Brannavy Jeyasundaram

Kuruvikkadu is a wetland region in Sarasalai, Jaffna, covered in mangrove trees. The coastal vegetation dips its roots into the salt water, producing an ideal environment for bird species to breed over the winter. Between September and November, the skies above Kuruvikkadu are filled with constellations — a flamboyance of flamingos, chatterings of starlings, a dash of bitterns. During the height of the armed conflict in Sri Lanka, many bird species did not return to Kuruvikkadu to breed, abandoning the mangrove trees.

Much like the birds, hundreds of thousands of Tamil people were displaced from the island during the 26-year-long armed conflict in Sri Lanka. Today, Toronto is home to one of the largest Tamil diasporas in the world. Over a decade since the end of the war, some bird species have returned to Kuruvikkadu, yet they face a different threat: human-made environmental destruction. Illegal deforestation, unplanned development activities, and improper waste disposal suffocate the area. While some groups have called for the forest to be declared a protected area, local populations fear that placing the area under government control will only intensify militarization and land grabs by the army.

The form of this response is meaningful: it starts by the root with a reflection on silence, thickens into bark by calling upon ghosts, reaches upward with movement, branches into poem, and finally emerges as foliage.

This tension between preservation and encroachment is where Black Caper Films’ A Feller and The Tree begins. Set in the farmlands of Uxbridge, Ontario, A Feller and The Tree combines the faces and shadows of 28 Tamil diasporic artists with the lush imagery of natural landscapes. The film’s narrator is a tree in confrontation with its murderer, an axe. This moment, between swing and split, is extrapolated through poetic verse that evokes the experience of forced displacement and survival. The contours of the tree are not shown; some may imagine the upturned roots of a mangrove, others the silky needles of a pine.

What follows are responses to the film from five Tamil artists across generations in Toronto, one of whom participated in the film’s creation. The form of this response is meaningful: it starts by the root with a reflection on silence, thickens into bark by calling upon ghosts, reaches upward with movement, branches into poem, and finally emerges as foliage. In some sense, we make home — for the birds.

Saibruntha Arunthavashanmuganathan

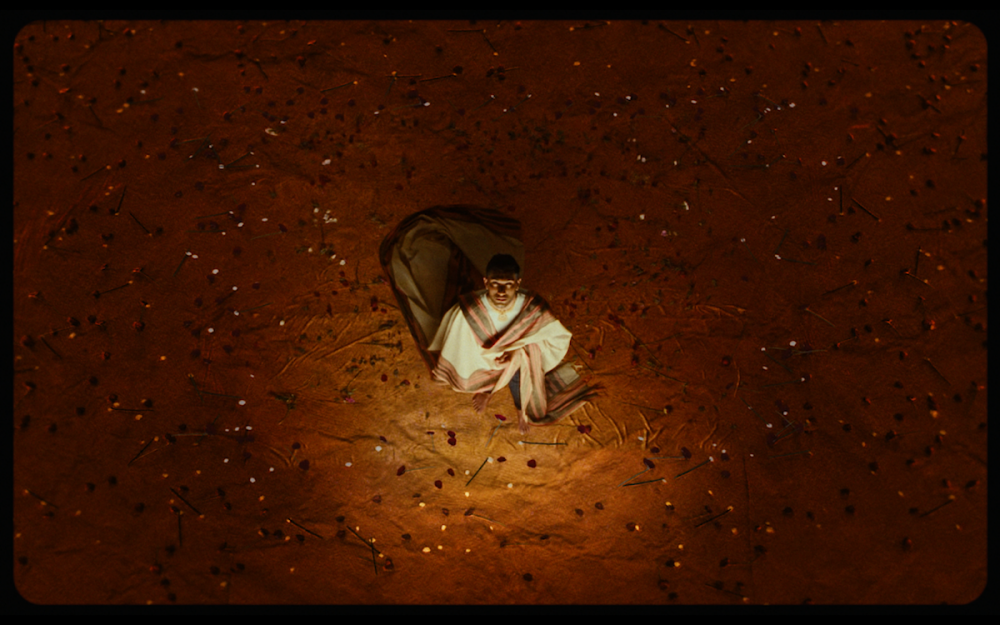

A group of us got ready early on a chilly Sunday morning, before sunrise, and headed over to shoot A Feller and The Tree. We were parked beside a field, preparing ourselves for a long, cold day. As we stepped out of our cars, fog was rising from the frosted hills, and as we kept walking, I finally saw it: the dark silhouette of a huge, lonely, broken tree, standing against the purple sky with a glimpse of sunlight streaking through the horizon. As scary as it looked from afar, when I got closer the tree felt warm, and as we stood there in our positions, symbolically as trees, we established an unspoken connection. I felt a bond with this tree and ties to the land we stood on. It reminded me of my parents leaving a war-torn land – now empty, haunted with the souls of our ancestors, just as we stood underneath this tree like ghosts with untold stories. We hear the echoes of pain and loss in not just our land, but in the land we settled on. I stood there wondering how much this tree had witnessed. If it were to speak, how many tales would it unveil of its own history? As we stood there, still and quiet, staring at this tree, enraptured by silence, it dawned on me: we are a mere reflection of this tree. Our people have travelled from one lost land to another and although we may be scarred and broken, we stand tall, strong, and resilient. Though many generations have passed, the roots of this tree and our people have withstood destruction, invasions, and erasure, but still we remain ancient, deep, and connected. As the tree said, “We are the monuments of the past and the pillars that define the future.”

Nedra Rodrigo

Tamil legends speak of Prince Vikramaditya, who brings down a corpse from a moringa tree to transport its ghost to a temple. The ghost tells stories to the prince and poses ethical questions to him, which he is compelled to answer. They repeat this process 24 times before the ghost is finally brought to the temple and released from a curse, returning him to human form. The story can be read as a metaphor for the process of mourning, as well as for working through ethical challenges a king must face in governing justly.

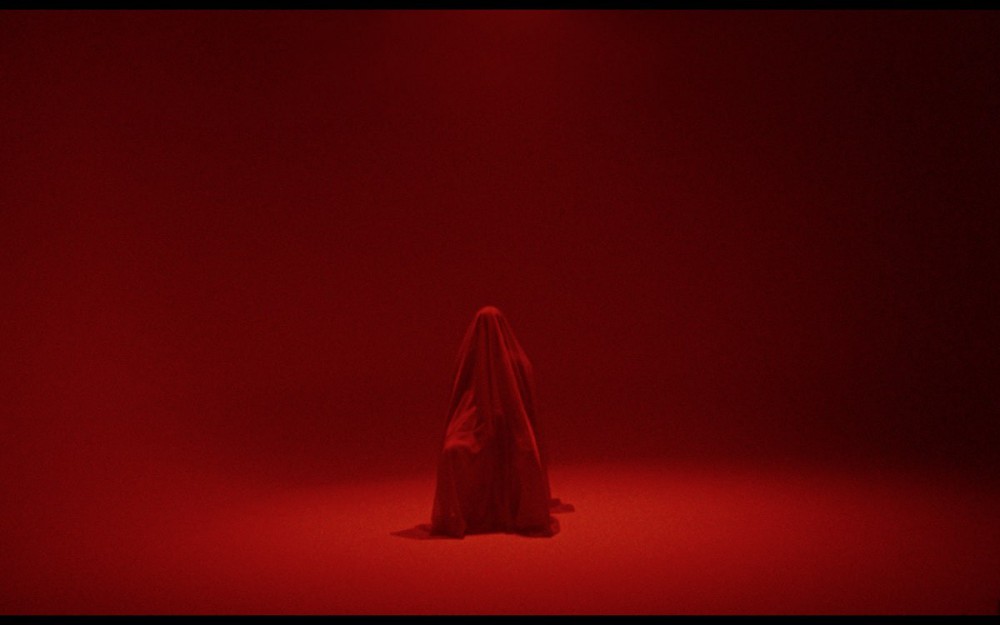

In A Feller and The Tree, the diasporic condition is suggested through the slightly dissonant voice of the tree, which turns into a forest of voices, and through the invocation of the dead that stain their roots and the ghosts that hold them upright. A diaspora of mostly refugees, haunted by its dead and dispossessed from familiar landscapes, finds itself in an ethical quandary when confronted with ongoing Indigenous genocide in its adopted land. Moving between internal and external spaces, figures wearing veils and smeared in ash intensify the fugue unfurling through voice and music.

A diaspora of mostly refugees, haunted by its dead and dispossessed from familiar landscapes, finds itself in an ethical quandary when confronted with ongoing Indigenous genocide in its adopted land.

In the film, we enter an in-between world where trees are bridges between earth and sky. The tree becomes an ethical conduit between the solidity of soil and the symbolism of language. The film flickers between light and shadow, suffused with deep shades that emerge in twilight, and it draws from the Tamil poetic mode of tinai, where the five types of landscape found in Tamil homelands are linked with specific flora, fauna, and moods. The film immerses the viewer in the landscape of the forest (kurinchi), where the mood is a longing born from separation. The images of trees that are not native to Tamil homelands underscore the psychic loss of the displaced. The subtitles hint at what cannot be transferred from one land to another: when the narrator speaks of “mango and moringa trees” in Tamil, their words are translated in English only as “trees,” losing their cultural specificity and weight in the modes of tinai.

Shanta Ponnudurai

The ultimate goal of Indian classical art is the evocation of rasa. Translating from Sanskrit to “juice” or “taste,” rasa is not merely aesthetic pleasure, but its relishment. It forms a sacred bond between aesthetic subject and spectator. The dhvani, which is the soul of poetry or a poem’s suggested meaning, serves as an undercurrent for the development of rasa.

In the classical dance tradition of bharatanatyam, there are nine distinct states of rasa; A Feller and the Tree takes us through many of them. From its first frame, a stunning network of trees, we experience both bhayānakam (fear) and kāruṇyam (compassion): fear of the reckless feller and compassion for the tall trees who withstand destruction. We then face a lone asymmetrical tree, half barren and half plentiful, which proclaims: “Feller! Listen closely.” Bhayānakam is transformed into veeram (heroism). In a flashback sequence, a beautiful woman, draped in a rich sari and adorned in temple jewellery, appears behind fabric. She wears the remnants of a thriving culture and returns us to kāruṇyam.

Translating from Sanskrit to “juice” or “taste,” rasa is not merely aesthetic pleasure, but its relishment. It forms a sacred bond between aesthetic subject and spectator.

There is a poetic line that follows: “We are the bridge between earth and sky.” I am reminded of my many students scattered across the globe. From my study of bharatanatyam in India to my return to Jaffna as a teacher, and then my relocation to Australia, then Singapore, and finally Toronto — there is a chorus of dancers that remain connected to me and to each other through this movement art form.

In the film’s final frame, six dancers bathed in darkness hold postures resembling trees while a single light flashes behind them. We hear overlapping voices say, “This is our home.” We are left with an emotion that propels us into the future: hope.

Renee Vettivelu

stars visible from isolation

as Ursa major turns to minor and the earth twirls the river’s tide a metronome

and the forest is flooded with ancient harmonies

a feller approaches my feet

an angelic dialect revealed in the fruit i bear

and still a spear through my side was not the first time they’ve crucified the heavens

my looming body becomes tangled in the scattered harvest

how foreign to decay tangent to my roots

as stump

reductive yet rudimentary

antithesis and yet akin

i am lone

though the skies have not abandoned me

it’s dim i yearn for the commune of a constellation

for another night of melodious and collective laughter

a ballroom parking lot orchestrated dance class

a celestial drumbeat our soulful awakenings

but the dagger has drawn the bridge divided and conquered

and earth returns to earth

however

borders have no effect on moonlight

nor gravity nor could the feller

the will of illumination is truth bearing freedom itself

lunar persuasion reminds every river that flows through me who to trust

and memory a reactive force compels each surrounding tree to stiffen its spine

our grief-built foundation revolution birthed skeletal resistance

this forest is our home

Shanthiya Baheerathan

When I was six, my mother, a bharatanatyam teacher in Hatton, on the island, taught me how to embody a tree. “Root yourself to the ground,” she said, “your branches must be sturdy,” while pushing down on my arms to make her point. “Resist the wind. Thread your arms toward the sky, the light, as a tree would.”

She has always referred to the natural world as sentient. There is a saying in Tamil that she often uses: “vai paisatha mirugangal.” Loosely translated, it means “animals that do not mouth-speak.” She has never questioned whether voicelessness meant a lack of a perception or a lack of consciousness. So as I sat with her to watch A Feller and The Tree, we took the tree’s voice as both metaphorical and literal.

Like the tree, we are sensing, we are grieving, we are in relation to place, we are rooted, we are here.

The tree’s voice boldly centres non-human ways of knowing and thinking, and for me, when the dancers silently embody trees in the film, they begin to disavow the politics of recognition in favour of reconnecting with something more fundamental: a way of being. Like the tree, we are sensing, we are grieving, we are in relation to place, we are rooted, we are here.

The politics of recognition often involves proving our humanity, our suffering, our sorrow. It involves making ourselves more understandable, so that we are afforded space in the world. A Feller and The Tree does not make compromises in pursuit of recognition; rather, it takes our connection and our responsibility to the land and to ourselves as a given – and it does so, carefully, by threading ourselves with the “vai paisatha mirugangal.”