Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness

By Simone Browne

Duke University Press, 2015

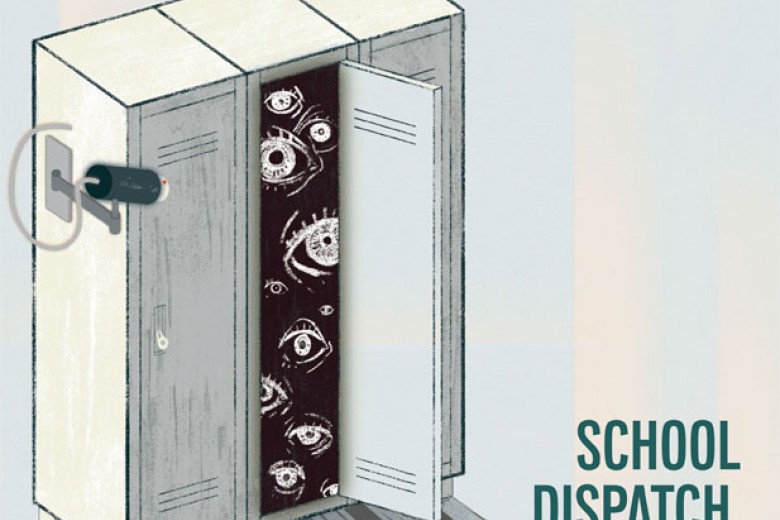

Surveillance talk is everywhere these days, but what are we referring to when we talk about surveillance? By definition, the word invokes a hierarchical position and an act: sur = over, and veillance = to watch. In practice, surveillance has multiple applications. On one hand, it can refer to methods for tracking the outbreak and spread of a particular disease in the hopes of halting it, thus saving lives. The more familiar use of the term refers to monitoring and tracking practices deployed by those possessing disproportionate power – whether states, police, middle managers, or massive corporations – practices that seem to increasingly pervade everyday life, but certainly some lives more than others. As scholars of surveillance will tell you, this unequal relationship between the watchers and the watched is, like the prison and the police, a defining feature of modern society.

Today’s global surveillance infrastructure is typically portrayed as an outgrowth of the fear provoked by 9/11 and its aftermath. Debates about mass surveillance often focus on the scale of information gathering made possible by an ever-expanding digital infrastructure. But Simone Browne’s remarkable new book, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness, offers an alternative account of modern surveillance, widening the frame by binding today’s “maximum security society” not to 21st-century fears and recent technological developments, but to the history of transatlantic slavery, capitalism, and anti-Black racism.

Browne effectively reorganizes the temporality of modern surveillance by bringing it into dialogue with the archive of transatlantic slavery, whose enduring presence lives with us long after chattel slavery’s formal defeat. Through its illuminating theorization of slavery’s afterlife, Dark Matters identifies transatlantic slavery as the antecedent to our contemporary surveillance society. Browne draws this line of connection through a careful examination of the multiplicity of modes, sites, and technologies of tracking, observation, and containment that underwrote slavery – from slave ship design and inventories to the branding of enslaved bodies, the circulation of fugitive slave notices, the visual politics of the slave auction, and the deputizing of white citizens to pursue, capture, and punish those fleeing bondage – unmasking these elements as the dreadful precursors to today’s digital databases, biometric techniques, CCTV cameras, and police stops.

Through this historical perspective, Browne traces the links between the technologies of tracking that were indispensable to making and sustaining the slave society and the violent white supremacy that animates its enduring afterlife. Here everyday practices of racial profiling – such as stop and frisk, carding, jump outs, and omnipresence, to name just a few – come into sharp focus as manifestations of what Browne calls the “cumulative gaze” of white supremacy. The concept refers to how a society’s dominant ways of looking are enveloped in slavery’s afterlife and hence reproduce “ways of seeing and conceptualizing blackness through stereotypes, abnormalization, and other means that impose limitations, particularly so in spaces that are shaped for whiteness.” This cumulative gaze is what enabled an all-white California jury to perceive, contrary to the visual evidence, a group of police officers caught on tape viciously beating Rodney King as acting in self-defence. Browne’s idea of the cumulative gaze makes sense of how white supremacy is one of surveillance society’s animating logics, long after slavery’s formal defeat and despite the formal equality that justifies mass surveillance.

Just as surveillance was at the heart of the slave system, resistance, refusal, and revolt proliferated at the same pace, freeing its subjects and haunting its architects. One of Browne’s most impressive achievements in Dark Matters is the way she weaves stories of resistance into the story of surveillance. An overbearing, oppressive surveillance society such as the one that upheld transatlantic slave society demanded tactical evasions that would facilitate escape, and Browne highlights a range of creative practices – including songs embedded with coded information to help escapees circumvent detection, the abolitionist handbills that alerted fugitives to the presence of slave patrols, the cultural reappropriations of escaped slaves’ branded bodies to signify their personal history of defiance and refusal, and stories of code-shifting and of one man mailing himself to freedom in a box.

As a study of surveillance and subversion in the long arc of slavery and its afterlife, Dark Matters also abounds with examples of present-day creative practices. Appropriately emphasizing visual representations, Browne engages the work of artists, including Robin Rhode’s Pan’s Opticon (2008) series, which provides the book’s cover art, Hank Willis Thomas’ B®anded series, and Mendi + Keith Obadike’s provocative Internet art project Blackness for Sale. A chapter that interrogates the violent scrutiny Black women are routinely subjected to at U.S. airports foregrounds the musician Solange’s appropriation of Twitter to critique and satirize the gendered racial profiling that underwrites airport security settings.

By weaving accounts of the innumerable ways in which the enslaved resisted into her history of surveillance, and by emphasizing such resistance right up to the present, Browne helps us understand not only the technological, legal, and coercive power of the overseers, but also the fragility of the power relations that surveillance is designed to uphold and reproduce.