and deportation, probation conditions, tenancy in subsidized housing, and as grounds for displacement from public space.

Premier David Eby’s push against harm reduction

Under current NDP premier David Eby, B.C. has taken a dark turn back to institutionalization as the solution to the toxic drug crisis. Beginning in October 2023 with the raids on and subsequent arrests of the founders of DULF’s compassion club, there have been multiple crackdowns on drug user rights and harm reduction movements in the province.

At the time of DULF’s shuttering, Eby stated “It’s unfortunate because they were providing essential life-saving work. But they were also breaking the law, which we will not tolerate.”

Eby is rapidly pushing his vision of expanding forced treatment through prisons and psychiatric wards. Eby has been accused by a Richmond city councillor of personally interfering against the opening of an OPS in the city's hospital. Meanwhile, the B.C. government scrapped plans for at least two other hospital OPS sites, according to government documents obtained by Filter Magazine. The B.C. NDP has also attempted to increase police powers of displacement through Bill 34, their failed Restricting Public Consumption of Illegal Substances Act. Under the guise of banning public drug use, Bill 34 sought to criminalize “recent” suspected substance use, as determined by police discretion, through fines, displacement, and arrests without warrants.

SUDU puts up 1,800 flags in Surrey on International Overdose Awareness Day in August 2024 to represent the 1,800 people killed in Surrey by toxic drugs since the B.C. public health emergency was declared in 2016. Photo courtesy of authors.

After a year-long fight, including a successful legal battle led by the Harm Reduction Nurses Association for an injunction preventing Bill 34 from coming into effect until a full Charter challenge could be launched, the B.C. government finally repealed the legislation.

In a speech responding to Bill 34, Kawacatoose First Nation Elder Mona Woodward, with the Surrey Union of Drug Users (SUDU), reminded us how expanded police powers would target Indigenous people, stating that “Canada depends on killing Indigenous people for this state’s survival” and that “to take our land and our resources, they are continuing to wage a war on our people.” The Union of BC Indian Chiefs was one of the earliest organizations to raise the alarm on Bill 34.

In a 2023 letter to B.C.'s solicitor general, SUDU (under its former name Surrey Newton Union of Drug Users) also highlighted how the decision to increase police power replicates patterns of colonization and does not address the causes of the toxic drug supply crisis – which has contributed to First Nations peoples’ life expectancy in B.C. decreasing by 7.1 years since 2019.

This state-promoted exploitation of people as a means of cheap labour and profits has led to increased numbers of migrants, considered disposable by employers, ending up unhoused, in shelters, or reliant on unregulated substances to manage these exploitative circumstances.

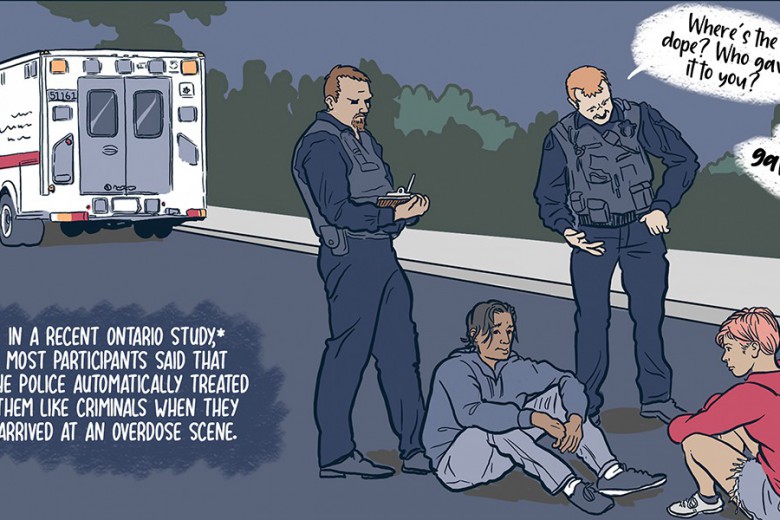

While then-solicitor general Mike Farnworth told CBC that police officers wouldn’t weaponize their expanded powers, the reality is that police forces across B.C. have always weaponized their discretion against certain populations – including people who rely on public space and those who use drugs – through harassment, the seizure of belongings without charges, and other targeted practices.

Provincial governments, health authorities, and their non-profit industrial complex counterparts in other parts of the country are also attacking drug user rights and rolling back evidence-based public health interventions such as sterile needle distribution in Saskatchewan and supervised consumption sites in Ontario.

Racial capitalism and the crisis

Intersections between the war on drugs and racial capitalism are also clear when looking at the experiences of the South Asian diaspora, as evidenced by the rising toxic drug poisoning deaths among international students.

For decades, the Canadian state has abetted the exploitation of international students and temporary foreign workers, disproportionately from India, to grow the domestic economy and prop up its underfunded post-secondary system.

Canada’s Temporary Foreign Workers Program was described as a “breeding ground for contemporary forms of slavery” by a United Nations’ special rapporteur, and numerous reports have highlighted how international students are predatorily recruited, particularly by deregulated private colleges, and subject to abuse and exploitation upon arrival.

This state-promoted exploitation of people as a means of cheap labour and profits has led to increased numbers of migrants, considered disposable by employers, ending up unhoused, in shelters, or reliant on unregulated substances to manage these exploitative circumstances.

The toxicity of the drug supply here, relative to the jurisdictions from which most people are recruited, places newcomers at elevated risk of drug poisonings.

Dehumanization

State narratives are then carefully crafted to justify violence toward and the social abandonment of racialized communities.

For instance, as part of a revived trend of xenophobia, Canada’s Immigration Minister Marc Miller recently announced plans to crack down on migrants whose temporary visa period has ended or will be ending soon, dismissing the numerous migrant-led campaigns for increased pathways to residency.

Canada weaponizes precarious immigration status as an excuse for disposal after extracting value from migrant workers. Drug war policies are one mechanism the state uses to surveil, track, and document people with precarious status, deporting them as soon as they can.

Since the 1980s, police and the media have overemphasized South Asian involvement in gangs and organized crime. In 2022, the B.C. anti-gang police agency infamously named 11 South Asian men in a “most-wanted list” that was criticized by community members for how it would exacerbate random checks and racist profiling.

Bill 34’s expansion of police powers to target “suspected” recent substance use would also have promoted these racist practices. In SUDU’s letter to B.C.'s solicitor general, they described how the lack of services in Surrey’s Newton neighbourhood, where South Asian people represented almost 60 per cent of the population in 2016, compels South Asian people to use substances outside. In Newton, the closest supervised consumption site is more than an hour away on foot.

Public drug consumption is a noted survival strategy in a context where using alone can mean dying, but public health institutions are promoting the narrative that the disproportionate deaths are a function of “cultural stigma” within the South Asian diaspora, while concealing their own neglect.

When Fraser Health released their analysis showing that South Asian people were dying disproportionately in the region, the medical health officer stated “There’s a lot of work that needs to occur to just start having those conversations, and make people comfortable to just even talk about this around drug use.” No new safe consumption sites have since been opened in Surrey.

Weaponizing “cultural stigma” allows the state to avoid scrutiny and places blame exclusively on South Asian people for their own death during a crisis, conveniently distancing the state from any responsibility.

“The deaths and struggles of South Asian people who use drugs have gone largely neglected in this eight-year-long public health emergency.”

This is despite evaluation after evaluation, including those commissioned by the B.C. government itself, finding that racist and settler-colonial power and exclusion permeate health-care systems in every province.

Sterilization of a movement

Public health organizations interpret the term “harm reduction” to describe singular interventions, such as a needle exchange or a supervised consumption site, but they are either unable or unwilling to integrate justice-oriented visions of harm reduction such as refusing criminalization of drug use.

“In our movement, we are losing that logic of where harm reduction was even born,” says Kassir, describing direct actions and mutual aid taken by ACT UP during the AIDS crisis (ACT UP-New York has also continued to be active in Palestinian solidarity), as well as collectives that have led the struggles for trans and reproductive justice.

“The government is so good at capturing movements; it’s refined. That machine is so refined,” adds Kassir. “But it has fundamental flaws, it requires mass suffering, and historically, people have found each other and organized around shared struggle.”

The South Asian committee

The institutional co-option of harm reduction has contributed to the erasure of racialized voices in the harm reduction movement, as well as anti-racist resistance.

In the face of social abandonment, SUDU’s South Asian members launched the South Asian Committee (SAC) to organize and resist drug laws, to challenge the racist neglect in the state’s response to the toxic drug crisis, and to advocate for the expansion of culturally appropriate services.

When SUDU hosted a temporary pop-up overdose prevention site, SAC member Harnek Bal noted, “The deaths and struggles of South Asian people who use drugs have gone largely neglected in this eight-year-long public health emergency.”

SUDU board directors Pete Woodrow and Gina Egilson at SUDU’s pop-up inhalation overdose prevention site tent in July 2024. Photo courtesy of authors.

Bal also says, “In addition to the complete lack of services in Newton, there is a broader issue of a lack of cultural safety and effort to overcome language barriers to save lives across all types of existing services.”

SAC meets weekly with discussions facilitated in Punjabi, and members include people with varying citizenship status, including migrant workers and international students.

In building a platform for South Asian people with lived and living experience of drug use, SAC has grown into a strong example of community organizing, and can be used as a blueprint for a more inclusive harm reduction movement.

Onward together

“It’s not the institutions that push these policies forward, it’s the people,” says Nesa Hamidi Tousi, a nurse practitioner in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, adding that many organizations must remain accountable to funders, and that individuals working in the sector, have a responsibility to contribute to external, multi-tiered, and grassroots organizing to build a more equitable world.

“Approaching it more from a community lens is a good place to start,” adds Hamidi Tousi. They point out that organizations invested in the status quo can end up undermining visions of a movement if they are allowed positions of leadership.

“Non-profits were created for counter-insurgency,” agrees Kassir, who pragmatically admits that while non-profits will not drive transformation, they can be useful tools for incremental steps and finding people with shared values with whom to build solidarity.

For Kassir, Hamidi Tousi, SUDU’s SAC, and many others involved in rebuilding community networks of care, understanding the limits of the nonprofit and health-care sector roles in transforming society, and instead organizing outside of them to apply pressure, is an important component in reducing violence and driving change.

As Hamidi Tousi observes, “We divide interventions into multiple phases, upstream versus downstream” but to address violence, “you gotta go to the root, the water source.”

* Robin is a pseudonym used for safety and confidentiality reasons.