“Remain constantly alert for opportunities to send our informants to Canada and give consideration to such action in all instances where warranted. Information developed in the racial field which is of interest to Canadian authorities must be furnished to the Bureau promptly.”

These are the closing lines of a secret memo, written in November 1970 by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, alerting the Bureau to the “black power situation in Canada.” The memo is just one example of how the FBI and RCMP were attempting to build connections between the international Black Power movement and groups they labelled as “of extreme concern” in Canada during the late 1960s and 1970s. These included Caribbean nationals residing in Montreal and Toronto, the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ), Black Panther Party supporters, and Black nationalists.

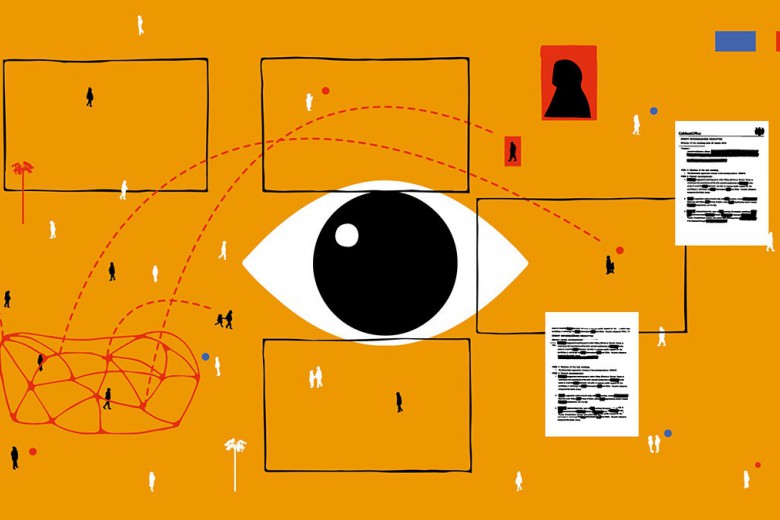

The Hoover memo, filed under the heading “Black Nationalist Movement – Canada,” is among thousands of internal documents of the FBI’s counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO). COINTELPRO aimed to – in its own words – “disrupt, misdirect, discredit or otherwise neutralize” leftist and progressive movements in the United States from 1956 to 1971. This included targeting civil rights, Black Power, Puerto Rican independence, anti-war, and student organizations – sabotaging, infiltrating, arresting, and even assassinating their members. The file resides today, along with most other COINTELPRO volumes, as a part of the FBI historical archives at the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

But as COINTELPRO records become more accessible in the U.S., accessing equivalent records in Canada remains extremely difficult.

In April of 2021, member of Congress and veteran Black Panther Party member Bobby Rush proposed the COINTELPRO Full Disclosure Act, a congressional bill that requires U.S. government agencies to release all records related to the counterintelligence program. The legislation would allow for public use of historical COINTELPRO archives to understand the full extent of the FBI’s warfare against its own people.

But as COINTELPRO records become more accessible in the U.S., accessing equivalent records in Canada remains extremely difficult. Despite the RCMP collaborating with the FBI and undertaking similar acts of surveillance, infiltration, sabotage, and racial terror, Canadian historical archives that detail the RCMP’s role in COINTELPRO are heavily classified and censored. As a result, accountability from the Canadian government for these abuses is entirely absent from policy discourse.

Researching Canadian state security south of the border, however, presents an entirely different scenario. In 2006, the U.S. government implemented an automatic declassification system – meaning that any records that concern relations between the United States and a foreign government (like Canada) qualify for declassification after 25 years, with few exceptions. Rather than relying on Canadian government sources for records that remain overly censored, researchers can look to records held by NARA for historical details of Canadian state security from a U.S. perspective. This includes the RCMP’s role in the warfare of COINTELPRO.

Canadian COINTELPRO

By the late 1960s, the FBI and RCMP had coordinated their surveillance of members of the Black Power movement who were crossing the border from the United States into Canada. In a secret report to Ottawa headquarters in December 1968, director-general of RCMP security and intelligence William Higgitt reported that “U.S. Black Panther members have been actively engaged in attempts to gain control of civil-rights leadership in the Halifax and area Negro community.” Higgitt’s report is a part of a 2,000-page file titled “General Conditions And Subversive Activities Amongst Negros, Nova Scotia.” A heavily redacted version was released to the Canadian Press in 1994 by CSIS (the Canadian Security Intelligence Service) under the Access to Information Act. Three quarters of the pages were withheld in full.

Stokely Carmichael delivering a speech before the Congress of Black Writers in October 1968. Photo courtesy of McGill University Archives.

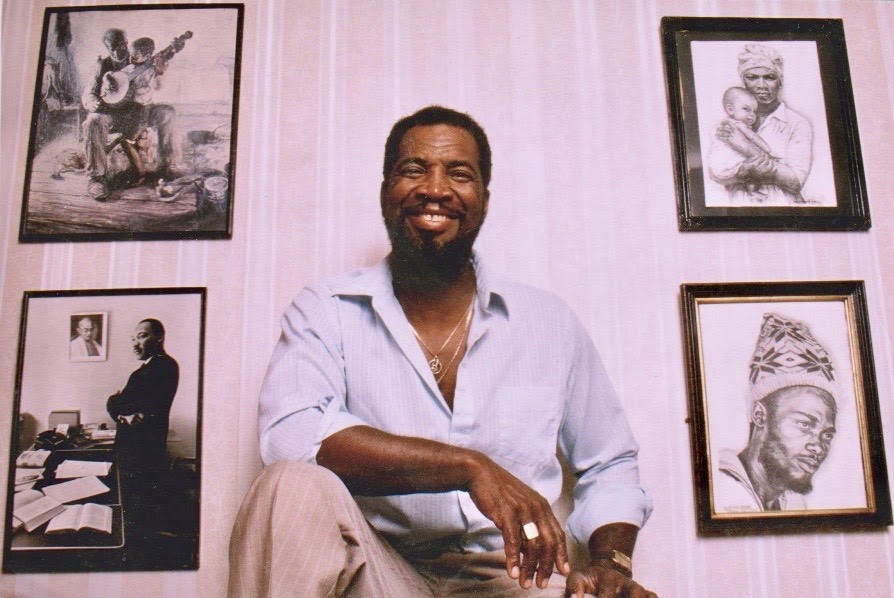

Higgitt was likely citing a visit to Halifax by the “honourary prime minister” of the Black Panther Party, Stokely Carmichael, in October 1968. Carmichael’s arrival followed his attendance at the Congress of Black Writers in Montreal, where he delivered a speech and built connections with prominent Black organizers such as Burnley “Rocky” Jones and Rosie Douglas, based in Halifax and Montreal, respectively. A second visit to Halifax followed weeks later, by two other Panthers, T.D. Pawley and George Sams.

What Jones and Douglas didn’t know at the time was that Sams was an FBI agent. He began his career in 1967 by infiltrating the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, where he became Carmichael’s bodyguard. He would work as an informant for the FBI for more than 10 years, often encouraging acts of violence by Black organizers to justify their surveillance, arrest, or assassination. On Sams’s visit to Halifax, both Douglas and Jones would be arrested by the police: Douglas for loitering and Jones for a revolver that mysteriously appeared in Jones’s car while Sams was driving it.

One can only wonder if Sams’s presence, the revolver, and the subsequent arrests were among the early instances of what Hoover alluded to in his 1970 memo: the FBI supplying the RCMP with Black informants to surveil and suppress the “black power situation in Canada.”

When I contacted James Walker, a longtime comrade to Jones and the co-author of his autobiography, he was surprised to learn for the first time through our exchange that Sams was an agent provocateur for the FBI. “This really is a bombshell,” said Walker, who witnessed Jones’s and Douglas’s arrests.

Walker recalls sitting in Jones’s basement in 1994, the two men reading Jones’s RCMP file together. The names of informers, and likely Sams’s name, had been redacted among the pages of vile racist slurs used by the RCMP. One page included a report from the day Jones picked up Carmichael and Miriam Makeba from the Halifax airport in October 1968. The RCMP even noted how Jones switched cars with Walker for the airport trip, knowing he was constantly being watched by the police. “I thought he was being paranoid,” Walker tells me.

One can only wonder if Sams’s presence, the revolver, and the subsequent arrests were among the early instances of what Hoover alluded to in his 1970 memo: the FBI supplying the RCMP with Black informants to surveil and suppress the “black power situation in Canada.” On his return to the U.S., Sams would go on to aid numerous FBI raids of Panther Party offices after being implicated in the torture and murder of Alex Rackley of the New Haven chapter in May 1969.

Burnley “Rocky” Jones. Photo courtesy of Kwacha House.

Today, the documented history of George Sams as an agent provocateur is public, thanks to the combination of declassified FBI documents, courtroom testimony, radical journalism, scholarly research, the teachings of elders, and published literature and film. But in the archives of Canadian state institutions, the telling of Sams’s visit to Halifax, the 2,000-page RCMP file on Halifax’s Black community, and the broader coordinated RCMP-FBI campaign of racial terror against the international Black Power movement continues to be a closed and redacted history under the Access to Information Act.

Since its inception in 1983, Canada’s Access to Information Act has had a nearly identical mandate to the Freedom of Information Act in the United States: “to enhance the accountability and transparency of federal institutions in order to promote an open and democratic society.” Why then, in practice, are there such vast differences in the outcomes that these acts produce for their citizens, especially in accessing historic security state records?

Legislating secrecy. Obscuring history.

COINTELPRO remained a secret until March 1971, when the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI raided boxes of files from an FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, and released them to the press. Over the past five decades, many volumes of COINTELPRO files have been made public through the U.S. federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) of 1966. In the wake of the Watergate scandal and the exposure of government lies about the Vietnam War, the FOIA was broadened in 1974 to include access to federal files of law enforcement, intelligence, and security agencies that had formerly been severely restricted.

Today, online libraries such as the National Security Archive, the FBI Vault, the CIA Reading Room, and the declassified FBI archives at NARA provide public access to thousands of volumes of COINTELPRO memorandums – an outcome of decades of FOIA requests, lawsuits, and declassification. FOIA researchers still struggle with slow processing times, zealously applied exemptions, and legal challenges – but overall, FOIA has fostered the broad study of U.S. national security.

By comparison, the process of accessing the archives of Canada’s security state is layered with greater secrecy, years of delays, and ultimately more censored results. “Something unique is slowly strangling Canadian history, and we should call it out,” wrote Paul Marsden, a former military archivist for Library and Archives Canada (LAC) and NATO.

The culprit? Canada’s Access to Information Act.

Prior to 1983, Canada had a broad declassification system that regularly made the records of federal agencies available in national archives after they turned 30 years old. Declassification was governed by a cabinet directive, making it a mandatory procedure across government and a function of administrative discretion under the Oath of Office and Secrecy and by the Official Secrets Act. Once the Access to Information Act (ATIA) came into effect, agencies began cutting their retention periods and offloading their records to national archives over shorter time frames without first declassifying them.

According to a senior LAC archivist, over 80 per cent of archives stored in LAC’s “top secret” vaults are not actually top secret.

For LAC, formerly National Archives Canada, this meant the number of records they received annually for processing and storage increased exponentially, tripling in the first year alone. Even today, LAC faces immense backlogs, both in receiving and processing archives from federal agencies and in fulfilling requests for access to records under the ATIA.

Although the ATIA legislated a framework for Canadians’ “right to request” information, it also expanded government powers to censor that information by creating categories that are exempted from disclosure, such as the conduct of international affairs, national security, and law enforcement. The ATIA assumes this information to be “injurious” to the government with no consideration to declassification or the passage of time. A century-old classified file is given the same “security risk” consideration as a classified file created yesterday.

The Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada (OIC) has found that requesting classified historic records under the ATIA – especially if the records are stored at LAC – commonly results in unwarranted censorship and withholding. Much of this is because national security archives are excessively classified by CSIS.

According to a senior LAC archivist, over 80 per cent of archives stored in LAC’s “top secret” vaults are not actually top secret. The only way to declassify or downgrade the security status of files is by getting approval from CSIS. Both OIC and LAC officials agree, given the scope of historical and specialized knowledge required to declassify or downgrade these files, CSIS’s capacity is limited.

FOIA researchers still struggle with slow processing times, zealously applied exemptions, and legal challenges – but overall, FOIA has fostered the broad study of U.S. national security.

CSIS opposes this view. When I asked a CSIS official what justifies CSIS’s continued classification and oversight over historic state security records stored at LAC, they responded, “The material is sent to CSIS for review because it has the expertise to determine what information still requires exemption. LAC does not have access to the resources we do to make informed decisions.”

An image of a redacted newspaper article about the Sir George Williams Affair from the RG146 vault. Photo courtesy of the author.

But when one visits the LAC building on Wellington Street in Ottawa to view declassified records, it becomes clear that CSIS’s interpretation of what qualifies as an ATIA exemption is beyond the scope of the Act. In the sparse collection of previously released ATIA requests for RCMP Security Service records, for example, the files are so excessively censored that even clippings from major Canadian newspapers are completely redacted.

The result of these contradictions and federal infighting over who is qualified to declassify historic national security records has been years of delays and over-censorship at the expense of meaningful disclosure and a knowledgeable public. In practice, this means that the story of FBI and RCMP collaboration remains perpetually classified and is less accessible in Canada than in the United States, with the border serving as a smokescreen.

The RG146 vault

Today, the archives of the RCMP Security Service and CSIS are held in Record Group 146 at LAC. The archive is a collection of original source documents and microfiche, telling the story of the government’s secret policing of thousands of labour, student, immigrant, Indigenous, and anti-racist groups since the end of the First World War.

Notable volumes listed in the finding aid include the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, the 1930s Communist Party of Canada, the 1940s Anti Fascist Mobilization Committee for Aid to the Soviet Union, the Black United Front in Nova Scotia, and the 1969 Sir George Williams University uprising. Although we can see thousands of volume titles, their contents remain classified and withheld under exemptions of the ATIA.

Since 1989, LAC has received transfers of these archives from CSIS, which inherited the RCMP Security Service files. Despite many RG146 records being well over 40 years old, the files remain under CSIS control and continue to be closed to the public. The only way to try and access a file is to submit an Access to Information request. The file must then be sent back to CSIS and every other relevant federal department to determine what they wish to censor – a process that routinely extends the ATIA response time by years and makes timely research impossible.

This means that when a previously released RG146 record is cited in literature from the 1990s or 2000s, if LAC archivists can’t locate the ATIA copy, it’s as though the request to release this information never happened and the process of access must start all over again.

Author and scholar Steve Hewitt was among the first researchers to file ATIA requests to RG146 files during the 1990s. In his book, published in 2000, Spying 101: The RCMP’s Secret Activities at Canadian Universities (1917–1997), Hewitt noted how available literature on the history of the Canadian security state lags far behind similar work in the United States. As a doctoral student in the 1990s, Hewitt was hopeful that public use of the Access to Information Act would allow research on Canadian national security, state warfare, and political repression to catch up.

His hope was short-lived.

“[S]ignificantly less security material, even from documents that are over forty years old, is being released now than when I began as a researcher,” he wrote in 2012. “This suggests the potential for future historical writing about Canada’s security state to grind to a halt due to a lack of primary source material as those with a vested interest in the present prevent an interrogation of the past.”

Adding to the problem of censorship is the absence of a central online repository of national security and intelligence records, especially those that have been previously released under the ATIA. Canada’s “Open Government” portal includes only a fraction of ATIA summaries that have been processed by federal agencies over the two most recent years – and that’s if agencies upload any data at all. Every month, the portal erases ATIA summaries that exceed the most recent two-year window.

“This suggests the potential for future historical writing about Canada’s security state to grind to a halt due to a lack of primary source material as those with a vested interest in the present prevent an interrogation of the past.”

The “Open Government” initiative also excludes the ATIA requests that were processed and released between ATIA’s inception in 1983 and the portal’s creation in 2011, including requested and released records from RG146. When I asked LAC and CSIS why previously released state archives under the ATIA are not preserved for public use, they indicated that the majority of previous requests have been lost or destroyed as they are not considered of “historical value.”

This means that when a previously released RG146 record is cited in literature from the 1990s or 2000s, if LAC archivists can’t locate the ATIA copy, it’s as though the request to release this information never happened and the process of access must start all over again. In effect, the ATIA system erases itself through administrative sabotage.

The Key Sectors program

The RG146 files that Hewitt did access and wrote about in the 1990s illustrate how the RCMP Security Service attempted to understand new social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, which diverged from the “Red Scare” communist threats of previous decades.

The result was a Canadian equivalent to COINTELPRO called the Key Sectors program, which began in 1967 under the RCMP’s counter-subversion division and gathered information on the New Left, Black and Red Power, second-wave feminism, Quebec separatism, and anti-war movements, among others. The program operated on the premise that radical groups could threaten the government by targeting three main “vital sectors” of society: the government, the media, and educational institutions. It also involved a parallel campaign to recruit civilian informants, and gave the RCMP discretion to counter or contain threats using the same “disrupt, misdirect, discredit or otherwise neutralize” tactics as COINTELPRO.

While many of the RCMP Security Service’s dirty tricks – such as forged letters, break-ins, informer infiltration, and planted bombs – are more commonly known from their campaign against the FLQ, the full extent of their activities remains unknown. To avoid exposure, the RCMP destroyed many of their operational files following the Citizens’ Commission exposure of COINTELPRO in 1971. Exposure would arise, however, much more incidentally.

The program operated on the premise that radical groups could threaten the government by targeting three main “vital sectors” of society: the government, the media, and educational institutions.

It was in July 1974 that a bomb would accidentally detonate at a private residence in Montreal, injuring Robert Samson of the RCMP anti-terrorist unit. Months later, he testified that there were “much worse things” than bombings and break-ins that he had done as a member of the Security Service. The incident launched the federal McDonald Commission to investigate RCMP abuses, which eventually recommended removing security and intelligence responsibilities from the RCMP. In 1984, the government acted on the commission’s recommendations by creating a new national intelligence agency: the Canadian Security and Intelligence Service, or CSIS.

In the United States, COINTELPRO exposure by the Citizens’ Commission resulted in the public hearings of the 1975 Church Committee, which investigated illegal intelligence operations of the CIA, NSA, and FBI. In Canada, the McDonald Commission mirrored this undertaking – but each federal investigation has had a markedly different legacy.

In the U.S., the combination of FOIA databases, repositories for previously released information, long-standing federal declassification initiatives, and direct access to the courts have allowed requesters to continue opening and publishing COINTELPRO files.

One example that demonstrates the importance of these efforts is Shaka King’s 2021 Oscar-winning film Judas and the Black Messiah. The film follows Fred Hampton, chairperson of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party, as the FBI infiltrates the chapter and eventually assassinates Hampton. It shows COINTELPRO at work, as well as how the FBI falsely framed the Black Panther Party’s revolutionary movement as a terror threat to white people.

In one scene, white FBI agent Roy Mitchell has a conversation with William O’Neal, a Black informant, detailing why O’Neal has been asked to infiltrate the Party and gather intelligence on Hampton. “The Panthers and the Klan are one and the same. Their aim is to sow hatred and inspire terror,” says Mitchell.

This film scene – one that illustrates how the FBI manufactured the image of the Black Panther Party as a racial terror organization equivalent to the Ku Klux Klan – may never have been written had it not been for over 50 years of grassroots organizing, the teachings of veteran Panther leaders, lawsuits brought against the police and the FBI, and appeals to the FOIA system to liberate COINTELPRO files.

Daniel Kaluuya and LaKeith Stanfield in Judas and the Black Messiah (2021)

In the past year alone, newly released FOIA documents have revealed the direct involvement of Hoover and senior FBI officials in the plot to assassinate Hampton, and in its cover-up. Had this information been revealed earlier – during the 13-year civil lawsuit that began in 1970 against the government actors involved in Hampton’s killing – this information would have greatly influenced charges against the state.

In April, public momentum from the international reach of King’s film translated into legislative action and the proposal of the COINTELPRO Full Disclosure Act before Congress.

By contrast, the McDonald Commission has not produced similar impacts on security state research and public policy in Canada. The creation of CSIS one year after the implementation of the ATIA has meant that access to RG146 records has always been obscured by the censorship powers of the Act. Meanwhile, the federal government has stymied historical research of its state institutions: the immeasurable hours that went into processing thousands of RG146 release packages, much like nearly all of the packages themselves, destroyed in the name of “no historic value”; the drastic failures of the “Open Government” portal and lack of a searchable public database that includes the data of released records and the records themselves; and the Harper government’s killing of the “Coordination of Access to Information Requests System” database, which disclosed ATIA request summaries across government agencies dating back to the early 1990s.

What the Canadian state considers “open government” is not so open at all, and for RG146, access to information has meant a cycle of censor, erase, and repeat.

Countering Canada’s administrative sabotage

Over a year ago, I asked a senior archivist at LAC for the previously released file on Burnley “Rocky” Jones from 1994. I was informed that the release package for this file is “long gone.” Forced to repeat work the Canadian Press did decades ago, I filed an ATIA request for the file in February 2021, knowing that it would be sent to CSIS to censor the file all over again. After an ATIA request is filed, the requester is to be notified by the institution about when they can expect the requested records. A year later, I have yet to receive even that notification, let alone the file itself.

The ATIA is currently undergoing its 14th major review by the Treasury Board in four decades, a process that has repeatedly proven itself to be irrelevant to legislators and has failed to create meaningful systemic change. If the system continues to perpetually censor or block access to state archives for another 40 years, what is at stake?

The history of repressive tactics used by the Canadian and U.S. governments – separately and in collaboration – can help us understand how these counterinsurgency programs have reinvented themselves today. RCMP violence against land defenders in Wet’suwet’en territory and at Fairy Creek; the use of private security forces at Standing Rock; the cases of Hassan Diab, Mohamed Harkat, and other Muslims criminalized as terrorists under secret security certificates; the torture of prisoners during the war in Afghanistan; and the FBI targeting of the Movement for Black Lives as terrorists under the label “Black Identity Extremists” are but a few examples of these reinventions.

The lack of disclosure under the ATIA is not just a matter of history – it is a crucial driver of public policy that causes premature death for those impacted by police, military, and other institutional state violence within Canada’s borders and abroad.

On deaths due to police violence in Canada, for example, policing institutions and police unions do not collect and publicly disseminate detailed information about use of force incidents, and there is no public entity that tracks this information. Access to any RCMP information at all through the ATIA is in such a state of crisis that in 2020, the OIC tabled a special report to Parliament to address the RCMP’s systemic lack of compliance with the Act.

On military matters, Canada’s transparency and reporting on the war in Afghanistan is in a similar situation. In 2019, following a three-year FOIA lawsuit, the Washington Post published hundreds of interviews with senior U.S. government officials who publicly lied about making progress in the war. Meanwhile, hundreds of equivalent interviews conducted by the Privy Council Office with Canadian officials remain undisclosed.

The lack of disclosure under the ATIA is not just a matter of history – it is a crucial driver of public policy that causes premature death for those impacted by police, military, and other institutional state violence within Canada’s borders and abroad.

From examining the state of the ATIA and efforts to access Canada’s archives, we begin to understand that the preservation of Canada’s security state – its policing, military, intelligence, and penal institutions – all relies on the censorship of its archives. What the ATIA deems to be “injurious” to the government, is in reality a measure of liability for injury and premature death to those impacted by state violence.

Perhaps this is why the McDonald Commission and the Church Committee never even called those who were targeted by COINTELPRO and Key Sectors to testify before their so-called public hearings.

If censorship laws – disguised as access laws – are designed to protect the nation state from having to reckon with the human impact of its warfare at home and abroad, then we the people must resist by building our own collective archives and collective memory: recording the teachings of elders, collecting documentary materials from survivors, and organizing open platforms for political education and collective action – much like the Black Panther Party demanded in point five of its 10-point program.