Plain language summary (What is this?)

- Although Canada is seen as a peaceful country, Canada uses its military to accumulate power and profit at home and abroad. Some of our major political parties support the growth of our military, but doing so is incompatible with disability justice.

- Jasbir K. Puar, the author of a book called The Right to Maim, tells us that many disabilities in the world come from war. This also means that most disabled people live in Latin American, African, and Asian countries.

- People in wealthier and whiter countries like Canada often overlook disabled people elsewhere, but disability justice advocates work to make sure their experiences are known, too.

- Imperialist states like Canada, the U.S., and Israel have a long history of killing and disabling civilians, harming the natural environment, and making money from war. This continues today.

- These states target their violence at some groups of people more than others. Black and Indigenous people in Canada and the U.S. are most likely to be disabled, jailed, and houseless because of this.

- Many disability justice supporters protest these experiences and are finding new ways to live that don’t require the existence of police, prisons, and war.

Despite the national myth that portrays Canada as a champion of peace, our lives in this state are deeply impacted and influenced by war and militarism – from the Canadian Armed Forces illicitly spying on Black Lives Matter protesters to Canadian authorities taking advantage of the 2009 military-backed coup in Honduras to open the country up to Canadian mining interests.

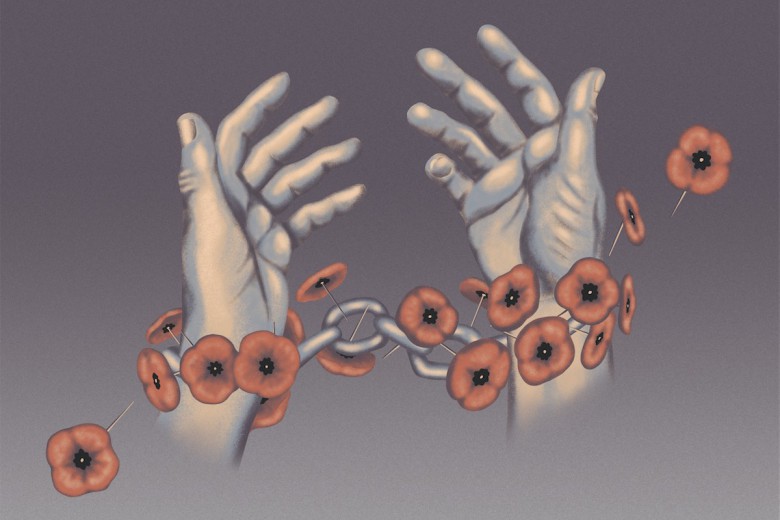

While the federal Liberal government announces billions in new military spending each year, we seem locked into a future of war – but this future is incompatible with disability justice. In the preface of her book The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability, scholar Jasbir K. Puar writes that “the production of [much] of the world’s disability happens through colonial violence, developmentalism, war, occupation, and the disparity of resources.” To ensure the liberation of disabled people, disability justice advocates near the heart of global imperialism must oppose war and imperialism.

Rethinking disability, debility, and capacity

In Canada, $24.3 billion in public money went toward the military in 2021. This money is spent on everything from “counter-terrorism operations” in the Middle East to the research and development of new weapons, to “sovereignty patrols” in Canada’s Far North. Though the Canadian state says its military exists “to protect and defend Canada,” it’s often the aggressor, using the military to extend its influence and accumulate profit at home and abroad. This includes providing important support to the largest imperialist power and military spender in the world, the United States. Canada – like the U.S. – is an imperialist power and one that generates and profits from disability.

In The Right to Maim, Puar explores how certain bodies are at greater risk of becoming disabled than others – particularly through imperial violence – and what happens when the material conditions to reframe disability as a positive thing are not available.

“Living with disability and debility is highly organized by the kinds of access to privilege that you have,” Puar explains to me in an interview. “I think about capacity not only as something that’s bodily – it’s also about the kinds of health care, social support, material resources, and care networks available in your life.”

And the scale of debility is enormous: in 2016, the World Health Organization estimated that as part of the Syrian war, 30,000 Syrians were being injured each month.

Puar further distinguishes between disability and debility: disability might be a political-relational identity, while debility is a process. One is debilitated by repeated exposure to harm and violence – a wearing-down of the body and mind throughout one’s life. This could look like the mercury accumulating in the bodies of Indigenous peoples whose water source has been polluted, or panic attacks due to daily encounters with racism in education, health care, and justice systems. What this tells us, Puar says, is that “it can be productive for the settler colonial state to keep some populations alive but in a space of continual, perpetual injury.” And the scale of debility is enormous: in 2016, the World Health Organization estimated that as part of the Syrian war, 30,000 Syrians were being injured each month.

“Disability,” Puar continues, “becomes the [way] institutions exceptionalize injury or the non-capacitation of a body.” This means that institutions view disability as something out of the ordinary instead of the inevitable outcome of living under oppressive conditions, and they place onus on the individual for being disabled, rather than on these oppressive systems for disabling the individual.

Though a minority of disabled people live in the Global North – the wealthy, imperialist countries like the United States, Canada, and those in Western Europe – Puar notes that Global North disability rights advocacy tends to focus on disabled people attaining equality more than halting and holding accountable the systems that produce disability throughout the rest of the world. She writes that disability rights advocacy asserts “that disability should be reclaimed as a valuable difference […] through rights, visibility, and empowerment discourses […] rather than addressing how much debilitation is caused by global injustices and the war machines of colonialism, occupation, and U.S. imperialism.”

“Disability, becomes the [way] institutions exceptionalize injury or the non-capacitation of a body.”

In other words, Global North disability rights appeal to the state to protect mostly white and wealthy disabled people. But Puar reminds us that disability and disablement can be a purposeful goal of the state. In contrast, a disability justice framework helps us understand that the safety of some disabled people in the Global North must not come at the expense or production of disabled people in the Global South. Disability justice, a movement founded by racialized people, explicitly denounces imperialism and recognizes that, in the words of disability justice collective Sins Invalid, “Disabled people of the global majority – Black and brown people – share common ground confronting and subverting colonial powers in our struggle for life and justice.”

Debilitation in action

There is a careful balancing act that imperialist nations must perform when waging war in order to appear more humanitarian. One strategy is to simply understate the death toll. For example, in July 2016, the U.S. performed an air strike – an assault that is purportedly “surgical” in accuracy – on Tokhar, Syria, and claimed that between seven and 24 civilians were killed. An investigation by the New York Times later found that at least 120 civilians had been killed.

When people are killed on a larger scale, and mass numbers of death can’t be overlooked, Puar writes that the creation of disability becomes “a tactical military move.” For example, during the 2018-2019 Great March of Return at the Gaza border, Israeli snipers intentionally maimed thousands of Palestinians by shooting them in the lower thigh or back of knee. There, one bullet can damage nerves, arteries, and the knee joint, and can lead to bacterial bone infections. So many Palestinians were injured that Gazan hospitals ran out of beds and were forced to discharge patients early.

“By creating a humanitarian catastrophe, Israel is able to reframe the global debate around the rights of the Palestinian people in the Gaza Strip from that of national liberation and anti-apartheid struggle to one of the medical needs of an afflicted population,” wrote Puar and Ghassan Abu-Sitta in Al Jazeera. “The need to provide for a large number of disabled people further entrenches modes of dependency on aid.”

Through these methods, states can announce that no one has been killed – that is, in the absolute present, the right-here-and-now – and also gain the profitable opportunity to rehabilitate injured civilians.

War also takes a toll on the natural environment, which can kill or disable civilians. During the Vietnam War, U.S. military forces weaponized “tactical herbicides” – primarily one called Agent Orange – in order to expose North Vietnamese guerrilla forces who hid within forests and to reduce their food supply. Nineteen million gallons of herbicide were sprayed from helicopters, trucks, and boats, defoliating millions of acres of forests and farmland and accumulating in the soil. This pollutant is linked to disabilities including cancer and diabetes, with one study finding that those living in exposed areas in Vietnam are more likely to bear children with spina bifida.

Other ostensibly non-lethal methods are used by states to maim and injure populations. In Indian-occupied Kashmir, the Indian army suppressed Kashmiri protests with lead pellets – also known as “birdshot” – which embedded themselves in the eyes of hundreds of protesters, causing permanent blindness. At Standing Rock, security and police used water cannons, sound cannons, chemical agents, and other munitions against land defenders, resulting in hundreds of injuries that included broken bones.

Through these methods, states can announce that no one has been killed – that is, in the absolute present, the right-here-and-now – and also gain the profitable opportunity to rehabilitate injured civilians. In Gaza, Israel has made a profit from reconstructing the same health-care infrastructure it destroyed and filling those hospitals with maimed Palestinians, only to destroy and rebuild again.

Conveniently, when the numbers of those killed are tallied and publicized in the media, as Puar writes, “the dying after the dying, perhaps years later, would not count as a war death.”

Who are the targets?

In countries like Canada, disability rights activists often say that everyone should be involved in disability advocacy because anyone can become disabled. And while this is true, when we dig deeper into disability and debility, we begin to understand that the people most likely to be disabled are those oppressed by the ruling class and the state. Today, Indigenous peoples are the most likely to be disabled in Canada and the U.S., followed by Black people in the U.S. Both groups are also disproportionately incarcerated and unhoused. These statistics are the historically seeded outcomes of U.S. and Canadian imperialism.

In the Global North, we often have the false impression that war is something that happens abroad, waged in places like Afghanistan, Libya, and Vietnam. But it happens at home too. European colonizers fought wars against Indigenous peoples protecting their homelands in what came to be known as the U.S. and Canada. The Canadian and U.S. militaries are still heavily involved in brutalizing Indigenous land defenders at places like Standing Rock and Wet’suwet’en territory, in order to enforce resource extraction.

Today, Indigenous peoples are the most likely to be disabled in Canada and the U.S., followed by Black people in the U.S.

Across the globe, disabled, racialized, Indigenous, queer and trans bodies exist on borrowed time in the eyes of the state. These bodies are available to be continuously crippled for profit or made an example of through death – like how Black people are over-policed and publicly executed by officers in Canada and the U.S.

This “sanctioned maiming,” Puar writes, highlights “a profound failure in the global human rights framing of disability as a protected and supported social difference – protected and supported unless it is part of the war tactic of a settler colonial regime.”

In the belly of the beast

When Puar and I speak, I am in Canada and she is in the U.S. “We are in the belly of the beast of that empire,” she tells me. “Imperial power produces disability everywhere, all over the globe in different kinds of ways through forms of militarization, occupation, capitalist exploitation, dispossession.”

In the face of this, the disability justice movement in the Global North must work to oppose war, militarism, imperial violence, and debilitation. Puar gives the example of the Abolition and Disability Justice Collective which, she says, “recognizes the connected carceral infrastructures, that settler colonialism here supports settler colonialism there.” In 2021, as Israeli airstrikes landed in the Gaza Strip, the group released a statement of solidarity with Palestine, writing that “Israeli settler colonization is a disability justice issue that underscores the urgency of abolition and its internationalist dimensions.”

We have been taught to see war as a conflict that comes to a head through physical, chemical, or nuclear altercation in a country far away. In actuality, we are part of the constant cycle of war and militarism – be it police brutality, colonial occupation, or military expansion under the guise of “humanitarian intervention.” This is what some scholars have called “perpetual war”: the constant growth of military powers, meant to sustain endless fights against nebulous enemies such as “terrorism.”

Here, many disability justice, anti-war, and penal abolitionist organizers are already fighting against the military-industrial complex and advocating for peace and community-based safety.

“One of the things that the War on Terror has really shown us is that war doesn’t ever need to end – it’s actually something that’s sustainable, and it’s profitable,” Puar tells me. “War isn’t a simple relationship between one side and the other, but a multiplayer, proxied [event] that has numerous economic and ideological and political relations embedded in it. […] What it means to focus on maiming along with killing means actually to understand war differently, in some sense – because it’s a kind of ongoing bodily assault.”

Resisting war, militarism, imperial violence and debilitation must begin at the grassroots level. Here, many disability justice, anti-war, and penal abolitionist organizers are already fighting against the military-industrial complex and advocating for peace and community-based safety. Supporters of disability justice displace the need for police and military by practising unarmed civilian protection, from Minnesota to South Sudan; campaigning to defund, demilitarize, and abolish the police; protesting against weapons deals and manufacturers; calling for reinvestments in social services and health care; and advocating for returns to Indigenous models of justice, among other things.

In Puar’s words, it is a fantasy “that resistance can be located, stripped, and emptied,” whether from the land or the body. The world that disability justice advocates aim to create centers co-operation, community, and the dignity of those most marginalized – a world that cannot be achieved through the endlessly violent cycle of war.