Several months ago, after various instances of harm across the 15 chapters of a Jewish solidarity movement within which I organized – identity-based aggressions at chapter meetings, sexual assaults at events, and power hoarding by various leaders – staff members sent a call-out to movement members asking for a solution.

Wanting to keep the movement intact, and in line with transformative justice principles and the Jewish principles of tshuvah – the idea that all of us do harm and can atone for our wrongdoings to stay in community with each other – I joined a task force on harm and accountability with other care workers and anti-violence activists in the movement. We met for several weeks, reading, researching, and brainstorming together about accountability processes in leftist movements, and we developed a workshop to deliver to key movement leaders to spread this learning to their chapters.

But our work was paused when we received an email from a chapter member telling us that one of our team members sexually assaulted someone he knew, in a different movement, several years prior. The chapter member told us that our team member had been part of an accountability process to address the harm he had caused in this other movement, but that he did not adhere to the terms of the process. He implored us to remove our team member from the movement, along with every Jewish event it organized, effectively cutting him off from the leftist Jewish community he had built his life around.

The re-enactment of harm through accountability processes is something many of us have seen play out in leftist communities.

We asked our team member to step back from the task force; one of our members took on a role supporting him with accountability work, and two of us liaised with the people he had harmed. But we soon realized the accountability process we were attempting to engage in was causing more harm than good. The person who had been harmed did not want to revisit an accountability process; her friends were speaking for her, criticizing us for moving too slowly and threatening to reach out to the rest of the movement to disclose what this team member had done if we did not engage in an accountability process on their terms. We knew nothing about the process our team member had engaged in when he had initially caused harm, and we were divided over whether it was our place to revisit it. Meanwhile, movement leaders were using this one accountability process to avoid putting work and resources into longer-term processes that would reconsider staff hierarchies and restructure movement power. Ultimately, fractured in our approaches to the work and burnt out, our team disbanded, many of us leaving the movement entirely.

The re-enactment of harm through accountability processes is something many of us have seen play out in leftist communities. People who have witnessed or been involved in these processes have documented some of the tensions they produce: a survivor or person who has harmed is not willing to participate; a survivor or their friends or community members use accountability processes to exact revenge on someone who harmed them; other people involved in facilitating the processes use them to control or exert power over movements, organizations, or communities. Some have described these processes as “brutal,” resulting in seemingly never-ending cycles that fracture communities and re-enact harm – and leave so many of us wondering: how can we change these dynamics?

The TJ wheel

In the early 2000s, INCITE! Women of Color Collective Against Violence began to advocate for a new way to address harm within communities: community accountability strategies. Their work tied together what prison abolitionists and Black feminists had been saying for decades: that sexual and intimate partner violence was diminishing their ability to organize but that the anti-violence movement’s reliance on police, prisons, and courts was causing more harm to their communities. In the words of INCITE!, community accountability aimed at “preventing, intervening in, responding to, and healing from violence through strengthening relationships and communities, emphasizing mutual responsibility for addressing the conditions that allow violence to take place, and holding people accountable for violence and harm.”

Transformative justice intends to transform the conditions of violence – which means addressing and eliminating the reasons people cause harm in the first place, not just reacting to harm with punishment or restoring things to the way they were before the harm happened.

Community accountability later came to be understood as one strategy in the wider program of transformative justice (TJ), a term coined by generationFIVE, an Oakland-based collective working to end child sexual abuse, to describe “a liberatory approach to violence […which] seeks safety and accountability without relying on alienation, punishment, or State or systemic violence, including incarceration and policing.” Transformative justice intends to transform the conditions of violence – which means addressing and eliminating the reasons people cause harm in the first place, not just reacting to harm with punishment or restoring things to the way they were before the harm happened.

In the past several years, however, many leftist communities attempting to practise TJ have become fixated on – and often stuck in – community accountability processes as a way to navigate harm. These processes tend to be formalized, led by experienced mediators, facilitators, or organizers, and follow similar scripts (some organizers have actually laid out step-by-step instructions for accountability processes). Typically, they proceed as follows: a person causes harm, and the friends or community members of the person who was harmed bring that person “to the table” – either in direct communication with the person they harmed, or in contact with other members of the community – in order to acknowledge and address the harm they caused and work to repair it.

In the past several years, however, many leftist communities attempting to practise TJ have become fixated on – and often stuck in – community accountability processes as a way to navigate harm.

“Because [accountability work] has some resources around it – there are specific conversations you can have, there are concrete tasks that people can take up – it can often feel like the thing that is most empowering” when someone is hurt, says Jenna Peters-Golden. Peters-Golden was a member of Philly Stands Up, a grassroots collective active between 2005 to 2015 that worked to navigate instances of harm in West Philadelphia’s radical community.

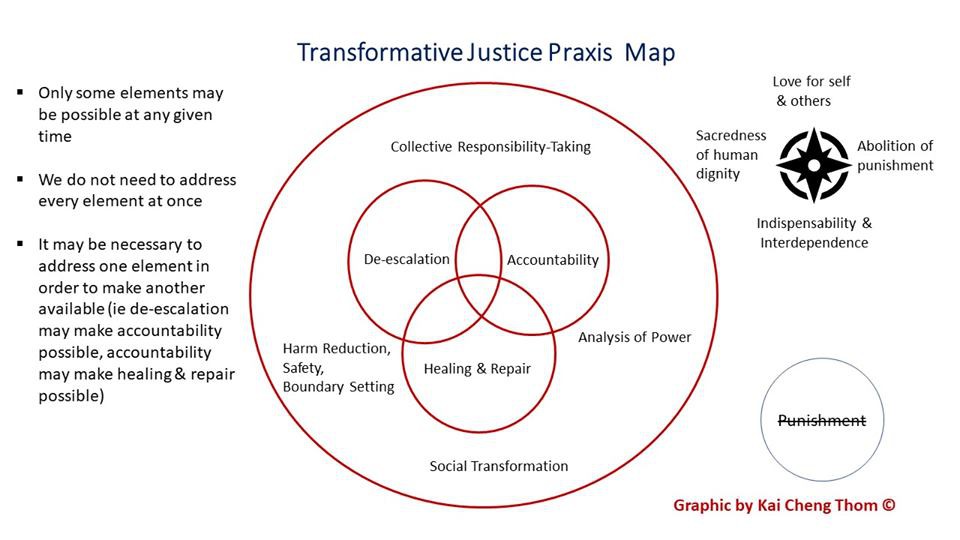

She describes TJ as a wheel made up of several spokes – including healing justice, accountability processes, abolition organizing, and community education – that are mutually reinforcing and each necessary to invest in in order to support the greater TJ wheel. Often, however, other spokes are neglected in favour of accountability processes, which can seem more concretely accessible. “There’s something really seductive about accountability as one of those spokes of TJ, [and it] can sometimes get misunderstood or misutilized for what the actual need is,” Peters-Golden says.

“Accountability in my mind has shifted so far away from engaging in actual processes,” says Dr. Rachel Zellars, one of the founders of Third Eye Collective, a Montreal TJ organization run by Black women. “I think we need to really take a step back and do baby building blocks around [TJ]."

Building blocks

“I’ve started to talk about TJ and accountability in these super-small ways, often in ways that involve radical thinking about harm reduction,” Zellars says. “As in, what does it mean just to reduce harm in this space as a form of accountability or a form of TJ?”

She tells me about a family she has been caring for over the past five years. Initially, the mother was hitting one of her children. In the first year, Zellars began hosting the two children for sleepovers to offer the single mother a break from parenting. Zellars’ goal was to prevent the children from being placed in foster care and to keep the family intact. This often entailed providing the mother with alternatives to violence in moments when she was likely to hit her child. Zellars also spoke to the family’s social worker, offering her a nearby home for short-term placements in case the children would ever be removed. Having the children placed in her home for short periods of time allowed her to work with them on their behaviour, engage them in ongoing conversations about their needs, and ultimately help them better understanding their important roles within their own home. Gradually, the physical violence between the mother and child decreased and eventually disappeared altogether.

“I think we need to really take a step back and do baby building blocks around [TJ]."

“I had to think about, in these systems and environments that are imperfect – that will continue to be imperfect – what does TJ and accountability look like?” Zellars says.

Harm reduction as part of TJ enables us to see people holistically, understanding that we cannot expect people to be present for accountability work when they are struggling to survive – and transforming the conditions that may have led to harm in the first place. In some community accountability processes, facilitators have used more formal tools to enable this kind of harm reduction. Philly Stands Up, for example, had a community network of mutual aid and emergency funds for meeting the physical and emotional needs of those involved in the accountability processes they supported. This sometimes included paying for someone’s therapy, helping them to pay rent, or supporting them in relocating.

Healing first

When she describes her own experience of asking for accountability from someone who hurt her, Kira – who asked to use a pseudonym – tells me that, in hindsight, she wishes that she had been provided with resources and time to heal from her trauma before engaging in accountability work. Kira was part of a healing justice collective for two years when one of the founders – who was also her therapist, and a person with whom she had developed a deep relationship – violated one of her boundaries. The collective, which provided health and healing services rooted in principles of social justice, had been built on the idea that wellness should be addressed not by an individual, but as a community – so Kira’s therapist sent a call-out to the group, asking for support engaging in a process to address the harm she had caused.

Within that accountability process, harm reduction entailed a list of agreements and boundaries to ensure that Kira and the person who harmed her could both remain part of their collective. These included rules about when each could use shared spaces, what could be talked about with other members of the collective, and how to navigate therapy together. But she was not presented with options for healing aside from an accountability process – and remaining in therapy with the person who had harmed her.

Accountability processes are not inherently healing. Instead, they are often draining and even retraumatizing, requiring that survivors continuously relive the hurt they experienced.

Healing is often skipped when harm happens because of the impression that accountability processes are healing in and of themselves, allowing survivors to reclaim agency and power after experiencing violence. But this can lead to anger and despair if the accountability process doesn’t go as intended – and even when all members of the community are willing to come to the table, Peters-Golden tells me that, more often than not, accountability processes are not inherently healing. Instead, they are often draining and even retraumatizing, requiring that survivors continuously relive the hurt they experienced.

“This is part of us coordinating our sectors and our movements,” Peters-Golden says, pointing back to the metaphor of the TJ wheel. “If I could say, ‘I’m going to send you to the healing justice spoke over here, where there’s all the resources you could ever need to get into generative somatic therapy; to have an affordable therapist who knows how to work with queer people, trans people, Black people, immigrants; and I’m going to find a way where you don’t have to work a 60-hour-a-week job so you can heal and take care of your body…’” they trail off, as though hoping I might intervene with suggestions for who can provide these resources. “When all of our other sectors are more robust, we can be more precise about using the tool that’s going to work for what we need.”

Scaling down accountability

When I ask Qui Alexander, another member of Philly Stands Up, to tell me about the structures that Philly Stands Up used to facilitate accountability processes, they politely push back.

“That question gets asked a lot: ‘What does it look like?’ And it’s a good question, [but] I think we, as a movement, need to challenge ourselves to ask deeper questions, because everything is contextual.”

“Accountability often looks like just refusing to run when shit gets really, really hard."

One of the deeper questions Alexander offers seems fairly simple: What does accountability mean?

“I think people are like, ‘I want an accountability process,’ but they actually don’t know what they want.” They tell me that what accountability means differs between every situation and instance of harm – “even if it’s the same person and they did similar things.”

Some survivors, Peters-Golden says, make a list of demands. This can include things like the person who caused harm providing money for the survivor’s therapy or medical needs; disseminating public or private apologies; or talking to their exes about past harmful behaviour.

Often, however, these more concrete demands for accountability end up being less important than the task of creating space for the hurt to be acknowledged and addressed. This can mean providing the space to reflect on the ways harm is handled in a community – not just after harm has been caused, but on an ongoing basis.

“I feel like we need to scale down our understanding of what accountability is,” Zellars tells me. “Accountability often looks like just refusing to run when shit gets really, really hard; then also taking time to say ‘wow, we need to talk about the missteps that we had in this process so that we don’t create this sort of disastrous bubble again.’ But, to do this, we also have to ask: how do we do better, moving through what is so often very difficult in our human relationships, so that the difficulty shifts and ultimately begins to feel like a fountain cycling its own water – that is, [it] feels less and less like difficulty and more like exactly what needs to happen?”

"How do we do better, moving through what is so often very difficult in our human relationships, so that the difficulty shifts and ultimately begins to feel like a fountain cycling its own water?"

She compares TJ work to having a regular practice, like yoga: arriving every day, moving through the same committed exercise, trusting the different circumstances of one day to the next, applying and growing our learned skills even when we feel like we’ve regressed. Preparing for TJ work on a larger scale, she says, entails starting small: modelling humility and honesty in her everyday interactions, paying close attention to those qualities in others, and preparing to apply those skills to difficult conversations when harm happens.

Aida Manduley, a New-York based social worker and TJ practitioner, agrees. “Structurally speaking, not all harm requires a big fancy structure or big groups or anything,” they tell me. “The work of accountability should be available and doable at various levels, and should be practised in the day-to-day as both community-building as well as doing work around when harm happens.”

Hurt people hurt people

This kind of scaled-down, everyday accountability requires that we turn inward, considering not only how others can be accountable to us, but reflecting on the ways in which we – as community members and even as survivors – are staying accountable to each other. In her chapter in The Revolution Starts At Home, Shannon Perez-Darby argues that in order to build our movements’ capacity to respond to violence, we must begin by “building our own internal capacity to look at and be responsible for our choices.” She calls this work “self-accountability.”

“It goes back to this myth that if you’re a survivor, you can’t also cause harm.”

“I think about self-accountability a lot as a survivor,” Kira says. She tells me that, as someone with trauma, ensuring that she does not replicate punitive or carceral tactics in her engagement with people who caused her harm requires that she constantly reflect on how she shows up in community, considering if she needs more time and space to heal before she can engage in ways that are aligned with her values around TJ. “It goes back to this myth that if you’re a survivor, you can’t also cause harm.”

What Kira is referring to is one of the principal tenets of TJ: the idea that hurt people hurt people – or, as TJ practitioners Mariame Kaba and Danielle Sered tell us: “No one enters violence for the first time having committed it.” This phrase points to the idea that people who commit harm have likely experienced violence in their own lives, asking us to trace violence to its root: capitalism, racism, ableism, heteropatriarchy. It is also a reminder that harm is cyclical; those of us with trauma who do not have a chance to heal are prone to re-enacting violence – either to regain agency, or because it’s all we’ve known.

This extends to harm that we may re-enact through accountability processes. As Manduley tells me: “When you work on issues of serial harm, sexual violence, partner abuse, and so on, especially with fellow people with trauma, you will step on each other’s shit more often than not. There is a high likelihood of greater complexity, mistrust, and volatility. It’s just how it is. That’s why it’s important to do some pre-emptive work around this, and especially have knowledge of how trauma works in the brain and what it does to the body.”

Writer and educator Kai Cheng Thom similarly explains that, because the neural networks of those of us in marginalized communities have been shaped by trauma, we are more likely to engage in survival strategies like fight-or-flight responses or black-and-white thinking when we are triggered by conflict or instances of betrayal.

“When you work on issues of serial harm, sexual violence, partner abuse, and so on, especially with fellow people with trauma, you will step on each other’s shit more often than not."

Zellars, for example, tells me about a process she was asked to join in which, after attempting to address harm with the person directly, multiple organizations sent a perpetrator of harm a letter demanding that he stay away from all of their community spaces and sponsored events indefinitely.

“Ultimately, I was like, it’s not fair for this person to be banned from so many organizations in our community,” she recalls. “What I know is that people who are excluded from everything often develop more violence and more resistance as a response. You’re kicking this person out of community without creating touchstones or anchors or a time frame or conditions for return. That is not accountability, that is punitive.”

Part of accountability work, then, also requires community members to commit to making sure that the work we engage in is aligned with the values of TJ. Organizers have created tools to support this kind of reflection; for example, the Creative Interventions Toolkit: A Practical Guide to Stop Interpersonal Violence, which provides goal-setting tools for survivors and community members to develop agreements on the nature, principles, and desired outcomes of their accountability work.

For TJ work within the collective, Philly Stands Up developed a policy of always having two people facilitate accountability processes, bringing information about the process back to the collective using codenames for those involved so that the entire group could consider if the process aligned with their values. This also allowed space for folks to process vicarious trauma and to check out of the process if needed, knowing someone else would step in. Creating boundaries around – and sometimes saying no to – accountability work that felt misaligned with TJ values became, in essence, self-accountability for the collective.

“I think the boundaries piece is huge, and I’ve lost friends and community over that, saying, ‘Actually, no, I’m not going to help you do this harmful thing.’”

Creating boundaries around the accountability work we engage in when we see that it is misaligned with the values of TJ, or coming from a place of trauma activation, requires accepting that we may burn bridges. “In doing this work, some people will hate you, block you, scream at you, ignore you – even sometimes those who asked for your help and assistance, and even those who you devoted countless hours to witnessing and loving and helping,” Manduley tells me.

“I’ve been in a position where I have to be like, I don’t think this is a good idea for anyone involved anymore – and it’s also not good for me. And if I want to actually support you, then I need to recognize when my shit’s too kicked up, or when you want an energetic punching bag.” Alexander says. “I think the boundaries piece is huge, and I’ve lost friends and community over that, saying, ‘Actually, no, I’m not going to help you do this harmful thing.’”

This kind of self-reflection is perhaps the most challenging part of accountability work: acknowledging, as individuals and as a community, that no matter how sharp our political analysis or how bold our organizing work, we too have the potential to replicate the punitive and carceral violence caused by prisons, police, and social services.

“It’s a lot of self-work,” Alexander says, “recognizing that none of us are above causing harm.”

Building transformative communities

“If you’re consenting to a TJ process, it’s ultimately so that people can share community,” Alexander tells me. “TJ is a way to keep us together, particularly when we’re talking about marginalized communities, when we’re talking about Black and brown communities, when we’re talking about queer and trans communities, when we’re talking about disabled and chronically ill folks. For us to fight the oppressor, we have to stay together. And TJ is a way for us to stay together.”

Creating boundaries and removing ourselves from accountability processes can be difficult when our goal is to stay in community with each other. “It’s important to create and work on stronger community ties to mitigate these issues,” Manduley tells me. In addition, they say, it can be helpful “to see ourselves as part of a larger tapestry; we’re not gonna change the entire culture of how harm is addressed to some nebulous perfection overnight. It’s also not any one person’s singular job. Sea change takes time, generations even. One person can’t and shouldn’t control the entire process. We have to be mindful of and accountable for our parts and keep it moving.”

"For us to fight the oppressor, we have to stay together. And TJ is a way for us to stay together.”

In 2014, the Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective (BATJC) introduced a pod-mapping tool as a way to help people engaging in accountability work to outline the small, intimate networks they might call on to support them through transforming harm. BATJC used the term “pods” because they noticed that, while most people feel connected to community in a broader sense – for example, to a religious community or to the queer community – they have few relationships deep enough to help them navigate harm, particularly if they are reconciling harm they themselves had caused.

As Mia Mingus from BATJC writes: “Once we had the shared language and concept of ‘pod,’ it allowed transformative justice to be more accessible. Gone were the fantasies of a giant, magical ‘community response,’ filled with people we only had surface relationships with; and instead we challenged ourselves and others to build solid pods of people through relationship and trust. In doing so, we are pushed to get specific about what those relationships look like and how they are built. It places relationship-building at the very center of transformative justice and community accountability work.”

“adrienne maree brown has this thing where she says, ‘Move at the speed of trust,’” Zellars reminds me. She is referring to one of brown’s principles of emergent strategy – the idea that in order for us to build strong movements, we need to reconsider the scale and scripts of our work. “Focus on critical connections more than critical mass,” brown writes. “Build the resilience by building the relationships.”

“That’s loving the people. Like, maybe I can’t stand you, but that doesn’t mean I don’t think you should be free.”

“I think this work is based on relationships. If you don’t love people, this might not be the work for you,” Alexander says. Part of relationship-building, they tell me, is about “really exploring what loving the people means.”

I ask them how loving the people is different than loving people.

“Loving the people is like loving the people that you actually don’t even like,” they respond. For Alexander, this means making sure they don’t dispose of other Black folks who may cross one of their boundaries. “That’s loving the people. Like, maybe I can’t stand you, but that doesn’t mean I don’t think you should be free.”

As they tell me this, I think about the kind of love that Kai Cheng Thom implores us to choose as the world burns around us; the kind that is “compassionate and accountable,” that “prizes each and every one of us as essential and indispensable,” that allows us to show up in community even when we are hurting, even when we have failed each other. I think about all of us who have engaged in TJ work – in formal processes and in our everyday ways of relating with each other – who continue to invest in our communities and collectives, even when it doesn’t go the way we hoped it would, even when we hurt each other; who hold on to this love – radical, revolutionary love, love for people and for the people – as the roots of TJ.