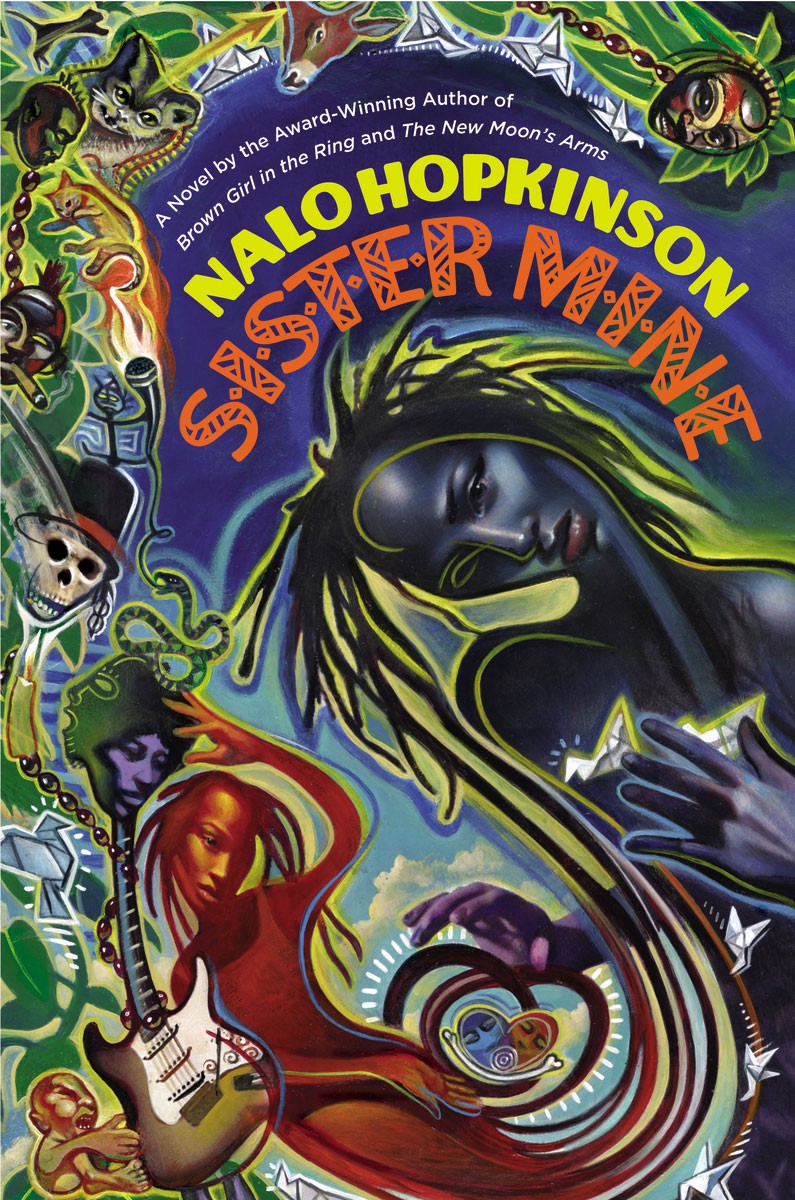

Sister Mine

By Nalo Hopkinson

Grand Central Publishing, 2013

Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way, as Leo Tolstoy said. The family of Nalo Hopkinson’s latest novel, Sister Mine, is unhappy in a way particular to a black family of sassy demigods and headstrong humans. A complexly layered urban fantasy, Sister Mine explores the space between the spiritual and material, and the murky pool where these worlds bleed together. In this meeting of the divine and earthly, family dramas take on cosmic importance. So it is with Abby and Makeda, twin sisters, born conjoined and later separated, of a “celestial” father and a “claypicken” mother, who are sent on a treacherous mission to find and save their father’s soul.

Exuding threatening mafia undertones, the “Family” are divine beings, spirits who lurk in the crevices of the visible world, shuttling souls between life and death, controlling natural forces, and imbuing certain places and people with magic, shine, or mojo. “Claypicken” is the demigod term for humans, who are considered little more than meat puppets by most celestials. Abby and Makeda’s mixed celestial-claypicken heritage is complicated by the fact Abby seems the only sibling born with special powers.

The power difference between the sisters is a source of endless bickering and deep-seated resentments, as is the sisters’ very existence for the Family, who look down on celestial-claypicken couplings. In exploring the sisters’ relationship to their heritage, Hopkinson also addresses the nature of mixed-race identity. Belonging to two different cultures often means navigating between different worlds, a metaphor that is quite literal for Makeda and Abby.

Though both sisters struggle to find their place in the spirit and material world, Makeda in particular feels lost in her mixed identity because of her lack of powers. As we might imagine of a racist white family, demigods look down on their claypicken counterparts as beings meant only to serve and then be discarded. Raised around this kind of discrimination, Makeda develops a self-deprecatory shield, calling herself a “crippled deity half-breed,” while grasping at any connections to mojo she can find within herself.

When Abby continues to dodge the question of whether Makeda has mojo of her own, Makeda gripes, “Bloody Shinies were so closemouthed about their pretty, gleaming world… Evasion, misdirection, bait and switch; whatever carrot would distract my dull donkey brain and lead my clodhopping feet away from their golden paths.” As somebody born on the wrong side of the mixed-race coupling, Makeda feels abandoned and hopelessly inferior. Her mortal status, like a racialized identity, derives not only from her lack of powers but her “donkey” body as well. Simultaneously, her connection to the celestials makes it difficult for Makeda to fit into the claypicken world. She lives in the borderlands, plagued by an ambiguity immediately relatable for anyone struggling to reconcile conflicting identities.

In creating the jagged landscape Makeda traverses, Hopkinson draws from a deep well of Caribbean, American, and European stories. Not just a coming-of-age tale, Sister Mine also reflects the tradition of twin epics, and the creatures the twins meet come from tales of the American South as well as the Greek oral tradition. This kaleidoscopic cosmic narrative overlaps with the more generic coming-of-age story, just as the magical world of the celestials is grafted onto the urban setting of Toronto. The result is an intriguing hybrid of forms that show spirituality, culture, and language as fluid aspects of modern and traditional life. At one point, Makeda answers her cellphone from the spiritual plane where celestials dwell, blurring the boundary between modern and primordial realms.

Perhaps more jarring than the iPhone in limbo, we learn Makeda and Abby are not just sisters but also past lovers. With celestials, and apparently their mixed-race offspring as well, it is common to keep it in the family. The fluidity of sexual and familial connections speaks to a queer sexuality Hopkinson explores in contrast to the heteronormative nuclear family. While the lesbian sisters and descriptions of kissing cousins are a surprise, Hopkinson doesn’t play up these relations for shock value. Though the family is certainly dysfunctional, they are not deviant. Again we find an ambiguity, between family and lover, which Hopkinson describes not as opposing but as twinned forces.

If Sister Mine is most enjoyable for its ideas, the prose does not always match their daring and complexity. There is a perhaps unintentional conflation of Makeda’s own awkwardness and the textual style. Dialogue sometimes feels like the work of contortionists stretching to make the scenario move. In the realm of the otherworldly, however, Hopkinson’s words take on an extra shine. Makeda describes the transition between realms with visceral detail: “My body turned itself inside out, my skin rubbing against itself, my organs flopping to the outside to bobble like so many lumpy calabashes hanging by their stems from the trunk of their tree.” This organic feeling pulses through the best parts of the book. Mojo may be an invisible essence, but it still relies on a messy tangle of human bodies to survive. It is in the murky meeting place of sky and earth where Hopkinson’s most imaginative writing ignites.