Until recently, my partner lived in a rent-subsidized studio apartment in Greenwich Village. Her room, which I shared as often as I could, was kitty corner to the ten-story Brown Building, which in the early 1900s housed the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory on its top three floors. The owners of the factory, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, habitually locked the doors to the stairwells to halt theft and increase productivity. On March 25, 1911, a fire swept through the factory. The locked doors trapped the workers inside and 146 people, most of them women, died from burns or smoke inhalation. Some leapt to their deaths to avoid being burned alive. On the anniversary of the tragedy, local labour activists gather to remember the dead and affirm their commitment to ending work-related death and injury.

One day when I was still a teenager, my dad came home early from work. In those days, he installed aluminum siding on new houses in Calgary’s suburbs, working on scaffolding 20 or 30 feet above the ground. “A man died at the job site today. He was working on the roof when he slipped and fell,” he said, a tremor in his voice. “His son was working with him. He held his father’s hand as we waited for the ambulance.”

Several years later, I began working with my father. By then he was working on his own as a finishing carpenter. We would arrive after the framers, electricians, and plumbers had come and gone. We hung doors, installed baseboard, and built cabinets and floor-to-ceiling entertainment units. During our coffee breaks we sat in companionable silence, side by side against the dusty drywall, surveying the fruits of our labour: the building’s daily transformation.

I would leave the job site with sore knees, with bruises and small scrapes on my elbows, and cuts on my hands and arms. But still, I thought, it wasn’t bad. I was making good money. We worked inside, never more than a few feet above the ground.

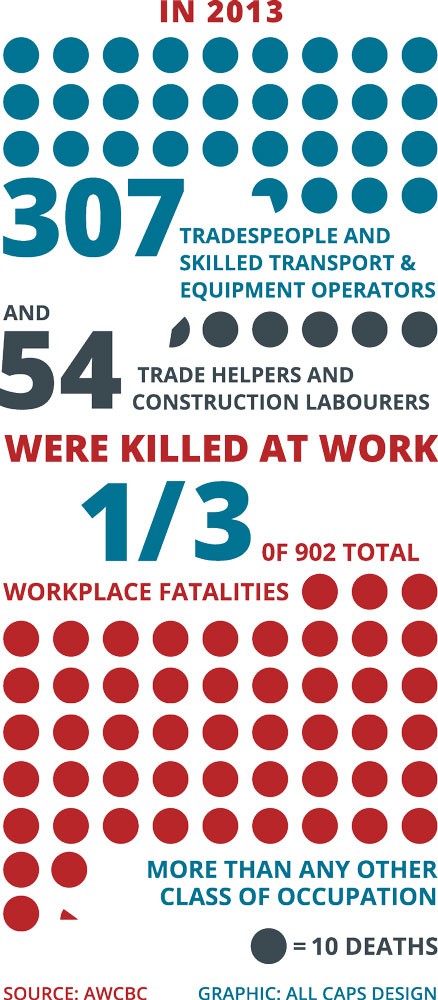

In 2013, 307 tradespeople and skilled transport and equipment operators in Canada were killed at work. A further 54 trades helpers and construction labourers suffered fatal job-related injuries. Together they accounted for more than one-third of the 902 workplace fatalities in Canada that year, more than any other class of occupation for which the Association of Workers’ Compensation Boards of Canada keeps statistics.

In Alberta, 346,160 people worked as skilled tradespeople or labourers in 2011 (the most recent statistics available). Sixty-two workers (48 skilled workers and 14 labourers) died on the job in 2013 in that province. Ontario had slightly more than twice the number of people – 805,495 – employed as skilled tradespeople or labourers in 2011, and in 2013, 107 were killed at work. It’s dangerous to work in construction; even more so in Alberta. Perhaps it’s the pressure of a booming economy: inexperienced or poorly trained workers being pushed into work for which they aren’t prepared, employers flouting safety regulations for reasons of cost or expediency, bosses pushing workers to move faster.

“Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred,” Rose Schneiderman told the crowd at a protest meeting on April 2, 1911. As one who devoted her life to organizing her fellow garment workers, her words still resonate more than a hundred years later.

Today, though, unionization rates are falling. In 1981, Canada’s unionization rate was 38 per cent; today it is 30 per cent. Alberta’s rate of unionization is the lowest in the country: 22.8 per cent. At 20.2 per cent, the unionization rate in the construction industry in Alberta is the third highest among private-sector industries, after utilities (at 50 per cent) and transportation/warehousing (29.7 per cent). CUPE represents workers at several municipally owned utility companies, accounting for the elevated rate of unionization in that industry.

The new houses I helped to build in Calgary’s mountain-view suburbs and moneyed inner-city neighbourhoods were built by upscale developers who employed tiny crews of subcontractors to do the work. Most weren’t unionized. To be eligible for union membership, a tradesperson must apprentice. The apprenticeship period includes over 1,300 hours of on-the-job training and eight weeks of technical training each year for a four-year period. Like many tradespeople, my dad, who had started working in home construction before I was born, did not have a journeyman ticket. For many, the work paid well enough without it.

The Building Trades of Alberta (BTA) represents 75,000 skilled workers from 21 affiliated trade unions. These workers tend to work on larger developments, including commercial and industrial construction jobs across the province, from the new office towers of Calgary to tarsands infrastructure. Part of the BTA’s core mandate is to “ensure that [their] members are working in the safest conditions in Alberta.” Alberta, which has a lower rate of unionization than Ontario, does have a higher rate of workplace fatalities, but a causal relation between unionization and workplace death rates can’t be proven using available statistics.

Schneiderman finished her 1911 speech by saying that it was “up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.” Two years prior, she had helped lead the Uprising of the 20,000 – the largest strike by American women workers up to that time. The strike lasted 11 weeks and most of the workers’ demands were granted, including a 52-hour week, holidays with pay, and negotiation of wages with employees.

The Alberta Regional Council of Carpenters and Allied Workers boasts on its website that it has not had a strike in more than 30 years. “Strikes help nobody,” says the union, which represents 12,000 men and women working as carpenters, millwrights, and other tradespeople. “Least of all working people who suffer the loss of income.”

Unionized tradespeople do have higher incomes than their non-union counterparts. In December 2014, the overall hourly wage for tradespeople in the province was $28.97. Unionized carpenters in Calgary and Edmonton made $41.53/hour, electricians were paid $46.80, bricklayers $36.67. General labourers made the least of the unionized construction workers, earning $35.24, still above the average for tradespeople in the province.

In Alberta today, the unions that represent tradespeople see their members’ fortunes tied to those of the developers and industry. The BTA mandate underscores the development of long-term working relationships with owners, and their aim to “secure new investment in Alberta.” On the job site, many workers (unionized or not) have a similar perspective: at the height of Calgary’s boom years in the mid-2000s, when work was consistent and skilled carpenters were in high demand, my dad made enough to place him firmly in the middle class for the first time in his life.

Residential home construction is big business, especially in booming Alberta. According to the Canadian Home Builders’ Association, the lobby group for residential developers, the industry generates $17.9 billion in investment. Their report claims that the industry creates 125,100 jobs, which generate $7.9 billion annually in wages annually. As their release boasts, “across Canada, that means 906,000 jobs, $49.7 billion in wages and $120.4 billion in investment value.”

The rise in house prices since 2000 has generated $1.7 trillion in net new wealth for homeowners. In addition to a place to raise their families and live their lives, Canadians see their houses as investments. Nearly 20 per cent of Canadians are depending on the value of their home to finance their lives after retirement.

At the time of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire, the garment industry was the centre of New York’s economy, with three times the value of sugar refining, the city’s second largest industry. Unlike garment factories, which could (and did) move to the countries with the cheapest labour and production costs in order to increase owners’ profits, homes are built in place. But profits are not as dependable as a well-poured foundation; the work that pays today cannot be counted on to be there tomorrow.

In 2007-2008 a crisis occurred in the housing markets of the United States, Ireland, and Spain. Because speculators could purchase houses and then refinance them for a profit based on the appreciation in market value, the house had become “a convenient cash cow, a personal ATM machine,” in the words of Marxist author David Harvey. Then the bubble burst. An estimated 10 million people lost their homes in the U.S. through foreclosure, with African Americans twice as likely as white Americans to be forced from their homes. The crisis rippled through the economy. Employment in Canada’s construction industry suffered a nine per cent drop. My father lost his job. The housing developer for whom he had worked consistently for the last 10 years couldn’t use his skills. Their clients’ investments had taken a hit; new luxury homes would have to wait.

I haven’t worked as a carpenter in many years. For the past few years, instead of building new houses, I’ve earned a wage organizing tenants to fight for improvements to their own homes. I’ve moved to another province. When I speak to my dad, work is a constant theme: a friend of a friend may have a small renovation job, someone from church says she wants to build a deck in her backyard. He picks up these jobs when he can, to supplement his wages. He works in a factory that supplies eavestroughs for industrial buildings. It’s not unionized labour. When he describes the metal-shaping equipment I worry about the possibility of injury, picture mangled bones and blood on the factory floor.

My partner had to leave her Manhattan apartment; she found a one-bedroom in Brooklyn, 45 minutes and two subway trains away from work. I hope my parents visit; I want to show my dad the old neighbourhood and the old Shirtwaist Factory. I want tell him about the fire, about the bosses, about Rose Schneiderman and the movement of which she was a part.