The dream of a benevolent welfare state may live on in social work theory, conference papers and mission statements, but as far as front-line bureaucracy goes, welfare is dead. Only its image remains, as faint as chalk on a sidewalk. No longer even pretending to be a right or social safety net, social assistance has mutated into a series of manipulative tactics to prod and intimidate its clients into jobs that no one wants. In other words, welfare has become workfare.

While welfare, or social assistance, has long borne the official stamp of benevolence, a new state-prescribed client status has come to undermine and replace the far stronger status of the citizen. As clients, we have the “right” to submit our polite requests to the proper authority using the prescribed channels or to purchase our unequal rights in the marketplace. Should we meet the eligibility criteria or find a sympathetic ear, we might just win some minimal assistance. If not, well, all is fair in markets and bureaucracies.

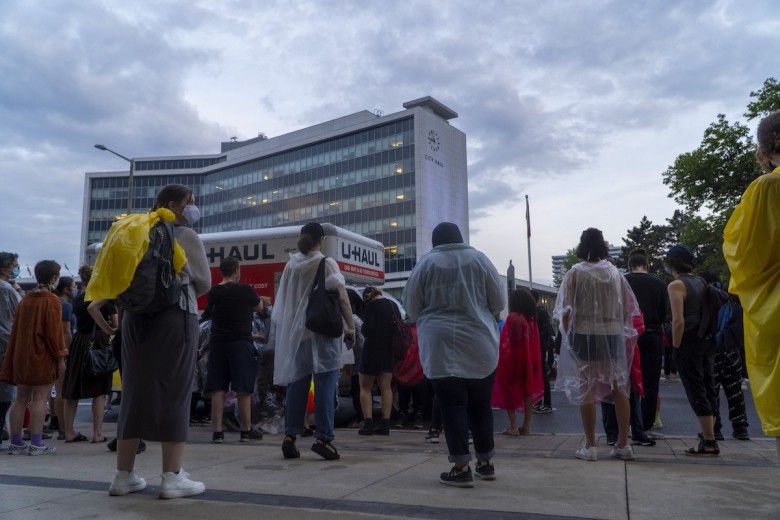

In fact, the right to income assistance is now so imperilled that advocates with legal training, some of them actual lawyers, are routinely needed to help applicants navigate ministry policy and procedures and to hold governments accountable to their own legislation. Advocacy organizations such as the Together Against Poverty Society in Victoria and the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty are sometimes all that stand between many applicants and life on the streets. Appeals to human rights now come into play only in rare instances where a Charter challenge is invoked in the courts.

Welfare policy has long sought to instill incentives to work through a mix of positive and negative consequences, termed “carrots and sticks” in welfare reform circles. In the free trade era of capital mobility and fierce international — and even inter-regional — competition, however, income assistance policy has become subservient to labour market and business demands, with a decided preference for sticks.

Having deemed labour market conditions and job creation to be the rightful jurisdiction of business, government has assumed the minimal role of motivating precarious workers to accept the new norm of part-time, insecure, boring and hazardous jobs.

From welfare to workfare

The demise of welfare in favour of this workfarist ethos, which is based on discipline and control, has been achieved both incrementally and through a series of onslaughts. The elimination of the Canada Assistance Plan in 1996, which had set federal standards for welfare provision and provided dedicated funding for income assistance, opened the doors to regional experimentation with methods for enforcing work obligations on welfare recipients and reducing caseloads.

Early experiments following the dissolution of the Canada Assistance Plan included service and rate cuts, such as the drastic 22 per cent reduction of income assistance under the Mike Harris government in Ontario; restrictions on eligibility, such as the three-month residency requirement attempted by British Columbia’s New Democratic Party; and an uneven array of workfarist schemes ranging from work-for-welfare placements to training wages and employability contracts. New layers of surveillance have also been added, including special welfare fraud units such as those introduced by Alberta’s Conservatives and B.C.‘s NDP.

Provincial governments have also sought to reinforce work obligations by rewriting eligibility criteria and reclassifying recipients. In 2001, for instance, the newly elected B.C. Liberals undertook a full-scale review and re-classification of disability status so as to disqualify and reduce benefits to existing clients and discourage new applicants. They also placed two-year time limits on income assistance and ramped up efforts to deny, reduce and recover benefits under the guise of policing welfare fraud. Austerity measures, exhaustive rules and extraordinary scrutiny are all part of a broad strategy to make eligibility so onerous as to wear people down with tedium and obstacle.

While dedicated fraud units send the message that illegal behaviour is rampant among recipients, historical rates of welfare fraud run between one and three per cent, which is lower than fraud rates for every other income bracket through the income tax system. Further, fraud in this arena refers to any situation in which a rule is breached, even if by misunderstanding or administrative error. These units do, nonetheless, perform a unique role in intimidating recipients who can be investigated at the ministry’s whim. The hype over welfare fraud, including the use of Crime Stoppers to generate community complaints, has succeeded in associating income assistance with criminality.

With a few exceptions, the undoing of income assistance persists. In a recent round of incremental cuts effective June 2010, the B.C. government is no longer covering dental, diagnostics or birth control for persons receiving income assistance and disability benefits, while Ontario has eliminated dietary allowances for persons with specific nutritional needs.

Desperate and disciplined

Too often this passage from welfare to workfare is read only as an erosion of entitlements and not as an assault on labour. As a significant engine of productivity and growth — and by growth I mean profit — work-ready (desperate and disciplined) labourers are a highly valuable commodity, a main ingredient that enterprising cities require to compete for transnational business.

Workfare regimes thrive on divisions among subclasses of workers, exploiting centuries-old distinctions between the deserving and undeserving poor. Where some client groups, such as those with disability status, receive slightly higher benefits and some reprieve from work-seeking activities, others are isolated to receive harsher penalties, mandatory work requirements and lower assistance rates, as in Saskatchewan’s Transitional Employment Allowance and B.C.‘s Training Wage, a sub-minimum wage for youth and new entrants into the workforce. The instability of the labour market further frustrates any sense of common cause among those whose economic standing is in flux and insecure.

Such ill treatment is bolstered by a classed view of human nature and human value, one that uses racism, sexism and xenophobia — anything it can get its hands on, really — to isolate and disparage targeted groups. If news blogs are any measure of public sentiment, pro-business and anti-poor lobbyists have effectively enlisted many working- and middle-class folks to do the dirty work of devaluing low-income persons.

While the affluent are said to respond to positive incentives such as less regulation, unrestricted earnings and affirmation, the poor are thought to need the spurs of over-regulation, penalty and insult. Those who receive the least are the most answerable, not just for their conduct, but also for the risks and failings of the economy, be it the public debt, lags in productivity or a lack of competitiveness.

The same working-class identity that attaches pride to work as a basis for self-valorization and solidarity easily becomes a weapon against anyone who cannot claim this esteemed status. That is why, while using every available means to claim services using current social assistance legislation, there is a pressing need to confront the attachment of moral superiority to work and to scrutinize the costs associated with “productive” employment in a capitalist economy.

The case for a guaranteed income

A guaranteed minimum income, aptly dubbed a Liveable Income for Everyone (LIFE) by anti-poverty activists in Victoria, may be poised to offer us greater control over our labour while underlining every person’s right to share in the benefits and remaking of this earth. A 2009 research report by Jim Mulvale and Margot Young for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives presents the idea’s recent history, along with possible models, their drawbacks, advantages and costs, and serves as a good primer for anyone wading into this policy area for the first time.

In its strongest version, a guaranteed income grants every person living in a defined region a basic adequate income without work conditions or restriction on earnings, savings or resource sharing. Earnings can be taxed back above a designated income level and at progressively higher rates as income goes up.

Concerned that a guaranteed income could become another economic ghetto, some social justice activists promote good, full-time jobs and a strong social safety net as preferred anti-poverty measures. Not a redesign of the economy or society, a guaranteed income is a modest intervention that coalesces with movements for living wages, work-life balance and a shorter work week. It is not a stand-alone fix, nor is it a replacement for job creation, just as job creation is incapable of providing an adequate income for everyone.

That being said, a guaranteed income has the potential to address several major flaws with current income assistance. Most directly, it removes the limits on allowable earnings — typically set at $50 to $100 per week, after which income assistance is clawed back — that trap people between poverty-level income assistance and poverty-level wages. Because a guaranteed income is given to everyone, the under- or unemployed are not singled out for scrutiny and resentment. Work still carries its usual rewards — extra income, esteem, participation, belonging, creative outlet and so on — minus the class-specific penalties and manipulations.

Central to the workfarist mentality is that income assistance rewards non-work. Yet there is abundant evidence all around us that people need no special prodding to engage in socially product-ive pursuits. Furthermore, our definition of work is beset with many chronic problems. Much work does not count as employment, and work and employment are often disconnected from income level. Most wealth accumulation today is not gained in exchange for labour or in the real economy, but through speculation in financial markets. In contrast, under capitalism’s waged division of labour, motherhood has so far proven no match for the great social contributions of junk mail and warfare.

Critics of a guaranteed income also charge that it is too expensive. But poverty, too, is linked to a host of costly consequences. A raft of research connects poverty with ill health, increased risk of injury and violence, emotional trauma, incarceration, addictions, family disruption and foster care. Policing, prisons and emergency services are generally more costly than social and educational supports, not to mention the loss of human potential and needless suffering.

The capitalist economy, with its spread of part-time, temporary and low-paying jobs, is signalling the decline of standard full-time employment. Rather than fighting for a return to a past standard of full-time, lifelong jobs, we have an opportunity to embrace a new norm of work in which the market is not our sole source of income.

Even where it has been possible, in our weakened state as clients, to squeeze minor reforms out of a begrudging bureaucracy, the best result to date has been slightly less poverty. Welfare’s vast reserve of other faults has remained intact, including the privileging of an administrative class to exercise an inordinate amount of control in people’s lives. A guaranteed income might not be the last struggle to emancipate our labour, but it would be a step away from a wage system that was, after all, invented by the capitalist class.

Expecting the decades-old fight for progressive welfare reform to produce vastly different results is at least as unrealistic as a guaranteed income.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)