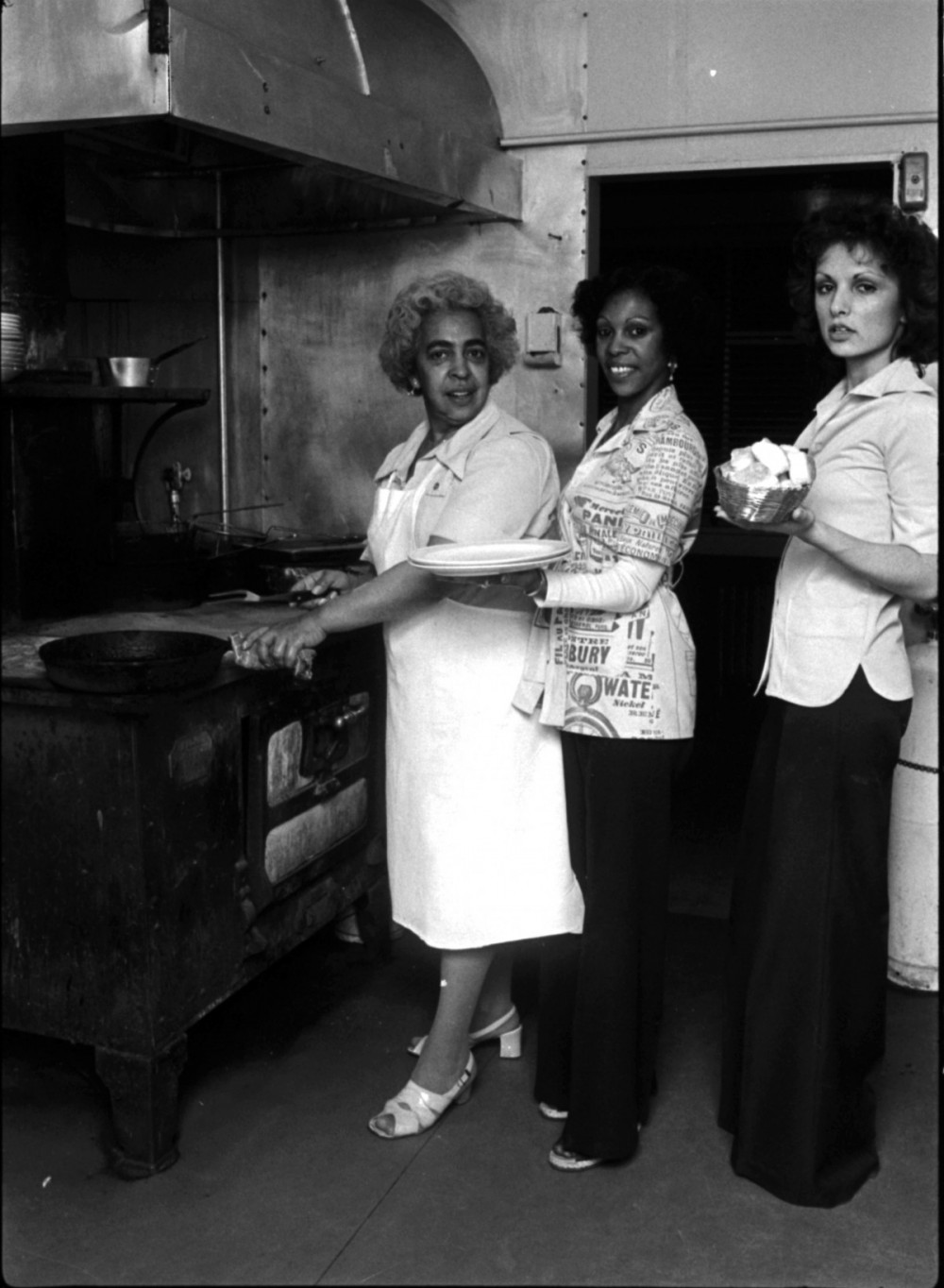

Adelene Ellen Alexander Clark (left) cooking with her daugher Vie Clark (centre) in her mother's Vie Moore's restaurant, Vie’s Chicken and Steak House in Hogan's Alley, Vancouver on November 23, 1976. Photo courtesy of Postmedia.

The summer sun was rising as LeRoy Williams finished cleaning and locked up the restaurant for the night. It was the 1960s in Edmonton, and Williams was excited to have landed a job at his great aunt Hattie Melton’s restaurant, Hatti’s Harlem Chicken Inn. Open from noon to 5 a.m., locals on their lunch breaks poured into the restaurant, found in the Senate Hotel on 98 Street, while the late-night hours brought in touring musicians and sleeping car porters after their shifts.

Williams recalls learning how to crisp fries and drop corn fritters into hot oil like doughnuts and – most importantly – watching Melton make her famous fried chicken batter. Hatti’s was one of the few places in the city where Williams and other Black workers could find a decent job, and for Edmonton’s Black community, it was a critical community hub. During Melton’s time as a restaurant owner, city officials and many white community members made “third places” – gathering spaces outside the home and workplace like churches, parks, restaurants, and community centres – hostile to Black people.

But Black communities have never been able to rely on the state for safe gathering spaces – we have always created our own. Across Western Canada, Melton and three other Black women – sisters Zena Haynes and Alva Mayes in Winnipeg and Vie Moore in Hogan’s Alley, Vancouver – were cooking up their own dishes of resistance, opening fried chicken restaurants and cementing their communities’ places in the cities.

Making Edmonton home

Melton grew up in Amber Valley, a Black settlement about 170 km north of Edmonton, founded in 1910 by Black Americans fleeing the Jim Crow laws of the U.S. South. The Canadian government had launched its “Last Best West” campaign to convince settlers from Europe and the U.S. to move to western provinces with promises of empty land and “homes for millions”; however, the government wasn’t expecting that Black settlers from Oklahoma, Alabama, and California – like Melton and her family – would cross the border too.

Across the Prairies, Black people formed settlements, including Junkins, Campsie, and Amber Valley in Alberta and Maidstone in Saskatchewan. They may have migrated north to escape the segregationist South, but Canada was not much different. In 1911, one year after Amber Valley was founded, the federal government passed an order-in-council banning Black immigration for one year. The government also paid its immigration agents to travel to the U.S. South to warn Black people about the north and attempt to keep them from crossing the border.

At this point, Canada was home to thousands of Black people – some had recently fled the U.S. and others had been born in Canada and were descendants of enslaved people. Black people’s presence across Canada was growing, and many white Canadians were determined to fight the “negro problem.” Many white people knew that third spaces were critical in Black people’s fight to make homes and establish communities in the Prairies, and similar to the segregationist institutions in the U.S. from which Black Americans had fled, white Canadians made third spaces racial battlegrounds.

There were only two gathering spaces for the Black community in Winnipeg: “Pilgrim Baptist Church, the oldest Black church in Winnipeg, and Haynes Chicken Shack.”

In 1914, the Sherman Grand Theatre in Calgary refused to let Charles Daniel, a Black man, through its doors. A few years later in 1922, the Metropolitan Theatre staff in Edmonton denied entry to and assaulted Lulu Anderson, a Black woman. Two years later in 1924, the City of Edmonton banned Black patrons from using the Borden Park swimming pool. Black women struggled to find work outside of domestic labour, and businesses hung “white help only” signs outside their restaurants – like the Gibson café, located in the historic Gibson building, just steps away from one of Hatti’s locations and where the Edmonton courthouse now sits.

While Black people were discriminated against by the city, white supremacists readily claimed public spaces. In 1931, Edmonton elected as mayor white supremacist Daniel Knott, who is known for his tight relationship with the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). To celebrate the win, the Alberta KKK lit a cross on Connors Hill.

If theatres, restaurants, and pools wouldn’t host Black people, Melton, Moore, Haynes, and Mayes would.

As Debbie Beaver, director of outreach and treasurer for the Black Settlers of Alberta and Saskatchewan Historical Society, points out, many Black people found rural life a lot safer and less racist than city life – one reason Black settlements existed several hours from Prairie cities. Despite this, Hattie Melton made her way from Amber Valley to Edmonton, and in 1944, she opened the doors to Hatti’s Harlem Chicken Inn – a gathering space and safe haven for the city’s Black community.

Melton wasn’t alone. In Vancouver and Winnipeg three Black women – Vie Moore and sisters Zena Haynes and Alva Mayes – opened Vie’s Chicken and Steak House in Hogan’s Alley, Vancouver, and Haynes Chicken Shack in Winnipeg. If theatres, restaurants, and pools wouldn’t host Black people, Melton, Moore, Haynes, and Mayes would.

Creating community hubs

Vie’s, Hattie’s, and Haynes were critical gathering spaces for Black workers, local community members, and out-of-towners. Over the phone, Moore’s grandson, Randy Clark, recalls what a night at Vie’s looked like: he paints a picture of a brightly coloured restaurant with a dozen tables and a jukebox, where workers mingled after hours and people would go on date nights. “People didn’t just come to Vie’s for a good meal, they came for a great time,” he says. Clark worked in the kitchen making biscuits, green peas, garlic mushrooms, steak, and, of course, chicken. In those days, they weren’t allowed to serve liquor, but you could bring your own bottle as long as it never made its way to the tabletop, Clark laughs.

In Winnipeg, Black sleeping car porters, who organized the first Black labour union in North America, flocked to Haynes Chicken Shack. As Andre Sheppard, a member of the Black History Manitoba Celebration Committee, notes, there were only two gathering spaces for the Black community in Winnipeg: “Pilgrim Baptist Church, the oldest Black church in Winnipeg, and Haynes Chicken Shack.” The porters’ employer wouldn’t allow them to eat in front of passengers during their long, often 18-hour shifts, so they would congregate at Haynes’ once they were off the clock.

Black communities created tight-knit communities and robust social infrastructure, and Vie’s, Hatti’s, and Haynes were at the heart of them.

In Edmonton, venues would invite Black musicians to perform but refuse to let them eat in their spaces, so musicians would go to Hatti’s after their gigs. All three restaurants became go-to spots for Black travellers and saw names like Pearl Bailey, Oscar Peterson, Billy Daniels, Harry Belafonte, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, the Supremes, Lena Horne, the 5th Dimension, Sammy Davis Jr., Sam & Dave, and Jackie Wilson.

Meanwhile, south of the border, Black-owned restaurants were key spaces for civil rights movement leaders to strategize, refuel, and connect. In Montgomery, Brenda’s Bar-Be-Que Pit was the gathering space for the most active organizers in the civil rights movement. And in Atlanta, organizers met over a plate of fried chicken at Paschal’s Restaurant to coordinate actions including the March on Washington, the Poor People’s Campaign, and Mississippi Freedom Summer.

Honouring their legacies

In the 1960s, all three restaurants were thriving hubs for their cities’ Black neighbourhoods. Black people in the Prairies and Vancouver had created tight-knit communities and robust social infrastructure, and Vie’s, Hatti’s, and Haynes were at the heart of them.

As the Black community continued to grow in Vancouver, politicians and city planners eyed Hogan’s Alley for a new viaduct. The City of Vancouver passed policies and implemented zoning tactics to make it more difficult for residents of Hogan’s Alley to obtain mortgages and permits for renovations. City officials began describing the area as heavily impacted by poverty and crime, and in a report, Leonard Marsh, a local social scientist, described Hogan’s Alley as a “slum” in need of “urban renewal.” The city approved the construction of the Georgia Viaduct straight through Hogan’s Alley, and in 1967, began expropriating and demolishing the neighbourhood.

The City of Vancouver never completed the viaduct’s construction, but it did succeed in displacing Black community members – including Clark, whose house sat across the street from Vie’s – and destroying an important cultural space. By the late 1960s, many Black community members had left the area, and a decade later, Vie’s Chicken and Steak House closed its doors. Though the City of Vancouver claims the construction of the viaduct is the sole reason for evicting Hogan’s Alley, the larger pattern of cities displacing Black neighbourhoods across North America and effectively dismantling Black gathering spaces like Vie’s suggests something more insidious. The three restaurants were the hubs for Black communities and beacons of safety where Black community members could eat, work, and gather.

Black neighbourhoods and community spaces have never been the jurisdiction of settler governments. We built our own communities and third places like Vie’s, Hatti’s, Haynes, and Hogan’s Alley are ours to reclaim.

Out of the three restaurants, Vancouver’s Vie’s Chicken and Steak House is the only one with any notable signage sharing the historical significance of the space with the community. Winnipeg’s Haynes Chicken Shack is the only one of the three restaurants that still stands, though the windows are boarded up and there is no signage indicating what once existed in the space. In Edmonton, a group of Black Albertan historians, community leaders, and Hattie’s relatives are exploring whether or not a plaque could be displayed to commemorate the important locale.

Local community groups like Black Strathcona and Hogan’s Alley Society are demanding the City of Vancouver pay reparations for the irreparable damage it caused by destroying the neighbourhood. The Black communities of Winnipeg and Edmonton – the latter being the city I call home – also deserve for our cities to recognize Haynes and Hatti’s as historical sites and provide opportunities to commemorate them. But beyond demanding recognition and reparations, Black neighbourhoods and community spaces have never been the jurisdiction of settler governments. We built our own communities and third places, and Vie’s, Hatti’s, Haynes, and Hogan’s Alley are ours to reclaim.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)