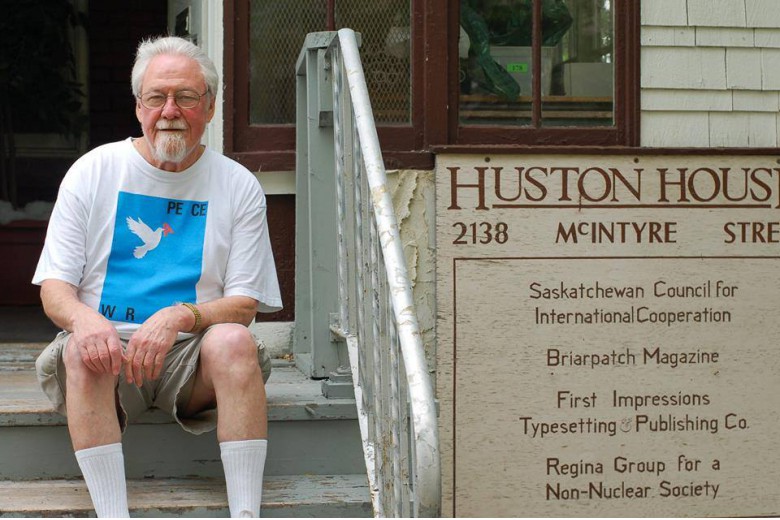

The evening that NDP MP Niki Ashton came through Regina, my hometown, I was visiting my family from Vancouver. Earlier in the day, I’d been working from home on a project for my flexible, part-time job, using my personal laptop and cell phone to communicate with my boss in Vancouver. Later, I got a short-term contract from Briarpatch to report on Ashton’s event about the millennial generation’s precarious work. All in a day’s work.

Ashton, who represents the Manitoba riding of Churchill–Keewatinook Aski, has just wrapped up a national tour to gather young peoples’ stories about precarious work. At the Regina event, Ashton and local NDP representatives gave brief introductions to the topic, and then opened the space for attendees to share how precarious work and unstable job conditions have affected their lives or those of family members or friends.

As the NDP’s critic for jobs, employment and workforce development, and as a millennial herself, Ashton is well positioned to talk about this topic. “The rise of precarious employment is driving growing inequality and threatens the future of an entire generation,” reads a statement by Ashton on the NDP website. “The government can no longer ignore the challenges facing millions of young Canadians who lack job security and basic benefits.”

In some ways, this is problem is familiar. Precarious work – including contract, temporary, and part-time jobs that don’t provide livable wages or benefits – has been increasing in Canada. A recent report from Statistics Canada found that although the share of full-time employment has grown slightly, from 62 per cent in 1974 to 66 per cent in 2014, this growth has largely left out young people: men and women aged 17 to 24 not attending school have seen their share of full-time employment drop 18 percentage points and 11 percentage points, respectively, and a substantial portion of these declines occurred between 2007 and 2014, when many millennials would have been entering the job market.

At the same time, wages have not increased sufficiently. Denise Leduc of Rankandfile.ca reports, “In the 1970s a person working full-time making minimum wage would live 10 per cent above the poverty line. Today, that same person would be living approximately 12 per cent below the poverty line.” Leduc also points out: “Whereas in the mid-1990s 1 in 40 workers made minimum wage, that figure is now around 1 in 8.”

Overall, young people today have fewer opportunities to get a good job, buy a house, and save for retirement, all while they’re facing increasing pressure from stagnant wages, crushing student debt, and expectations for greater levels of education just to earn entry-level jobs. This is not the first generation to struggle to gain skills for their chosen career, get a job, and buy a house. But young people today face a very different labour force than young people even a generation ago. Expanded free trade and integration of global markets, the rapid pace of new technologies, and neoliberalization’s tendency to deregulate and decentralize have irreversibly impacted the economy and the jobs required for that economy.

But millennials’ employment grievances aren’t garnering much response, likely because they’re not fully understood. Ashton says that the word “precarious” has only recently started to gain traction in conversations across the country. Six months ago, she told me, her team had to explain the term in policy meetings; now, the word pops up ubiquitously in the Toronto Star.

Even the term “millennial” is new to some. At one point during the event in Regina, an attendee who looked to be in his 60s began his story, “Back when I was a millennial…” His misuse of the word hinges on the fact that millennials occupy a specific context: they are people born after 1980, having come of age in the new millennium. “Millennials” is not a general synonym for “young people”; they’re young people today. Millennials grew up on Saturday morning cartoons and cassette tapes, but can now text and tweet almost in their sleep. Ours is the generation that has to #hustle because we’re working three part-time jobs, in many cases from a laptop in the neighbourhood coffee shop. Ours is the generation that is watching our parents near retirement in their 30-year careers, wondering if we will ever have such stability – or if we even want their career trajectories.

So what does Ashton want to achieve for millennials? The point of the tour was to gather stories about millennial precarity in order to determine policy solutions. As a cynic of partisan politics, I was pleased that Ashton spent the majority of the Regina tour stop listening – not getting defensive, not giving a talking point or a boxed solution to every person’s story. The space and conversation felt comfortable and welcoming (the relaxed atmosphere was likely helped by the NDP’s weak parliamentary opposition status).

If Ashton wants policy solutions, what kinds of policy options is she working with? Several solutions tend to come up in discussions about precarious work: tinker with employment insurance, raise the minimum wage, abolish unpaid internships, or make student loans less strenuous. Other touted solutions are to eliminate tuition for post-secondary education or to implement some form of guaranteed income. Others suggest tackling the high costs of housing in some markets (as a resident of Vancouver, I know all about this). Ashton told me that all of these ideas had come up at multiple stops of her tour across the country. Overall, it seems, young people are well aware of options available for addressing the problems they face.

But the most interesting thing to me about Ashton’s tour was that young people also want systemic change – and they’re articulating it. Ashton told me that she’s heard from “young workers who use the word ‘exploitation’, who talk about how their employers, governments, [and] the powerful are making profits and seeking power on their backs.”

“What I’m seeing is a lot of young people recognizing that if the status quo isn’t going to cut it, you have to challenge that status quo. You have to organize. You have to build a movement. You have to engage in solidarity. Be an ally to these movements that are challenging the status quo,” Ashton said.

On the one hand, the discussion about collective action leaves me feeling optimistic: perhaps people of all generations are interested in building movements from the ground up, establishing community connections based on real needs, and fostering grassroots organizing. But on the other hand, I’m skeptical that the NDP (or any political party) will inspire and mobilize that action.

What’s more, Ashton is short on answers as to what exactly this kind of movement would be trying to achieve. For all her talk about working together toward systemic change, she ultimately focused on specific policy changes: affordable housing, free education, reassessing trade deals. And while these changes would certainly be an improvement given the political space we’re currently in, they don’t qualify as systemic change. They’re seeking not to challenge capitalism, but to include millennials in capitalism.

With changes in technology and world markets, the nature of work is changing (though the fundamental basis of it remains the exploitation of the working class). As Jenn Prosser points out in GUTS Magazine, “Canadian labour legislation is based in an era when many men were full time wage earners and women were full time house managers,” not to mention how those racialized and oppressed by these structures were also left out of their creation. If the structures in which we sell our labour remain unchanged from the 1950s, how much can we tinker within that structure before considering a new system that better responds to people’s needs today?

To be fair, Ashton isn’t talking solutions likely because she and her team haven’t yet written their final reports on the outcomes of the tour. That’s their next step, along with a full-day forum on October 26th in Ottawa, which will feature speakers from across the country. After that, Ashton plans to introduce a federal call to action which will likely include some legislative action as well as a visionary statement on what good jobs would look like.

As Ashton told me in Regina, “There is definitely a shift happening, and it’s a powerful shift, and the question is: how are our leaders going to respond to it?” I’m wondering the same thing. And while I’m interested in knowing where Ashton takes this question, I’m not holding my breath for the NDP to be our millennial saviour. It seems we must do what we’ve always had to do: ensure a strong and connected grassroots movement for progressive anti-capitalist change, regardless of which party comes calling.