“Oh yeah, I really feel the pressure on my chest,” Claude Laberge says. “It’s really something. It fucking sucks.”

Laberge has COVID-19. As he spoke to Briarpatch, he was holed up in a quarantine hotel with his partner, paying for it at his own expense, and expected to be moved to a government quarantine facility soon. Over the phone, he sounds sick. “Man, it’s really not a joke,” he says.

A few days before the interview, he had been released from Bordeaux, a provincially-run prison in Montreal. He was in the C Sector of the prison, and says that when he left, there were two confirmed cases of COVID 19 in the wing. Immediately after leaving, he began showing symptoms of the virus, and tested positive for it.

Throughout the month of April – as the pandemic spread rapidly through the province, making it one of the worst outbreaks in the world – Laberge says the guards didn’t take it seriously. They weren’t wearing masks, gloves, or any other personal protective equipment (PPE). They moved from cell to cell, and got close to inmates when speaking to them. Prisoners, Laberge says, were taking the pandemic more seriously than guards.

“When we had the ability to leave our cells for two or three hours a day, we were able to organize so a few of the guys from the cleaning team would be at the phones cleaning them,” Laberge says. “Same for things like the handrails. We were the ones doing it.”

“There’s this whole myth that prisons are supposed to rehabilitate people. It’s always been a myth, but it’s especially clear now. There’s no social programming, and people are being held in conditions that amount to torture.”

When an outbreak began in the prison’s E Sector, the response from prison authorities was to lock everyone down in their cells, a measure which quickly spread to other wings, like the C Sector. When prisoners were informed about the coming lockdown, Laberge says, they began to protest by shouting and overflowing toilets. The guards responded by shutting off the water to the sinks and toilets in the cells. The water was turned back on after a few days, but prisoners were prevented from leaving their cells or accessing any means of communicating with the outside world.

For Jean Louis Nguyen, whose boyfriend has been incarcerated in Bordeaux for over a year on drug charges, the situation is frustrating. In particular, he says it’s been difficult to not have contact with his partner while the virus spreads through the prison. He organizes with other family members of incarcerated people, and says the feeling is widespread.

A few days before speaking to Briarpatch, Nguyen says his boyfriend “was allowed his first call in two weeks. It was for a duration of five minutes. It was too short, but enough to know he’s managing, but finding it difficult, with no showers and being in his cell 24 hours a day.”

“The measures being taken are restrictive, but were decided in concert with the Directorate of Public Health in order to preserve your health,” reads a May 6 announcement from the prison directors to inmates, which Laberge provided to Briarpatch. “These measures are necessary to prevent the spread of the virus.”

Laberge is skeptical of how effective such measures can be, particularly for vulnerable inmates. He told Briarpatch that he was particularly concerned for an elderly man in his wing, who was being held pre-trial on drug charges.

“There’s a man in there, Mr. Langevin, he’s something like 75 years old,” Laberge says. “He’s got a hard time moving around. He has no business there. He got caught with some speed. He uses a breathing mask. I’m really scared for him, it really marked me. I hope he gets out soon, because fuck, dying in prison, it’s not right.”

That man, whose name was Robert Langevin, filed a complaint against the prison on March 27, asking for early release. After describing his many medical conditions which put him at higher risk for COVID-19, Langevin wrote “I don’t want to die here, I am an urgent case, I am a human, I have rights, I am vulnerable and I could die here, this is not human.”

A few days after Briarpatch spoke to Laberge, Robert Langevin died of COVID-19.

“They’re dealing with the health crisis through torture”

“Even after the deadlock, with every inmate in his cell and can’t come out, there was still cross contamination happening from unit to unit. And it was the guards that were doing it. They continued the practice of making guards go from one unit to the next. So they were doing a cross contamination, they weren’t observing anything, even social distancing – the guards, they didn’t practice it.”

Those are the words of a prisoner inside the Federal Training Centre (FTC), a federal prison just across the Rivière des Prairies from Bordeaux, in the suburb of Laval. A recording of the prisoner speaking about conditions inside was provided to Briarpatch on the condition that the prisoner’s identity be protected, due to fear of retribution from prison officials.

“If you ask for bleach, which we are allowed access to in here, they deny you,” the prisoner says. “They say it’s not for cleaning.”

“I’m really scared for him, it really marked me. I hope he gets out soon, because fuck, dying in prison, it’s not right.”

Souheil Benslimane has spent time in federal prisons in Quebec, but is free now. These days, he coordinates the Jail Accountability and Information Line (JAIL) hotline, and is a member of the Criminalization and Punishment Education Project.

“It was a struggle for a long time, even to ask guards to wear [PPE],” Benslimane says. “Prisoners were asking guards to wear PPE, not because they want to force the guards to do anything, but because they want to protect their own health, and the guards were refusing.”

He says that federal prisons have particular problems, including in FTC Laval. In Canada, if a person is sentenced to more than two years, they are put into federal prison, while provincial prisons are for sentences under two years. This means that federal facilities like FTC Laval have disproportionately older populations.

“A lot of people have a lot of fear, because a lot of people are old” in federal facilities, Benslimane says. “They’re comparing it to a retirement home, that’s how high the median age is. I’m hearing from younger prisoners that ‘man, I’m scared for the elders.’”

Johanne Wendy Bariteau is a paralegal and an advocate for inmates. She spent time in federal prison, including in the Joliette women’s prison about an hour outside of Montreal. She compares the situation in prisons such as Joliette to that of CHSLDs, the name given to long-term care homes in Quebec, which have been the site of the province’s most severe outbreaks.

“I would compare it with the CHSLDs,” she says, “because we’re not prepared, and have been very slow to react. It has been my experience that when it comes to inmates, we’re not very high on the priority list when things need to be changed.”

“They’re comparing it to a retirement home, that’s how high the median age is. I’m hearing from younger prisoners that ‘man, I’m scared for the elders.’”

Inside Joliette, she says, prisoners are held in house-style units which hold ten or 11 prisoners each. Prisoners in the same unit share bathrooms, kitchens, and other common areas for necessities. This means that “social distancing is impossible,” she says.

Like elsewhere in the federal system, Bariteau says that prisoners in Joliette are at a disproportionately high risk. “When I was there, there were a few women over the age of 50 or 60,” Bariteau says. “There were a lot of women living with [Hepatitis] C, a few with HIV, and they’re saying smokers are at risk and most of the people in jail are smokers.”

Like in Bordeaux, Benslimane says that the primary response to the pandemic by prison officials at FTC Laval has been to impose lockdowns and prevent inmates from leaving their cells. “If I’m locked down in my cell because of public health measures, or if I’m being punished because I hit someone, it feels like the same thing,” he says.

Bariteau also says that the way officials at Joliette have treated prisoners with COVID-19 – putting them in solitary confinement – has led women with symptoms to avoid getting tested. “Last we heard was about 50 women are infected,” she says. “But because of the way women are treated inside, a lot of women are not coming forward, because they don’t want to be put in isolation.”

Ted Rutland, an organizer with the Anti-Carceral Group, has been following the developments in Quebec prisons closely, and is angered by the widespread use of solitary confinement. “The Supreme Court has recognized solitary confinement as a form of torture,” Rutland says, referencing a recent legal victory against indefinite solitary confinement in federal prisons. “So basically, they’re dealing with the health crisis through torture.”

Demands from inside

A caravan of cars is parked outside Bordeaux on May 11, and the horns are honking. It’s a noise demonstration in support of the prisoners inside.

In the G wing of Bordeaux, Nguyen says, prisoners began a hunger strike against the harsh confinement measures in early May. According to a communique posted online by the Anti-Carceral Group, a local prison abolitionist organizing campaign, the strike and other acts of resistance then spread to other wings of the prison.

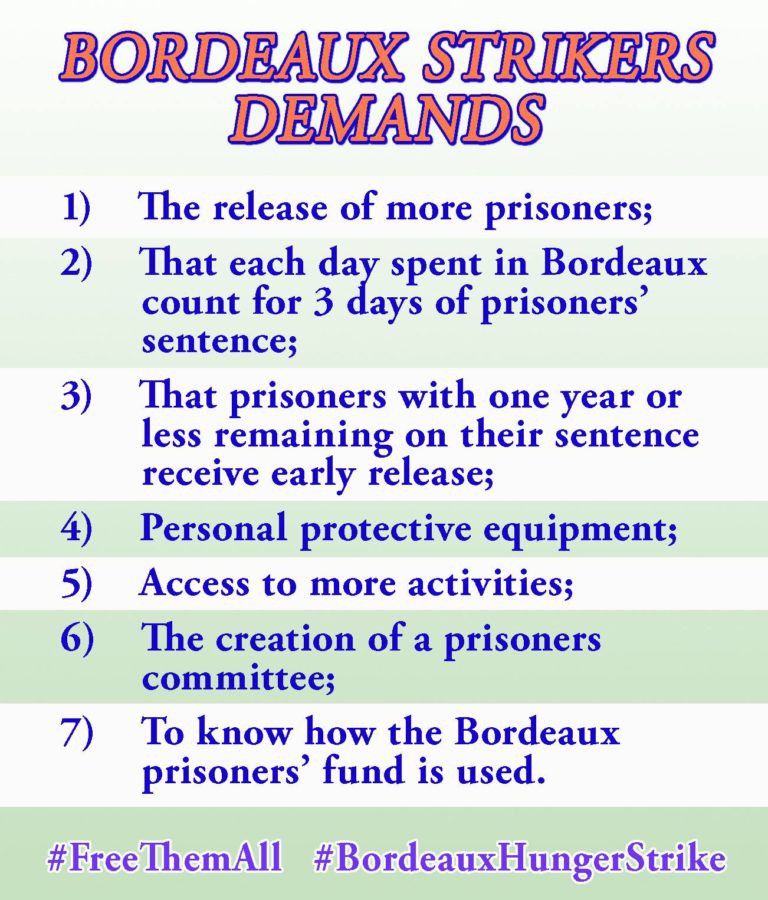

Later, the hunger strikers’ list of demands was published as well. They include wide release of vulnerable detainees; for every day spent in the prison during the outbreak to count as three days toward release; access to personal protective equipment; increased recreational activities which can be used alone in cells, such as game consoles; and the creation of a prisoner’s committee which would be recognized as the legitimate representative of prisoners by the Bordeaux administration.

Rutland, in his capacity as an organizer with the Anti-Carceral Group, has been doing his best to support incarcerated people and their families through the pandemic.

“The protests have won certain concessions from the prison,” he says. “They’re actually trying to get people inside the lockdown wings these five-minute phone calls, which wouldn’t have happened otherwise.”

But the organizing inside Bordeaux has also seen repression, Rutland says. “If people resist in any way, the prison will shut off the water system. So, they shut down the water for three days. People couldn’t flush their toilets or wash their hands.”

“It comes back to this dynamic of power and authority within the prison, and how prisoners are viewed and managed and dealt with by the system,” Benslimane says. “It’s very rough. We’re not respected, we’re not even viewed as human.

For Rutland, the pandemic is just reinforcing the critique that prison abolitionists have always held. “There’s this whole myth that prisons are supposed to rehabilitate people,” he explains. “It’s always been a myth, but it’s especially clear now. There’s no social programming, and people are being held in conditions that amount to torture.”

“We need to think about a just transition from the prison-industrial complex,” Benslimane says. “We need to re-mobilize the prison workforce, in order to make it a workforce that’s about releasing people. We don’t need this many prisoners.”

“As it stands now,” Benslimane says, “the blood of the people who have died behind bars is on the hands of Bill Blair and Justin Trudeau.”

This article was updated on May 26, 2020 to include photos of the Bordeaux prison by David-Olivier Gascon.