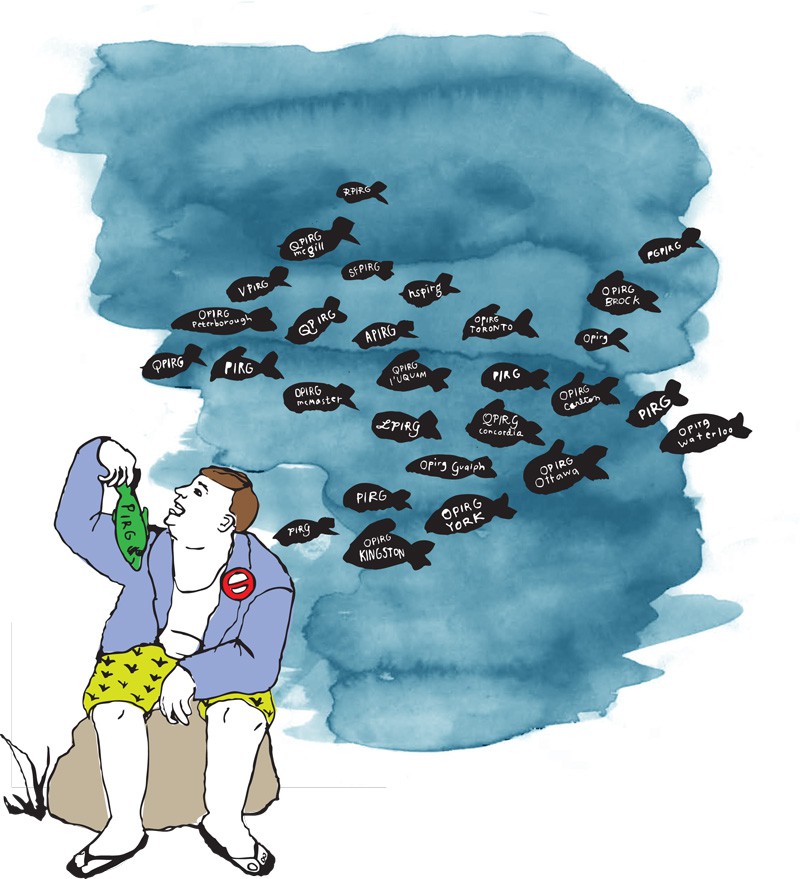

In the fall of 2011, conservative students at Queen’s University in Kingston launched a campaign to defund their campus’ Public Interest Research Group (PIRG). In anticipation of a mandatory 2012 student referendum to renew the Kingston PIRG’s $4 undergraduate levy, detractors started a Facebook page encouraging students to opt out of the levy. They adopted the recurrent “NoPIRG” campaign name, targeted PIRG staff and volunteers with defamatory rumours, and criticized the organization for funding initiatives that “don’t reflect the values of the entire community” – as though values are ever unanimously endorsed on a post-secondary campus. The strategy worked. On February 1, 62 per cent of Queen’s students voted to revoke the 20-year-old levy.

With its remaining $4.36 graduate student levy and some financial equalization revenue from the Ontario PIRG provincial network, the Kingston PIRG will maintain operations for one year and campaign to reinstate the lost funding stream in 2013. Nevertheless, the Kingston loss is the most severe student-led blow against the PIRG network in its almost 40-year history. It also marks a significant victory for a rising group of right-wing populists with roots in the Ontario Progressive Conservative Campus Association (OPCCA).

The OPCCA gained notoriety among PIRG supporters in 2009 when it hosted internal, full-day strategy workshops on several campuses to discuss how best to take over student unions and, in one particular session, how to “challenge and defeat the PIRGs.” A clever infiltrator uploaded an audio recording of one workshop to WikiLeaks, and student media picked up the story. Student union representatives and PIRG supporters were understandably irked by OPCCA’s sober tactical deliberations about establishing smoke-and-mirror front organizations and building tactical alliances on controversial issues – “If Norman Finkelstein comes to campus … get [the Jewish students’ association] involved … if it’s a radical feminist who’s very pro-choice, [your allies are] going to be the pro-life people on campus” – and, above all, targeting PIRG funding streams with careful populist messaging about alleged misuse of students’ money. Winning defunding referenda and “getting [PIRGs] off the fee statement,” explained one OPCCA facilitator, “should be the ultimate objective.”

The anonymous WikiLeaks activist criticized the workshop series as conspiratorial, and several campus newspapers reiterated this charge. In particular, progressive student activists decried the participation of Conservative politicians like Kitchener-Waterloo MP Peter Braid (who delivered the keynote at the OPCCA workshop that was posted on WikiLeaks), alleging that the PC party was attempting to “interfere with student governance and undermine non-profit organizations.” NDP MP Niki Ashton implied something similar when she asked the House of Commons: “Does the government condone the overthrowing of democracy on campuses by the Conservative Party?” For the former Ontario chairperson of the Canadian Federation of Students, Shelley Melanson, the workshops amounted to political party involvement that “violates student election policies.” This characterization stuck. In an important article about the struggles the PIRG at McGill faced with similar attacks in 2011, the McGill Daily reiterated warnings of an “anti-PIRG campus conservative conspiracy.”

To be sure, the WikiLeaks recording confirms that OPCCA organizers intend “to bring people into the party” (though they have since downplayed both their links to the PC party and the peculiarity of a federal politician taking time to speak to a dozen rookie undergrads). However, while allegations of conspiracy might have provocative tactical value for PIRG supporters in the short term, they’re ultimately distracting. To whom are we appealing when we dub the conservative strategy suspicious or unfair? Moreover, to what norms of fairness under Canadian democracy do we hope to appeal?

As PIRGs enter what will likely be a period of escalated attacks, it’s worthwhile to reorient to the basic truths underlying conservative platitudes. OPCCA executive committee representatives aren’t hiding anything when they recount how “the training sessions brought together groups of small ‘c’ conservatives in an effort to encourage involvement on campus.” They’re not conspiring; they’re organizing. Their anti-PIRG ambition is part of an explicit strategy to bring grassroots legitimacy to the conservative movement and to train their youth members. The problem is not that the OPCCA has defied “democratic” standards; the problem is that their plan is working. And PIRG supporters should prepare for the fight.

The “Blueprint”

In 2002, Queen’s undergraduate and then-OPCCA president Adam Daifallah accidentally disclosed the existence of the controversial Millennium Leadership Fund (MLF). Founded in 2000 with donations from senior members of the Ontario Progressive Conservatives under former premier Mike Harris, the MLF “helps defray costs for conservative university students in their bids for election” to student government. In an unintentionally public email, Daifallah congratulated MLF recipients for their victories at the University of Windsor, the University Western Ontario, and the University of Waterloo. The recipients included then-OPCCA vice-president Ryan O’Connor, who facilitated the leaked 2009 anti-PIRG workshop. Despite denunciations by student representatives, the MLF was never formally investigated or disallowed. In 2003, it was used to help the conservative Progress Not Politics (PNP) slate take over York University’s undergraduate student union.

Under its populist banner, PNP brought together conservative activists and members of the now-defunct Young Zionist Partnership. Once in office, PNP hired OPCCA’s O’Connor as a policy analyst and cut funding to what they called “specialty groups,” including the Black Students’ Association; Aboriginal Students’ Association; and Trans, Bisexual, Lesbian, and Gay Allies at York. They also eliminated the vice-president of equity and services executive position, organized pro-war campus events, endorsed the Conservatives’ “income-contingent loan repayment” strategy, and postponed elections for two semesters to keep themselves in office.

But their victory was fleeting. Compounded by campus anti-war and labour mobilizations, and a widely publicized lawsuit against York’s sitting president who had unilaterally expelled a Palestine solidarity student activist, PNP’s recklessness galvanized the campus Left. Students voted out PNP at their first opportunity, and conservatives haven’t managed a comeback.

Since then, OPCCA has reoriented to more sympathetic campuses like Waterloo and Queen’s and taken sharper aim at the PIRGs – an institutional opponent that, according to vocal OPCCA member Aaron Lee-Wudrick, “at least in theory, can be defeated.” During the WikiLeaked workshop, Lee-Wudrick and O’Connor described their anti-PIRG manoeuvres at the University of Waterloo in 2002 and 2005 when they nearly forced a referendum on the PIRG’s levy. The referendum, which they “orchestrated behind closed doors,” was cancelled due to multiple campaign infractions. Nevertheless, the experience was instructive and inspired others to launch anti-PIRG campaigns at Simon Fraser, Dalhousie, Carleton, McGill, the University of Toronto, and Queen’s.

Because of a growing infrastructure devised to train the next generation of conservative youth, OPCCA strategy has improved over the last decade. Having come far since his MLF blunder, Daifallah is one of this infrastructure’s biggest proponents. Now writing for the National Post and working for Hatley Strategy Advisors (a Montreal-based consulting firm he co-founded in 2009), he’s an up-and-coming pundit. In 2005, he and the former president of the now-defunct PC Youth Federation, Tasha Kheiriddin, co-authored Rescuing Canada’s Right: Blueprint for a Conservative Revolution, a strategy bestseller that – despite the titular oxymoron – was enthusiastically endorsed by Mike Harris, Mark Steyn, and Preston Manning.

Blueprint outlines an ambitious strategy to build an extra-parliamentary “ideological infrastructure” to “professionalize” conservative politics in Canada. Although Stephen Harper’s 2006 federal victory made much of the Blueprint’s sentiment outdated, the book remains useful since, as one critic explained, it is “remarkably frank about the goals of the new ‘conservatism,’ and it is almost disconcertingly honest about its tactics.” In detail, the authors recommend emulating the U.S. conservative movement by “rebalancing the media,” confronting the “blight on academia,” and “seeding a thousand think-tanks to develop … policy and counter the propaganda of the left.”

Kheiriddin and Daifallah also insist that youth are “the heart of the conservative revolution” and urge for the proliferation of conservative campus organizations using the U.S. strategy – “evangelize and convert! … get ‘em while they’re young” – to which they attribute the explosion in such groups from 400 in 1999 to 1,100 in 2005.

In 2008, the Edmonton Journal noted a “resurgence” of conservative campus clubs in Canada. Now with a clarified network of mentors, OPCCA has regular access to strategy advice. And their teachers earn their stripes. One such mentor, Richard Ciano, co-founded the consulting firm Campaign Research, which designed 39 conservative campaigns during the last federal election (and was one of the alleged key culprits in the robocall scandal). The firm, which now employs Lee-Wudrick, also devised the successful campaign strategy for Toronto mayor Rob Ford – right down to his populist catchphrase, “stop the gravy train.” For these successes, and less than two weeks after OPIRG-Kingston lost its levy, Ciano was elected party president of the Ontario Progressive Conservatives. For their part, OPCCA endorsed Ciano’s bid, noting they were “happy to see a candidate with a comprehensive youth development plan.”

Self-Defence

PIRG volunteers tend to pay little attention to trends within political parties. Indeed, as Daifallah and Kheiriddin explain, the information age generation is largely “disengaged from the partisan political process.” This phenomenon finds practical expression in the PIRGs, which serve as a magnet for students discouraged by the culture of party politics and looking for alternatives that might undermine systemic oppression and ecological destruction.

The initial U.S. PIRG chapters emerged in parallel with the non-profit and NGO sectors. Consumer advocate and presidential candidate Ralph Nader proposed the model in 1970 to facilitate a shift from mass-movement-based activism to professional, expertise-driven interventions. Arguing that inequality had become more insidious and mass movements less promising, Nader proposed that “the new problems require more expertise, lengthy and often arduous research, and tedious interviews with minor bureaucrats.”

The U.S. PIRGs are organized as Nader envisioned, with chapters established near state capitals to enable legislative intervention. They employ “professionals – lawyers, economists, scientists, engineers” who research, advocate, and lobby. PIRGs in Canada adopted a more decentralized approach focusing on student leadership and campus life. Instead of supporting an office of professionals, they hire one or two staff to facilitate student-led research and activism.

Neither model has been spared from conservative backlash. Starting in the early 1980s, Republican politicians and conservative think-tanks launched legal challenges against the PIRGs, as did the College Republican National Committee, which distributed an “‘anti-PIRG packet’” suggesting ways “to disrupt PIRG activities and … get other campus groups to oppose PIRG.” In Canada, three PIRGs were defunded in their early years.

Anti-PIRG campaigners latch on to the most controversial PIRG activity of the era. In the 1980s, hot topics included the anti-nuclear and ecology movements. Over the last decade, Palestine solidarity activism has provoked the most sabre-rattling. These shifting targets indicate that conservatives don’t attack PIRGs because of specific initiatives. Rather, as O’Connor explained in the WikiLeaked workshop, they use controversial issues to attack the PIRG: “You’ve got to grab on to something that’s salient in the eyes of the campus community.” Conservatives don’t discriminate between PIRG chapters. They perceive the entire network as an opponent, and no PIRG position (or disavowal thereof) can convince them otherwise. “You don’t need to tell me,” explained O’Connor. “I do understand what you do. And I oppose you.”

Some PIRG supporters fear that adopting controversial positions will provoke attack. Especially after a defunding effort, PIRGs tend to endure a chilling effect during which volunteers and staff can be seduced by “neutrality” and engage in self-censorship. This was one outcome of the 2005 OPCCA attack on the Waterloo PIRG. Abiding by similar logic, other PIRGs have tried to avoid political conflict by presenting themselves as apolitical or non-partisan. Here, partisanship means more than allegiance to a political party, and refers to the basic practice of allowing your politics to inform your decisions. These reflexes are understandable, but dangerous. Recent events at the Laurier Students’ Public Interest Research Group (LSPIRG), based at Waterloo’s Wilfrid Laurier University, are a case in point.

LSPIRG secured its fee and status in 2006 and is the youngest PIRG in Ontario. However, its founders weren’t interested in joining the provincial network. Former LSPIRG member Anthony Piscitelli told Laurier’s student newspaper: “We wanted to create a place that was really non-partisan.” Nevertheless, the group became a conservative target. With some exceptions, LSPIRG volunteers and staff upheld the founders’ claim to non-partisanship, and, as a result, conservative students (including card-carrying members of the Laurier Campus Conservatives, an OPCCA member group) were able to leverage this claim to justify their increased involvement in the organization. And in the spring of 2012, conservatives won seven of the eight seats on the organization’s annually elected board of directors. “If it’s possible,” said Lee-Wudrick during the WikiLeaked workshop, “to take over the [OPIRG] board of directors … you’d be a hero to the conservative movement.”

LSPIRG’s efforts to distance itself from political confrontation made it more, not less, vulnerable. When PIRGs elsewhere have engaged in political confrontation, they’ve more consistently held their ground. At McGill University in Montreal, administrators attempted to undermine the PIRG’s funding stream by unilaterally introducing an online opt-out system. In response, QPIRG-McGill supporters have won two consecutive student referenda with “exceptionally high” voter turnout, demanding that the online system be reversed. They’ve used the attack to garner popular support, making use of decidedly un-neutral tactics, including occupying administrative offices with ally groups. Most recently, in April 2012, despite persistent suppression by the administration and a student-led anti-PIRG campaign, QPIRG won the mandatory referendum to renew its levy.

Similarly, PIRG activists at the University of Toronto (another of Canada’s oldest and more conservative schools) thwarted two consecutive defunding attacks from a right-wing Graduate Students’ Union (GSU) executive committee in 2011-12. Without understating support for its working group Students Against Israeli Apartheid (SAIA) – the most contentious issue cited in the attacks – OPIRG-Toronto ultimately won two-thirds of the votes from a GSU council that was, until then, predominantly oblivious to the PIRG’s mandate and activities. Notably, by highlighting that SAIA’s main project, Israeli Apartheid Week, has survived close scrutiny and ideological suppression since its 2004 inception, and that Israel advocates have failed to find any legal basis for their recurrent allegations of hate speech, PIRG supporters easily assumed the side of rational, compassionate deliberation.

Rebutting the charge that its work “does not reflect a consensus of the student body” and refusing to be reduced to the disgruntled activist stereotype, OPIRG-Toronto used the attacks to publicize its initiatives and, at least for now, win. Indeed, after witnessing the anti-PIRG camp in action, graduate students elected a progressive GSU executive committee in the spring.

PIRG supporters are often hesitant to strategize about conservative attacks for fear of giving their detractors ammunition. But if anti-PIRG students have access to a growing infrastructure of populist strategic support and are emboldened by their recent victories at Queen’s and Laurier, and if PIRGs are likely to lose by playing “neutral” and likely to win by fighting, it’s riskier for them to lay low.

Winning

What will the new conservative board of directors do with LSPIRG’s levy and mandate? According to Blueprint, volunteer groups are important to building a “critical mass of conservative counter-culture.” Whether it is to “take a page from the labour movement” with popular education that helps participants “question power and privilege in society … [and] be self-critical and reflective,” or to advocate “free market means to alleviate poverty” and “free market environmentalism,” Daifallah and Kheiriddin envision a youth-driven volunteer strategy to “disabuse the notion that the right is uncaring” and make it “cool to be conservative.”

Conservative youth have accordingly adjusted their self-concept. Since adopting the notion of a “conservative revolution,” they’ve experimented with language and images intended to undermine conservative stereotypes. Practically speaking, this has meant drawing on stereotypes associated with the Left. A 2008 PC ad campaign encouraged students to “freak out your profs” by telling them “you believe in bucking the establishment, thinking with your own mind, and yes – ‘questioning authority.’ In other words: Tell them you’re a Conservative.” Despite their known deceptive practices (“you will be surprised at what people will sign … if you put it in benign terms,” explained Lee-Wudrick in 2009), the anti-PIRG group at Queen’s ultimately adopted the name QSAFE: Queen’s Students for Accountability, Fairness and Equity – concepts PIRG volunteers associate with their own work.

The Right has recognized the political salience of leftist concepts, and has appropriated them successfully. These efforts coincide with the broader process by which capitalism and the state have adopted the features of the cultural Left, mainly by absorbing the watchwords of 1960s revolutionary movements and retrofitting them to serve the logic of liberal managerialism. At most universities, this process finds expression in anti-harassment policies, the existence of equity or anti-racism offices, and codes of conduct that prohibit discrimination. Of course, this managerial logic hasn’t eradicated the systemic oppression that gives rise to the now-prohibited behaviour, but it has transformed the requirements of political strategy. For conservatives on university campuses, this means orienting to and repurposing the language associated with newly ubiquitous liberal concepts.

In contrast, PIRGs and other progressive campus groups struggle to not succumb to a kind of “quality control” mentality. Faced with egregious violations of campus policy, progressive and radical students will appeal to university administrators and demand disciplinary measures, restoration of policy compliance, and, occasionally, preventative initiatives. For example, at York University, a reputed hub of radicalism, feminists struggle to respond to repeated sexual assaults on campus, falling back on demands for greater security and more efficient and vigilant administrative alerts. When someone graffitied white supremacist slurs on the office door of York University’s Black Students’ Association in 2009, student activists’ anger at university administrators for failing to condemn the racist act narrowed further to demands that they “do a better job of protecting this space.” Of course such appeals, which do have tactical value, aren’t the extent of activist strategy. However, when activists rely so frequently on the logic of demand, they become more likely to overlook its analytic restrictions and, by extension, miss opportunities to push further. The challenge of revolutionary politics is to build a base capable of not only appealing to constituted power but of displacing it. Be this as it may, quality control has its seductions, in part because it’s difficult to envision an alternative and in part because the current dynamic affords activists comfortable spaces, like the PIRGs, within which to experiment.

But relying on the university’s shallow acceptance of progressive principles becomes a liability when faced with organized conservative attacks. Constituted power will not likely defend the PIRGs, and appeals for protection from an adjudicating power can distract activists from the work of base building. Furthermore, a political strategy organized around the preservation of what some might perceive to be a subcultural scene can undermine PIRG claims to act in the public interest and therefore appear hypocritical to those who would otherwise offer their support.

Under conditions where capitalism, the state, and populist politicians have respectively appropriated the language of social movements to sell commodities, manage dissent, and win elections, the best course of action for the PIRGs is to become the political force the Right alleges them to be. Instead of repudiating the Right – whether through deflections or by appealing to “democratic” standards – this means building a base of power capable of actualizing the ideals that conservative opponents have cynically appropriated. Without emulating their populism, PIRGs can learn from conservatives’ successful emphasis on tactical deliberation, training, and infrastructure.

After all, sometimes the most radical outcomes require measures that don’t correspond with the images and attitudes associated with radical subculture. And in the context of Harper’s cross-sectoral attacks on social justice organizations – the Canadian Arab Federation, KAIROS, the National Action Committee on the Status of Women, labour unions – we can’t rely on abstract demands for fair conduct. This is politics. Politics is fighting. And if we fight, we can win.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)