Katherine Spilka has spent a decade working on farms. She recently worked on one in Ontario which, 10 weeks into her contract, reneged on its commitment to pay her $15/hour and instead offered her a $600 stipend for the entire season, telling her to “take it or leave it.”

“To have someone not even think that my labour is worthy of minimum wage was crushing,” she says.

Spilka was shocked to learn that, according to Ontario legislation, it was legal for her employers to pay her below minimum wage. “It was totally legal, what they were doing,” she says. “It makes me question, why is it legal to pay farm workers under minimum wage? Why is it legal to not pay time-and-a-half for overtime work?”

“Not only am I losing my job, I’m losing the place I’m living in.”

Like many in the industry, Spilka was living in housing provided by her employer at the time. On-site accommodations for farm workers often fail to meet safety standards, expose workers to workplace-related hazards and uncontracted overtime work, and put them in vulnerable positions where their housing is tied to their employment status.

“It felt like a crisis,” she remembers. “Not only am I losing my job, I’m losing the place I’m living in.”

In the fall of 2021, the members of the National Farmers Union (NFU) – Canada’s largest progressive farmer association, representing thousands of members across the country, from conventional grain growers to small-scale organic farmers – voted in favour of a motion introduced by farm workers and their allies to create a new membership type for farm workers. Farm workers like Spilka can now inform the NFU’s priorities by introducing motions at annual general meetings, voting on the union’s direction, and getting involved in working groups.

The FWWG has already gathered a core group of [...] organisers who want living wages, improved rural infrastructure including safe and affordable housing and transport, and full citizen and labour rights for all agricultural workers.

“The farm worker community is very transient,” Spilka says, which makes it hard for workers to build lasting community and act together to fight for change.

In February 2021 the NFU’s new farm worker members formed the Farm Worker Working Group (FWWG), a small group from across the country motivated to support one another, improve working conditions, and fight for ecological, economic, and migrant justice. We – Hannah and Hannen – became members of the NFU in January 2021 through the new membership type and have been involved in the FWWG since its creation.

Though new, the FWWG has already gathered a core group of active and enthusiastic resident organizers who want living wages, improved rural infrastructure, including safe and affordable housing and transport, and full citizen and labour rights for all agricultural workers.

Worker shortage or a shortage of dignified conditions?

In 2021, the Prime Minister’s Office tasked Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) to develop the National Agricultural Labour Strategy to address the sector’s dire labour shortage.

The Canadian Agriculture Human Resource Council (CAHRC) estimated that in 2017 – the last year for which data is available – labour shortages cost the primary agriculture sector $2.9 billion in revenue. The labour shortage in agriculture is predicted to increase to 123,000 unfilled jobs across the country by 2029. As farm workers ourselves, we have experienced the impact of the labour shortage on our work. The farms we work at are understaffed, and this season’s abnormally heavy rainfall made weeds spread like wildfire, caused crops to rot in the field before we could get to them, and led to workers burning out before the season’s end.

Farm workers are one of the only groups of workers in Canada that are not protected by basic labour standards.

For all their hand-wringing about the labour shortage, government and industry – the AAFC, the provincial and territorial governments, the CAHRC, and large agribusiness corporations – are dragging their feet on addressing what farm workers know are the major deterrents to entering the sector. In 2019, the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) of Ontario reported that the agricultural sector was the most dangerous industry in the province, with higher per capita rates of injury and illness than any other industry. Fair pay, dignified working conditions, health and safety protections, safe housing, status upon arrival for migrant workers, and the right to union representation will make the sector more attractive to potential entrants.

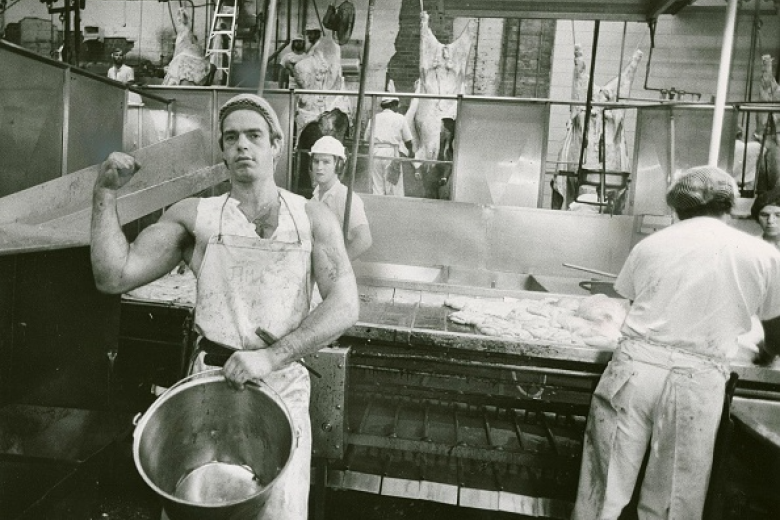

The history of farm worker rights

Farm workers are one of the only groups of workers in Canada that are not protected by basic labour standards. Depending on the province, workers are excluded from hard-won worker protections such as minimum wage, overtime pay, guaranteed rest and eating periods, and vacation time.

These conditions reflect a long trend of farm worker exceptionalism in labour legislation. Farm workers faced exclusion from the earliest laws designed to protect workers, and the Canadian government has since been slow to integrate agricultural employees into those protections.

In 1914, the Ontario government passed its first workers’ compensation acts, which made employers pay assistance to workers injured on the job. Farm workers were not included in the legislation until 1965. In Alberta, farm workers were excluded from both the 1917 Factory Act, an important piece of health and safety legislation, and the 1922 Minimum Wage Board Act, which mandated that employers pay workers no less than a certain amount, varying from industry to industry. At the time, farm owners lobbied the government, arguing that small family farms could not afford to pay their workers compensation or minimum wage.

Today, workers’ rights are still forsaken under the guise of protecting small, vulnerable family farms from the financial burden of responding to collective bargaining demands. The family farm is frequently portrayed as a “way of life” where workers must be “flexible” to respond to unpredictable weather and where rigid government labour regulation would be inappropriate. Yet farming is an industry increasingly dominated by large corporations with highly mechanized production systems, employing tens of thousands of non–family member employees nationwide. Not to mention that there is little evidence that limiting workers’ rights helps keep small family farms afloat. Legal victories won through labour organizing have been precarious, and these victories – often the result of decades of work – are swiftly dismantled when progressive politicians are replaced with conservative ones.

In Alberta, it is illegal for farm workers to form a union. In provinces like Quebec and Ontario, even when farmer workers have been granted the right to freedom of association, their right to collective bargaining has been constrained.

Formed in the early 2000s, the Farmworkers Union of Alberta, with support from the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), worked to make inroads with the Alberta Federation of Labour (AFL) and fought for improved farm worker rights. In 2015, allied with the NDP, the group helped pass Bill 6, which allowed farm workers in Alberta the right to unionize and provided them with coverage under occupational health and safety regulations, among other basic labour rights.

Bill 6 was later repealed under then-premier Jason Kenney in 2019, making unionization illegal in Alberta once again and stripping farm workers of basic protections. This decision has effectively returned the province’s agricultural workers to the 1920s.

In British Columbia, the Canadian Farmworkers Union, founded by South Asian immigrants, won farm workers coverage under health and safety legislation along with other basic labour rights under the NDP government in the 1990s. However, 10 years later, the provincial Liberal government rolled back a number of those hard-won rights, including hourly pay.

While excluding farm workers from basic protections, provincial governments have also limited the ways that farm workers can enact change. In Alberta, it is illegal for farm workers to form a union. In provinces like Quebec and Ontario, even when farmer workers have been granted the right to freedom of association, their right to collective bargaining has been constrained.

A small number of farm workers have been able to form legal unions but “those collective bargaining relationships have thus far proven unstable and often short-lived.”

In 1994, the Ontario NDP government passed the Agricultural Labour Relations Act (ALRA), which, for the first time, allowed farm workers to form unions in Ontario. It lasted only 16 months before being repealed once the Progressive Conservatives took office. The UFCW took the provincial government to court, arguing that the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms included within it the right to freedom of association.

The union mounted a similar case 10 years later in Quebec, after Quebec’s labour relations board rejected two unionization filings put forward by the Centre d’appui pour les travailleurs agricoles migrantes (CATA), on the basis that seasonal workers on these farms were not employed year-round and therefore did not meet the labour code’s standards.

UFCW technically won both cases in Quebec and Ontario, with the court ruling that the labour codes were unconstitutional and requiring both provinces to make amendments.

“As working-class people, we can’t trust the law. […] But there are other ways that people can work together, in spite of what the law says.”

In response, the provinces undertook empty revisions that managed to meet the court’s rulings without giving farm workers any real power. Ontario introduced the Agricultural Employees Protection Act, or Bill 187, which allowed farm workers to form associations but excluded them from the right to collective bargaining. Similarly, in Quebec, the province’s Liberal government passed Bill 8, which allowed farm workers to form “professional associations” under particular circumstances but disallowed unionization, collective bargaining, and strikes.

As labour lawyer Heather Jensen writes about B.C. – though the sentiment applies nationwide – a small number of farm workers have been able to form legal unions but “those collective bargaining relationships have thus far proved unstable and often short-lived.”

Sustainable agriculture means workers’ rights

“What the law tells us is that it’s illegal to form a union in Ontario,” says Chris Ramsaroop, an organizer with Justicia for Migrant Workers, which advocates for the rights of migrant farm workers in Canada. “As working-class people, we can’t trust the law. […] But there are other ways that people can work together, in spite of what the law says.”

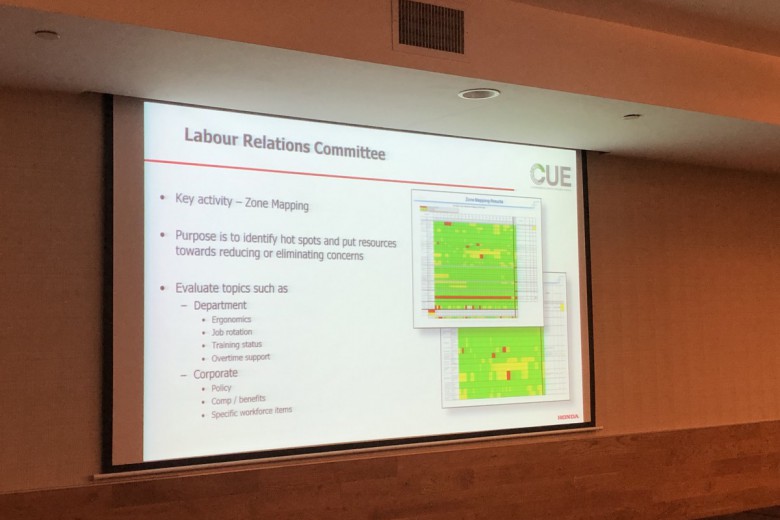

As the NFU’s FWWG clarifies its strategies and goals, it is clear that members recognize the need to organize on all fronts. This includes building coalitions between resident and migrant workers; making inroads at larger worksites; growing a grassroots base of mobilized farm workers who can share both grievances and successful tactics to improve working conditions now; and using the NFU’s existing resources and expertise in policy and research to move farm worker issues forward at different levels of government.

Farm workers have met monthly since February to determine the group’s priorities; support each other in moments of hardship; and plan base-building and popular education resources like Know Your Rights workshops and zines.

“You cannot make a living solely from farming if you’re going to keep your kneecaps by 40.”

The current membership of the FWWG is majority white, settler, and university educated. All of the active members of the working group are resident workers who work on small- to medium-scale organic farms. Our ranks do not include workers at large worksites or conventional agriculture, like big greenhouses or sites with a mixed employee workforce of both resident and migrant workers.

Madeline Marmor, a farm worker for six years, has been a member of the NFU since 2019. Alongside a group of advocates within the union, Marmor was integral to getting the new farm worker membership type approved. “You cannot make a living solely from farming if you’re going to keep your kneecaps by 40,” she says. Small-scale organic farms replace chemical pesticides and fertilizers with human labour. As a farm worker working on farms with high labour needs and low profit margins, Marmor has often felt the pressure to be fast, efficient, and not take the kind of rest she needs to be well. “My body and mental health does not fit the pace that […] our economic system sets for us,” she explains.

Marmor supported the creation of a farm worker membership as a way to improve conditions for all agricultural workers and “amp up the solidarity work” of the NFU. Like many members of the FWWG, Marmor is a first-generation farm worker whose interests in social, economic, and climate justice brought her to the industry. “Many of us have gotten into this for political reasons,” she says. “Whether it’s feeding our communities or saving the planet, or being the change you want to see in the world.”

Any plan to address the impact of climate change on agriculture must put workers' voices at its centre. And any plan to address the impact of agriculture on climate change needs broad-based, worker-led support rooted in class power.

Sustainable, ecological agriculture must mean justice for the land and justice for those working the land. Unpredictable weather means heat exhaustion and injuries for farm workers. Record-breaking droughts and flooding mean that work schedules will become less predictable, creating bad faith justification for bosses to extend working hours and for lobby groups to push against sectoral labour regulations. Any plan to address the impact of climate change on agriculture must put workers’ voices at its centre. And any plan to address the impact of agriculture on climate change needs broad-based, worker-led support rooted in class power.

For over 50 years the NFU has pushed policy and public opinion against corporate land grabs and market control, genetically modified seed, and high-input farming. It is a founding member of La Via Campesina, a global peasants’ movement fighting corporate agrarian reform in favour of democratically governed and ecologically sound food systems. As farm workers join the ranks of the NFU, it will be exciting to see how this informs a worker-centred approach to the transition to ecological agriculture.

Farm workers aren’t waiting for the law to force the farms they work on to adopt more just labour practices – they’re doing it themselves. Farm worker member Colleen Freake has worked on farms since 2010. After many months of talking to her colleagues and pressuring their employers, Freake and her co-workers recently won health benefits for full-time employees at the farm she works on in Nova Scotia. Their employer ultimately agreed with Freake and her co-workers that health benefits would incentivize skilled employees to return to the farm for multiple seasons. “It became about what the advantages are when people doing physical work have adequate health care. Those are major advantages for employers,” Freake says.

The FWWG can function as a platform for workers like Freake to share their successes and challenges in worker-led organizing.

“We are skilled workers in more than just field work and tractor mechanics. We are also labour negotiators, mediators, and problem solvers."

While the NFU currently lacks the staff capacity, translation services, and logistical know-how to responsibly support migrant farm worker membership, members of the FWWG are passionate about working in solidarity with farm workers coming to Canadian agriculture through the agricultural stream of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP), the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP), or without official status. Marmor thinks the FWWG can function as a rapid response team, engaging in direct mutual aid with migrant workers in their regions while supporting migrant-led actions against individual bosses and the labour regime that exploits them.

“What do our allies want? That’s what we can offer,” says Marmor of the FWWG. “We’re the white voice, we’re the settler voice, we’re the voice that can walk into a room when these other migrant rights organizations cannot.”

Farm workers are tough. The work requires that we be adaptable and creative in the face of precarious work and gruelling conditions. Marmor imagines a world where farm workers are able to leverage their survival skills to act in concert to improve working conditions.

“Let’s use the skills that we’ve learned, like how to remain aware and in our agency when employers take exploitative measures to keep their businesses afloat,” she says. “We are skilled workers in more than just field work and tractor mechanics. We are also labour negotiators, mediators, and problem solvers, all within the context of the Canadian farm sector. We can use these skills to help someone else.”

Using these strengths, even without legal protections, farm workers can fight against a food system that relies on unfree labour and mechanization. And we can build one that is adaptive to climate change and creates dignified employment opportunities for both resident and migrant workers.