The end of contract supper starts out like a normal meal in a normal restaurant, but then Smiley hails the waiter and the five of us closest to him realize it’s on. With an hour left on the open tab, the waiter is doing his best, black tie swinging as he takes drink orders on his way up the table towards us. The camp boss and the owner are down the other end and everyone’s still using indoor voices.

“Are you ready for dessert?” the waiter asks.

Smiley puts down the menu and says “I’ll have the baseball steak,” and the waiter’s eyebrows do the wave, same as at a hockey game.

I’m done a Sterling Sirloin. Hammy had a New York. Chewy is cleaning up a surf and turf. Kenny the Kindle Cutter sits back from his prime rib. Thibeau, maybe on account of the fever, ordered chicken and there’s a napkin over it. I’ve had a double Caesar and another, so I order dark beer. Hammy is on rye and gingers. Chewy’s on rum and cokes. Kenny downs Budweiser. Thibeau believes he’s fighting scurvy, so he’s nursing vodka and oranges.

“Yes sir,” says the waiter, taking the plate from in front of Smiley, “how would you like it? With all of you, I forget how you had your first one.”

The first time, Smiley froze. Because he was called sir or had never had a steak to order, I don’t know.

“Medium rare, with a baked potato.”

The waiter gives a slow and serious nod. The menu says a baseball steak is so thick, the most they can cook it is medium-rare.

Smiley proudly wears a flannel jacket that could cloak a barbeque. The way he walks in it, his shoulders back, you’d swear it was a uniform with a medal for each year of service, though all the years are in his face. Creases like the grain in dark cherry ripple as he sips iced-tea.

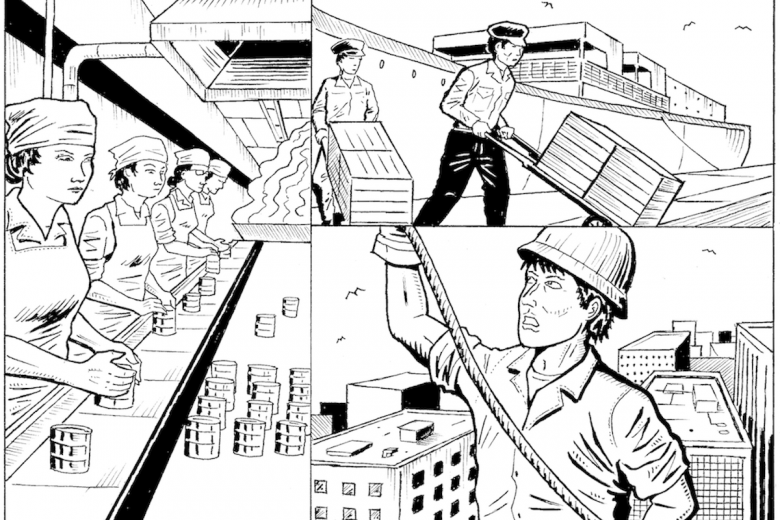

We are brush thinners. Piece workers. Groomers of the forest green. We go into land that was reforested too densely and knock down all but the best crop trees. We eliminate the competition so they grow wide into logs rather than pencil-thin and tall, striving for sunlight. After us, the trees get plump, rounder at the bottom. We’re told that overall they come back quicker and stronger than if we let nature do it on her own.

We closed the contract late in unreal snow. Snow like in children’s books. Snow haphazardly shelved in laden branches of Spruce trees so a clumsy motion brought it down swift and shocking into your collar and down the back of your neck. Before you shrugged it away, it felt like an enormous owl on your shoulders. Then, if only for a second, it muffled the always groaning saw.

The snow came early, heavy and often and made for tough access on the logging roads and even slower and more dangerous progress for us. You couldn’t run because you had to place your feet. One guy ran and beneath the white blanket his foot slid between two windfallen trunks. His body kept moving, not his foot. They are going to have to try to rebuild his ankle down South.

The cold followed the snow. It made it hard and crunchy and on one block of land we killed time while waiting for stragglers at the day’s end by building an igloo. At the start it was easy, but we didn’t take it very seriously and didn’t have any idea how it would go at the end. For the last half hour of the last day in that area we were wide eyed kids, even the camp boss, trying to finish our igloo before the last guy wandered to the van. We barely did before we had to leave. The last few blocks were carved in a rush, inexpertly, while we supported the others. Once the circular cap piece was slipped into place atop the structure, each block was reliant on the ones it touched, making it whole.

The cold takes a toll. It’s been twenty or more below for three weeks and it numbed us and ground us down and made us sick and it cut deep into our dwindling crew that used to be fifty strong. With the holidays looming, men are sneaking away to the airport or by night time bus, whereabouts unknown.

Those of us left are opportunists, or lifers. Thibeau and I are opportunists. The contract was pie. We got as big a piece as we could. Hammy, Kenny, Chewy and Smiley are lifers. All they eat is pie. Next season there would be more. Working into December meant more work, more money, more meals cooked for them. It wasn’t the worst life, but they are lifers. By December, they are sick of pie.

Smiley’s steak arrives. Earlier in the season, I’d seen him leave the dinner tent after polishing off two plates of supper. He sat on an overturned milk crate with his belly like a beach ball between his knees.

“You should try the dessert sandwich,” he said, mischievously. In his hand was a piece of apple pie between two pork chops.

When the waiter comes back, it’s nearly time to close the tab and we want drinks. Smiley leans back and opens the menu.

“A dessert for you tonight?” asks the waiter, recognizing he still has it in him.

Smiley takes his time, on purpose. Only you wouldn’t know it unless you knew those lines around his eyes. For the waiter’s benefit, he studies the menu.

“I’ll have the baseball steak,” he says, exactly like he’s ordering his first.

The waiter’s eyebrows climb his face like a kitten in a tree that doesn’t know how to climb down. Hammy and Kenny are mirthful and Chewy who knows him best cackles like it’s an old joke he knows but loves to hear. He bangs on the table with his hand. This isn’t noticed, as along its length, we’re getting going pretty good and long gone are indoor voices. The restaurant has stopped seating people in our section and the manager hovers nearby.

Kenny had told me privately that the two previous years only a select few – those without a drinking problem – had been invited to the end of contract meal. The rest had a bonus added to their last cheque. The meal was supposed to be secret. Someone told someone though and soon everyone knew. Kenny thought the distinction between who could come and who couldn’t was flimsier than a Walmart work boot.

Some of the closest to Smiley went to him. That was Chewy, being a cousin, and a few of the others who were quiet and didn’t speak a lot of English and used their own languages. For a few seasons Smiley had been a go-between for them and management, clarifying hours and start dates and layoff papers, trusted by all. He helped navigate the shared camp world between the rules and details of the day-to-day and the men who came from the far north to work the contract.

Before leaving town to head out for the last shift, which was to be a work-as-many-days-as-it-takes grind, the owner spoke to us in the small lobby of the hotel. He thanked us for our hard work that season and for sticking it out. When he finished, Smiley asked him straight up, in front of us all, if everyone could come to supper. Smiley said it takes everyone to close the contract and it wasn’t fair to only invite some. The owner looked at the group of us dedicated enough to still be there and no head was still. That’s how Smiley and his boys got to attend their first end of contract dinner.

Smiley was a gambler on the best streak of his life. It wasn’t compulsive and he seldom bet money. He was doing it as calmly and confidently as he wore his work boots and jeans into the restaurant that night. He had been betting all season and had kept rolling his winnings forward. He’d bet on the right contract – it went longer than any rival contract had and it made him good money. He’d bet on how to talk to our sweet, dark-eyed cook, Isabelle – who made our mouths water and who saved Smiley the drumstick from the turkey, the seasoned first slice of the roast beef, the biggest muffin each morning. He’d even bet on the right bed – it cradled his suspect back so it didn’t give him too much trouble. He’d bet on how the owner would react to his request to open up the end of contract dinner to everyone and he’d quietly bet the five of us, so you couldn’t tell if he was joking or not, that he could eat a baseball steak for each year he’d worked for the company.

“The back pay will be delicious,” he boasted.

When the waiter comes back, his brow is wet. It is past 9 PM and he’s been working for it. The tab is supposed to be closed. The waiter takes Smiley’s plate.

Smiley sighs and opens the menu. It’s balanced on his belly and there’s a whiff of the impossible at the table with us amongst our empties. Then one of them down the other end takes notice. He’s a veteran and has been there for a few of the suppers. He sees the menu, the tilt of the waiter’s head, sees us stone-still, watching.

“Tab ended at nine, boys,” he says loudly, so the owner and the waiter hear him, “anything here on in is on you.”

For the first time in hours, there is quiet along the table. We sit with our last drinks, ice settling in the rocks glasses, free beers half empty, feeling like we had our hands slapped.

“C’mon, Smiley,” says Hammy with wonder, then, with a whisper – “grand slam.”

“I’ll have the baseball steak,” says Smiley, and snaps the menu closed.The table erupts into hoorays, peals of laughter and one wild yee-haw, all of it underscored by Hammy’s squealing and Chewy banging his fist on the table over and over.

“And I’ll buy you that steak,” yells the camp boss and the joyous sound redoubles. The last table in our section picks up and hastily leaves. The manager is showing them the palms of his hands.

On two occasions that season some from our camp spent a cold night in the holding cells in Ignace, once for hoisting garbage barrels like the Stanley Cup, hooting victory and hurling them concussively against the brick wall in the parking lot of the IGA. That season one of us lost a week’s wages on an upturned card and an unexpected flush. That season we jumped on borrowed picnic tables until they collapsed like Chilkoot pack horses, then made a bonfire from the carcasses. We toasted the night sky and made deliberately slow marches through the flames, work boot soles softening, secret guts of embers exposed and searing red below a darkness shot through with wavering emerald columns.

We’d had shouting matches, fist fights. Tables had been tossed aside like shovelfuls of snow. We failed to call home, forgot, neglected, or couldn’t pay credit cards. We rode in taxis and rented hotels and bought beer and shots for sudden friends. We’d backed a work van into a fire hydrant. We’d missed work, missed rides to town, missed rides back to camp. We’d been too hung over on day off in town to do laundry and had to wear reeking, sweat crusted clothes for another six-day shift. We’d missed out on conversations and plenty of women, well, there really are none to meet up here, but we really had no chance the way we got.

The waiter comes back, hair limp, shirt coming un-tucked and there’s Smiley with that menu open to the desserts. The waiter says nothing, only stands there shaking his head side to side. Smiley orders the Belgian Chocolate cake. He takes a last look at the menu and the price he must realize would buy a whole cake at a grocery store.

“Sir,” says the waiter, a few minutes later, reaching with a spotted sleeve across the table and setting down the plate with its chocolate bounty, “with my compliments.” For a second, Smiley looks at him, uncertain.“No charge, sir,” says the waiter and our friend’s face widens and crinkles.

The cake is out of a magazine. It’s huge, it doesn’t look real. Smiley picks up a dainty fork in his giant mitt and pushes it down into the point of his cake. He lifts it and closes his lips over it, pinching and pulling the silver clean. His cheeks move as he tastes it.

“How’s that?” I ask, breaking the spell. He comes back from a long way off, looks up and over at me, swallows.

“That’s the best cake I ever tasted in my life,” he says and there go his eyebrows up the tree.

Coming in we were bundled against the cold. Leaving, it’s another story. Some are stumbling, some singing. Faces seem sunburnt, no one’s cold. The manager insists he arrange taxis, rushing off to make it happen. Kenny bets Hammy fifty dollars he can’t put fifteen napkins down his pants. Thibeau bear-hugs the slack-armed waiter, who is past defending himself.

In the parking lot outside, our jackets are unbuttoned, slung over shoulders, or on snow banks. We’re laughing, we’re unstoppable. Smiley stands steady, plenty warm in his Sudbury dinner jacket, belly full of steak and iced tea and asks what we’re going to do next. Thibeau has six cigarettes in his mouth, lights them, passes them out. Hammy pulls a napkin out of his pants, then bends double, chugging out plumes of breath like a steam engine.

The first taxi turns into the parking lot. I shake Smiley’s and Chewy’s hands and then the hands of Smiley’s crew, wishing them all the best. The group is headed different places and some are all done for the night and season and in an instant we will start to dissolve again into our own lives.

For months we rode quietly shoulder to shoulder in the work van. Then the snow came and those of us who hung in until we brought the contract down realized something. In December, with the earth in its furthest orbit from the sun, rays coming in slow and low over the North like migrating geese touching down on a black lake, when the nights are the coldest, the longest, we find ourselves in the tightest orbits with each other and that is well worth celebrating.