Everyone is getting into psychedelics these days. Major media outlets are publishing articles on the therapeutic benefits of psychedelic drugs. Top universities are conducting research on them, while prestigious medical journals are publishing the results as part of a growing body of scientific literature finding psychedelics to be effective in treating depression, anxiety, addiction, and post-traumatic stress. Microdosing psychedelics is a trendy way for creative professionals to boost job performance, and hardly a week goes by without a celebrity or professional athlete trumpeting the benefits of their psychedelic experience.

This research boom – coupled with grassroots campaigns – has prompted many jurisdictions to decriminalize psychedelic use. On January 1, 2023, Oregon became the first U.S. state to legalize psilocybin (“magic mushrooms”). In 2024, therapeutic psychedelic treatments will be legal in Colorado, and the use, cultivation, and sharing of psilocybin, psilocyn, N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), ibogaine, and mescaline (but not peyote) have been decriminalized. A dozen more U.S. states are expected to introduce psychedelic access laws in the next two years. Canada is lagging behind the U.S. when it comes to decriminalization and legalization, though access to psychedelics for medicinal use is slowly being expanded though Canada’s Special Access Program (SAP) and the grey market for psilocybin mushrooms has grown rapidly.

By 2027, the psychedelics industry will be worth over $10 billion, and it may eventually exceed $100 billion globally.

Psychedelics advocates are divided over how to advance today’s psychedelic renaissance. These divisions are most pronounced between, on the one hand, corporations, governments, and medical professionals who believe psychedelics should follow the route of corporate development and medical approvals, and, on the other hand, a growing number of scholars, drug researchers, and activists who argue for a more democratic model centred around decriminalization. Medicalization is at the forefront of legal access to psychedelics in the U.S. and Canada. Touted as a strategic response to criminalization, legalized medical use is typically viewed as the most viable model to destigmatize psychedelics and provide therapeutic access to patients. Biotech firms and venture capitalists also favour the medical model, which opens up the possibility of a multi-billion-dollar mass market.

But are psychiatrists, pharmaceutical companies, and the medical establishment best suited to bring psychedelics into the mainstream? While corporations and their proxies argue their approach promotes access and protection for patients, it threatens to restrict access to those who can afford to pay. The corporatization and medicalization of psychedelics is at odds with the decriminalization movement, which calls for the removal of criminal sanctions and expanded access to education, harm reduction services, and a safe supply of all drugs.

The big business of psychedelics

Psychedelics are already becoming corporatized. Large companies are clamouring to find new molecules to monetize, while smaller biotech start-ups raise capital to secure a foothold in the market. Wealthy entrepreneurs and venture capitalists are pouring billions into the sector, assigning valuations to for-profit companies based on criteria like how much intellectual property (IP) they can obtain. There are now more than 50 publicly traded psychedelic companies with shares on stock exchanges. By 2027, the psychedelics industry will be worth over $10 billion, and it may eventually exceed $100 billion globally.

These projections have companies racing to capture psychedelic IP, in the process walling off valuable information about the efficacy of certain molecules from scientists, competitors, non-profit organizations, and the public. These companies are attempting to erect legal barriers around new chemicals, as well as new formulations and applications of existing chemicals, in an effort to secure exclusivity. Psychedelic companies and researchers have applied for hundreds of patents for substances such as psilocybin, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and DMT, and dozens of these applications have been granted. Many of these IP claims involve “low-quality” patents where companies claim ownership over natural substances that in some cases have been in the public domain for thousands of years.

For example, COMPASS Pathways, a U.K.-based psychedelics company, obtained a U.S. patent on its COMP360 proprietary molecule, a synthesized formulation of psilocybin. The company plans to use the patent to assert control over a huge range of medical applications involving the substance. COMPASS Pathways employs a scorched-earth policy when it comes to psychedelics by filing overly broad patents to prevent competition. The company even attempted to patent elements of psychedelic therapy, such as the use of soft furnishings, rooms with “muted colours,” and patients holding hands with their therapists. Its strategy is to build a monopoly that would dominate the psilocybin supply chain from synthesis to therapy.

While corporations argue their approach promotes access and protection for patients, it threatens to restrict access to those who can afford to pay.

Additionally, restrictive IP models could lead to value-based pricing, meaning the costs of medical-grade psychedelic treatments will be similar to those of other brand-name pharmaceutical drugs. According to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, nearly half of all brand-name prescription drugs launched in 2020 and 2021 cost users $150,000 per year or more. To recoup investments, psychedelic companies will likely gouge patients in the pricing of the medicines and in clinical services. Johnson & Johnson is already hiking the price of its esketamine-based Spravato – one of the only legalized psychedelic drugs on the market for treating depression. For-profit psychedelic providers are also following Big Pharma’s “pill-mill model” in their ketamine treatment clinics. To increase patient numbers and cut costs, companies are neglecting key elements of psychedelic therapy such as preparing patients to take the drug, monitoring them for side effects, and helping patients integrate their therapeutic experiences into their everyday lives. Despite being crucial for patient success, the integration component of therapy is especially costly and therefore likely to be neglected in this or any other for-profit context.

Psychedelic companies have a financial stake in drug policy reform and legalization. However, many of these companies also want to limit legal access to anything outside the medical-pharma frame or that goes against their profit-driven agenda. For example, in 2020, J.R. Rahn, the former CEO of the psychedelic company MindMed, told Forbes magazine that “[t]his isn’t the 1960s all over again. I want nothing to do with those kinds of folks who want to decriminalize psychedelics.” In 2022, when the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration proposed criminalizing five new psychedelic compounds, the chief scientific officer of the psychedelic therapy company Field Trip agreed with criminalizing four of the compounds, with the exception of the drug they were working on. There is also evidence that some companies – such as COMPASS Pathways – are acting to oppose decriminalization initiatives in the U.S. These executives are effectively advocating for a continuation of the War on Drugs.

Stereotypical psychedelic advocates are countercultural leftists of the anti-war and environmental movements of the 1960s. Although psychedelics have never had a purely left-wing user base, today’s for-profit landscape is attracting a growing number of right-wing reactionary investors. They include billionaire surveillance capitalism magnate and vocal Trump supporter Peter Thiel, who is positioned to own a large piece of the psychedelics industry through his investments in COMPASS Pathways and other firms, as well as Christian Angermayer, founder and chairman of the psychedelic company atai Life Sciences and board member of the market-fundamentalist Hayek Institute. “First Lady of the Alt-Right” Rebekah Mercer also funds research into psychedelic treatments for veterans. The Mercer family is infamous for their support of right-wing causes, from financially backing anti-abortion and climate change denial campaigns to ownership stakes in Breitbart News. Corporate and right-wing interest in psychedelia demonstrates that the psychedelic renaissance is a terrain of political struggle, where the values of openness, interconnection, and solidarity commonly associated with the psychedelic experience could be overshadowed by greed, hierarchy, and authoritarianism.

Pitfalls of medicalization

Regulating psychedelics through the medical system could have benefits, like reliability of service, consistency of product quality, and a way for many patients to access psychedelic therapy. However, one of the primary reasons people are looking for new mental health treatments is that psychiatry, the pharmaceutical industry, and the medical establishment have failed in preventing and adequately treating mental health conditions. Commonly prescribed antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have faced backlash in recent years due to their ineffectiveness and often disturbing side effects.

Psychedelics may show great promise for treating mental health conditions. However, both the timing and overly enthusiastic framing of psychedelics as the next great “cure” suggests their medicalization may be less about helping those in need and more about capitalizing on epidemic rates of mental illness and tempering the backlash against drug makers and the medical profession.

These concerns are only amplified by how psychedelic research results are presented and disseminated. Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic & Consciousness Research believe that psychedelics are trapped in a hype bubble driven by media and corporate interests. In an article in JAMA Psychiatry, the researchers point out that “a disturbingly large number of articles have touted psychedelics as a cure or miracle drug.” It is true that media outlets do little vetting and often republish unfounded claims by psychedelic companies. Yet psychedelic scientists and researchers – who are sometimes in the position of conducting objective research while simultaneously advocating for the legitimacy of the field – are also subject to this criticism. Methodological limitations, such as small sample sizes, high attrition rates, and issues with blinding and expectancy bias in randomized controlled trials pervade psychedelic science. Hyped results rooted in weak methodologies have health researchers Wayne Hall and Keith Humphreys wondering “why editors of prestigious journals and scientists who research psychedelics chose to ignite a media frenzy.” Hall and Humphreys add that “psychedelic drugs have come to recent prominence through the unwise lowering of research standards by some major medical journals and the inappropriate exaggeration of research results in the popular media by scientists.”

The timing of psychedelics as the next great “cure” suggests their medicalization may be less about helping those in need and more about capitalizing on epidemic rates of mental illness.

Most psychedelics have strong pharmacological safety profiles compared to other legal and illegal drugs. Evidence of the relative safety of psychedelics is important for destigmatizing these substances and securing legal approvals. At the same time, both corporate communications and scientific publications do not adequately attend to patient safety and care. There are risks associated with the power of these drugs and the vulnerability of patients during psychedelic-assisted therapy. One review found that adverse events in psychedelic trials are poorly defined, not systematically assessed, and likely underreported. Practitioners wield a lot of power during these interactions, and there are multiple documented incidents of therapists abusing their power and assaulting patients. The hype over psychedelics as revolutionary medicines and the push to rapidly advance the field has created unrealistic expectations in potential patients and led to inadequate regulation of harms.

Millions of people have consumed psychedelics for therapeutic and other purposes for centuries, with only a tiny fraction having done so under the supervision of a psychiatrist or clinician. Nevertheless, regulators in Alberta have made it mandatory for a psychiatrist to be part of every clinic’s team. Officials claim this is a matter of safety, but those offering psychedelic treatments suggest the requirements will limit access.

“[L]ess than five per cent of psychiatrists here are willing to be involved in this therapy,” David Harder, the co-founder of ATMA Journey Centre, Alberta’s first full-service psychedelic therapy clinic, tells the Calgary Herald. Harder says that Oregon’s legalized therapy model, which requires trained, non-psychiatrist facilitators to obtain licences to conduct this therapy, is a better path for the province to follow. It appears likely that most experienced underground therapists will be shut out of medicalized systems and could face the threat of prosecution if they continue to practice.

The medical legalization route risks appropriating Indigenous medicines and excluding traditional practitioners. This mirrors cannabis legalization and the exclusion of Black people from the market, their criminalization for possession and sale of cannabis, as well as the lack of cannabis amnesty.

Confining psychedelic use to a Western medicalized framework is also problematic for those who view psychedelics as more than simply a conduit to personal healing. Framing psychedelics as solutions to individual problems feeds into self-improvement logic. It directs attention away from how medicalized therapy might perpetuate a neoliberal ideology that locates “disorder” within an individual’s mental state rather than addressing systemic causes such as poverty, inequality, precarious labour, and social exclusion (basic health care, living wages, and affordable housing would benefit depressed people more than any drug trip). And it feeds into the prohibitionist narrative that these substances are unsuitable for use outside of the medical paradigm while failing to recognize the successful community use of plant medicines in many Indigenous cultures.

Also absent in recent discourse is acknowledgement that the clinical promise of psychedelics owes much of its success to the long history of Indigenous healing practices as well as underground therapists and guides. The medical legalization route risks appropriating Indigenous medicines and excluding traditional practitioners. This mirrors cannabis legalization and the exclusion of Black people from the market, their criminalization for possession and sale of cannabis, as well as the lack of cannabis amnesty.

In addition, few people of colour are included as participants in psychedelic studies and clinical trials. One review of 18 studies in multiple countries found that a large majority of research participants were white, while only 2.5 per cent were African-American. These findings suggest both a lack of effective recruitment strategies and a level of distrust among racialized communities. As Jae Sevelius, professor of medicine at the University of California, explains: “communities of color have long histories of being abused, manipulated, and treated unethically within the context of medical research.” She adds that these communities “have been devastated by the War on Drugs and subsequent mass incarceration, and thus have much more at stake when asked by researchers to participate in studies that involve illegal substances.” The lack of diverse representation and expertise informing psychedelic research has hampered the development of culturally informed treatments and limited the generalizability of findings.

Decriminalization and alternative psychedelic futures

There are many critical voices in the psychedelic community advocating for psychedelic justice. Psymposia is a non-profit research and media organization focusing on the politics and pitfalls in “corporadelic” culture, which they argue is manifesting corporate structures and logic within the psychedelic landscape and commodifying the psychedelic experience. The group also draws attention to issues of fraud and abuse in psychedelic science/therapy while serving as an advocate for decriminalization. In 2022, Psymposia members were banned from attending a large psychedelics conference in Miami by conference organizers, suggesting little tolerance within mainstream psychedelia for views that fall outside the dominant corporate-medical paradigm. Patent “watchdog” organizations such as Porta Sophia and Freedom to Operate are also launching legal challenges against monopolistic patents in the psychedelic sector, while Decriminalize Nature is advocating for the decriminalized use of naturally occurring psychedelics for non-clinical purposes in cities across North America.

Many Indigenous communities continue to use and advocate for access to psychedelics outside of the Western medicalized framework. For decades, Indigenous groups have fought for legal access to peyote. Other groups, like the Ayahuasca Defense Fund, are fighting for access to ayahuasca and other psychedelics on human rights, cultural, and religious grounds, with an explicit focus on Indigenous knowledge and ecosystems. The Chacruna Institute is a non-profit organization that raises awareness about Indigenous plant medicines and uses, as well as issues of equity, diversity, and cultural appropriation in the psychedelic space.

Police in Canada have shut down several storefronts for grey-market psychedelics, just like cannabis storefronts were targeted in the 2000s.

Some organizations are also pursuing alternatives to the corporate for-profit model. The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, a non-profit research and educational organization, plans to produce its medicines through a public benefit corporation, which means a greater share of the organization’s revenues can be reinvested back into research and educational initiatives. The Usona Institute, a non-profit medical organization, is committed to open science and pledges to make its scientific discoveries and processes public. In direct contrast to COMPASS Pathways, it has put its process for synthesizing psilocybin into the public domain, making it available to other researchers interested in testing it. The 2023 Colorado law requires licensed entities to meet environmental, social, and governance criteria such as paying a living wage, addressing equity, and sliding scale payments. These initiatives provide potential bases for activists to advocate for open, safe, public access to psychedelics.

While it is important to think about what would be lost if the psychedelic renaissance continues toward corporatization and medicalization, there is also much to gain from the decriminalization of psychedelics and other drugs. Legal access to psilocybin in Canada is limited to end-of-life care or treatment-resistant or life-threatening conditions via Canada’s SAP. Access to the SAP is so limited that eight Canadians launched a Charter challenge to expand it, with the support of Therapsil, a group that advocates for compassionate access to psilocybin therapy.

Supporters of psychedelic legalization must situate their advocacy in the struggle for decriminalization, harm reduction, and safe supply.

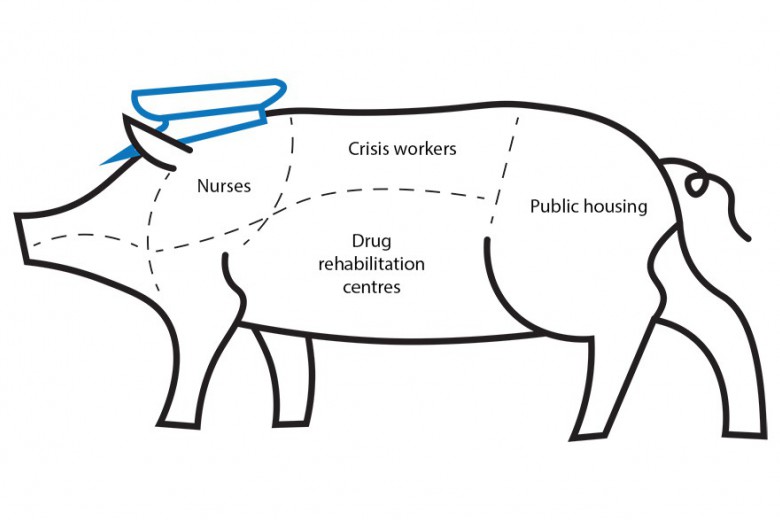

Police in Canada have shut down several storefronts for grey-market psychedelics, just like cannabis storefronts were targeted in the 2000s. Policing of drugs does not benefit anyone, except perhaps criminal justice workers. As psychologist and neuroscientist Carl Hart reminds us, the War on Drugs is mainly a jobs program and tainted drugs are killing people every day. This is one reason why the decriminalization movement fights for not only drug decriminalization, but also for the safe supply of all drugs. Because medical legalization of psychedelics can lead to tightly controlled therapeutic access, a deepened criminalization of recreational use could result, which would only strengthen the carceral state.

Supporters of psychedelic legalization must situate their advocacy in the struggle for decriminalization, harm reduction, and safe supply. Viewing psychedelic substances as superior or deserving of special legal protection risks glorifying them while continuing to stigmatize other substances and the people who use them. It also legitimizes the classification scheme behind drug criminalization and the drug war it perpetuates. Grassroots struggles toward ending the drug war and providing safe supply, like the work of the Drug User Liberation Front and Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users, should not be overshadowed by the trendiness of psychedelics.

The future of psychedelics should not be left up to governments, Big Pharma, venture capitalists, and medical professionals. It should incorporate diverse and knowledgeable stakeholders, including Indigenous practitioners, underground therapists and researchers, policy experts, and decriminalization activists. In the words of scholar Erik Davis, “[t]he mainstreaming of psychedelics may well be a positive force in this chaotic and collapsing world, but it won’t become so by simply smiling and shaking hands with the sharks that are already circling.”

*Correction: A previous version of this article stated that the use, cultivation, and sharing of psilocybin, psilocyn, dimethyltryptamine (DMT), ibogaine, and mescaline (but not peyote) will be decriminalized in Colorado in 2024. They have already been decriminalized. This version also stated that the Multidisciplinary Association for Pyschedelic Studies (MAPS) is the pushing the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to require psychedelic therapy teams to include at least one person with a clinical doctorate. MAPS plans on asking the FDA to approve MDMA as legal treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder, but hasn't made suggestions regarding the composition of psychedelic therapy teams. This is the editor's mistake and they apologize to the writers. The technical names for MDMA and DMT, 3-4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine and N,N-dimethyltryptamine, have been added for clarity.