One dreary night in March 2022, I stayed late at the shelter where I worked. My co-worker Julianne* sat across from me, typing on her ancient work laptop. “I think the draft is finished,” Julianne told me. The printer wheezed out a copy of the 11-page document, an application for a P-38.

P-38 is the form used by individuals – professionals or otherwise – to petition a judge to mandate an individual for psychiatric evaluation. Once completed, the petitioner must present a case before a judge clearly demonstrating a pattern of behaviours that indicate a decline in mental health and the ability to care for one’s self.

The form was for Edith, a frequent resident of the shelter who had cycled through housing and homelessness for many years. Recently, the city had evicted her from her subsidized apartment. In the month before Julianne and I completed the P-38, we learned that Edith had trouble getting her antipsychotic medication refilled. We had also witnessed her experience several interactions and conflicts with other residents that left her extremely vulnerable.

In the preceding two weeks, the shelter staff had made many attempts to liaise Edith with mental health care. Some of these interactions were intended merely to fulfill their roles according to the standard practices of professionalized service provision; others were attempts to avoid any type of mandated mental health care. The outreach nurses, front-line workers, and doctors all had attempted to speak openly with Edith about her changing behaviours, expressed concerns for her well-being, and offered her mental health support. The newly formed mobile crisis team, ÉMMIS (Équipe mobile de médiation en intervention sociale), wrung their hands after attempting to have a concrete conversation with her. Edith had no family, no known friends, or even solid community ties. As concerns for Edith’s safety mounted, Julianne presented the P-38 before a judge the next morning.

Rasmussen’s writing succinctly defines that abolitionist social work “simultaneously [works] to dismantle structures of harm and death” as it affirms life through new structures and “[transforms] people’s material conditions.”

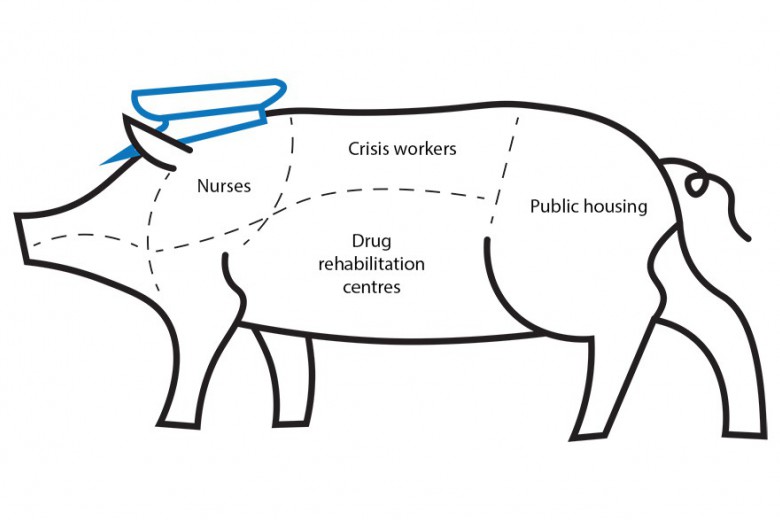

I returned to this situation while reading the recently published Abolish Social Work (As We Know It), a collection of essays that challenges professional approaches to social work. Abolish Social Work problematizes the current state of the field, particularly as it exists in the socio-political landscape following George Floyd’s murder at the hands of the Minneapolis police and the widespread call for police abolition led by the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020. The P-38 form is an example of what one of the book’s editors, Edward Hon-Sing Wong, describes as “the constellation of coercive apparatuses that involve the direct collaboration between mental health workers and the police.” In the instances that P-38 forms are granted, it is often police who provide transportation for individuals to the hospital for their evaluation, which further implicates social and mental health services within the carceral system.

Abolish Social Work reads less like an academic social work text than it does an anthology of creative community projects that exist in response to social needs. Although the book primarily features writers from Tkaronto (Toronto) and other urban areas across so-called Canada, the scope of the projects represented and the subject of the essays is diverse, ranging from issues around the carceral rhetoric of the popular anti-trafficking movement to the injustices Black women face in the health-care system. Many of the contributors to Abolish Social Work are Black and/or Indigenous, and they explicitly write about their own communities and the harms traditional social work structures have caused. Notably, the book also features the voices of those who have survived aspects of the social work system, such as the article written by Juvie about their own experiences as a Black survivor of Winnipeg’s child welfare system.

Abolish Social Work is divided into two sections. The first provides theoretical backing, explaining why the current approach to professionalization in social work is not tenable. The second provides concrete examples of social and care work that have been undertaken outside of what are considered the normal confines of professional social work. In preparing this article, I spoke with two of the book’s editors: Edward Hon-Sing Wong and Craig Fortier, as well as three contributors: Suzanne Narain, Krystle Skeete, and Heather Bergen.

The first essay in the book, by Cameron Rasmussen, outlines the “liberatory possibilities of social work,” crediting abolitionist thinkers and activists, particularly women of colour and Indigenous folks, who have paved the way. During our conversation, the volume’s editors were also quick to point out the individuals and communities from which they have learned these terms, practices and theories, specifically uplifting their comrades Mimi Kim, Durrell M. Washington, and Rasmussen who edited the related anthology Abolition and Social Work. “None of this is possible without context, and our book is meant to be read in dialogue with other texts,” explains Fortier.

“When we first got into the sector, it was about having people […] who just work with people. There’s just been a shift toward having licensed practitioners.”

Rasmussen’s writing succinctly defines that abolitionist social work “simultaneously [works] to dismantle structures of harm and death” as it affirms life through new structures and “[transforms] people’s material conditions.” Abolish Social Work upholds a realistic perspective: namely that social services can provide resources to keep people alive. To abolish social work tomorrow could result in increased structural abandonment of extremely vulnerable individuals. Rather, the book is, as Fortier and Hon-Sing Wong write, “rais[ing] serious questions about the viability of professional social work.”

Inside/outside perspectives

Questioning the viability of professional social work begs the question: is there still reason to even bother training folks in social work or social services? Krystle Skeete, who has been “working in the social sector” for about 20 years, states about her and Heather Bergen’s work: “We both got into the sector because of our hearts […] I don’t feel like a degree has defined that for us.” Skeete observed that even during their 20-year career, there has been a concrete shift toward increasing professionalization. “When we first got into the sector, it was about having people […] who just work with people. There’s just been a shift toward having licensed practitioners.” Bergen jumps off this point stating, “[we] have both been doing ‘social working’ for a really long time but neither of us have our Bachelor of Social Work or our Master of Social Work. This is work that’s really close to our hearts but it’s not something we are accredited in […] so that gives us both an inside/outside perspective on social work.”

Inside/outside perspectives can create both creative and challenging work dynamics due to different types of approaches and theoretical grounding. As Brianna Olson Pitawanakwat, a founder of Toronto Indigenous Harm Reduction, writes in her chapter, “shelter hotels […] were a revolving door due to harsh guidelines and often had no capacity to [support] the trauma that our [Indigenous] people live with.” Having worked in a “shelter hotel” specifically designed for urban Indigenous populations, I witnessed many instances in which a lack of formal training, or being on the “outside perspective” of social work, did not inherently make someone less inclined to rely on or collaborate with the carceral system.

Fortier, who works as an associate professor in the department of social development studies at the University of Waterloo, says, “there's a value in collectively training each other to respond to certain situations and instances [… social work] has a technical aspect." Fortier describes how working in a program not accredited by the Canadian Association for Social Work Education allows them the ability to push the boundaries of what a social work education might entail. Fortier also highlighted the intersection between social work and social justice movements, remarking, “there are some benefits in having people trained in therapy and social work, being in movements and being able to deal with conflict […] to name and address it, and understand what's going on."

Slow growth

The unaddressed challenge with abolitionist social work practice seems to be that of timing. The examples provided throughout the book are excellent and inspiring; they also seemingly rely on processes that build slowly. As Suzanne Narain states about the foundation of mutual aid and food justice project Black Creek Community Farm (BCCF), “a lot of time and consideration was put into [our] process […] there was no quick solution.” BCCF, along with many other examples highlighted throughout the book, seem to “move at the speed of trust,” as emergent strategist adrienne maree brown calls it, borrowing a phrase from Mervyn Marcano and Stephen Covey. Most contemporary social service organizations do not move “at the speed of trust” – not with workers, and not with service users. Crushed by unsustainable workloads, shockingly high demands for services and severe funding deficits, many front-line services simply lack the time, or rather, lack their leadership’s prioritization of trust building. In its desire to be understood as professionally legitimate, social work has deeply ingrained itself in the pacing of colonial white supremacy and late-stage capitalism.

One shelter I worked at so deeply ingrained its workers into a crisis-response mentality that it resisted closing even for weekly staff meetings.

The Baby Bundle Project, which provides wraparound support to Indigenous families giving birth in Toronto, challenges this idea. As Krysta Williams writes in her chapter, “there is an overfocus on meeting basic needs, which dehumanizes the dreams and goals ‘service users’ have for themselves, their children and their families.” This notion radically challenges the ways that front-line social work defends its legitimacy and its claims to urgency.

Front-line services are reactionary. The work culture of front-line services can often take on the same crisis-oriented and survivalist mentality of folks accessing services, which creates a real resistance toward addressing larger philosophical questions about values, morals, and actual approaches to practice. One shelter I worked at so deeply ingrained its workers into a crisis-response mentality that it resisted closing even for weekly staff meetings. Urgency mentality not only creates a ripe environment for worker burnout, but also perpetuates a dangerous experience for service users because there is not enough space or time to focus on building trusting relationships. Skeete describes the opposite approach used in the community building arts and advocacy group Freedom Fridayz. “It was just grounded in so much community and creating that space […] it became that space of healing, that space to grieve, that space to share.” Both in conversation and in her section of the book, Skeete highlighted this emphasis on spaciousness which stands in stark contrast to more traditional front-line service providers.

Heather Bergen, as a member of Community Action for Families (CAF) which provides support to those interacting with the family policing system, such as provincial child welfare agencies, described how CAF had to intentionally build in space to define their values. “Organizing around really deep, urgent trauma is very difficult […] it is really tough organizing [and] because that work is so intense for everybody, we were able to create a group culture where it was acknowledged and fine that we would step in and out of involvement with the group,” Bergen says. She also explained that, although not detailed in the book, CAF spent over a year simply outlining their mission and defining their values, one of which was to be “explicitly abolitionist.” The pacing of CAF disrupts virtually all my experiences of working in more formalized social services.

Abolitionist practice

In “The Only Good Social Worker is a Criminal Social Worker,” Chanelle Gallant offers useful, concrete ways for how social workers may subvert power structures and redistribute resources to those facing the most structural barriers. Gallant commands readers to self-reflect, asking, “How do we live out social work abolitionism today? But even trickier, how do social workers live an abolitionist life today?” Gallant begs individual social workers to begin to interrogate their own practice and to “avoid enforcing racist and fatal rules that are devastating to communities, like anti-drug laws.” Or, as the editorial team writes in the introduction: “Kill the Cop Inside Us.”

Co-workers – of many different identities and backgrounds – have told me that I am, at best, undermining their practice and, at worst, putting them in danger and failing to understand the risk they feel for their safety.

One of the great struggles of abolitionist movements is determining how to move theory into action, especially actions that can be scalable and practised by a wide variety of individuals in different circumstances. Many of the most specific examples advised in Abolish Social Work are aimed at an individual level.

As a front-line social worker, I’ve tried to enact some individual approaches to abolitionism – refusing to bar service users, refusing to call the police, and doctoring documentation so that individuals can access as much necessary material support as needed. At each juncture, these attempts have created intense conflict within my workplace. Co-workers – of many different identities and backgrounds – have told me that I am, at best, undermining their practice and, at worst, putting them in danger and failing to understand the risk they feel for their safety.

On a deep level, abolitionist theory critiques not just how to avoid reinforcing the carceral system, but also how to reconsider conflict and power dynamics within social groups and spaces. While it makes sense that Abolish Social Work makes little mention of how these groups are handling conflict within themselves, it would be useful to see further writing on how to open conversations about abolition in work environments that may be hostile to the very idea. Transforming the landscape of social work practice will incite conflict and it's useful to consider in advance how we might engage with this conflict.

The process of abolition isn’t supposed to be easy and there’s no way to publish a straightforward, step-by-step guide to social work abolition. I do believe, however, that forthcoming, complementary work would do well to deeply explore these issues of conflict and to provide case studies of spaces that have reoriented toward abolitionism in real time.

In writing this piece and inviting in my own implication as a front-line social worker, it is tempting to edit out my experience in perpetuating carceral social work practices, such as registering a P-38 like the one that petitioned Edith for psychiatric evaluation. But it is much more honest to state that I do not yet have the answers as to how to engage with social work abolition. As Hon-Sing Wong says, “not to romanticize it – none of this is perfect […] there’s that wariness too, of not contributing to a race [to] innocence.” That is to say, practising resistance within the normative confines of social work is not absolution.

Ultimately, the judge did grant the P-38 and Edith did receive urgent mental health treatment at the hospital. For a little while, she seemed to be doing better. But since these “legitimate” types of social work fail to change social context, and focus on individual situations, Edith’s health did not stabilize long-term. Her experience, like those of many others with whom I have worked, represents an indictment of the current complicit state of professionalized social work.

In the introduction of Abolish Social Work, the editors write, “Stop Teaching the Same Things.” Here, I would add: “and Stop Doing The Same Things.” Ideas and practices around social work abolition – and abolition in social work – not only invite a new sense of knowing, but demand a change in the way care is provided in real time.

*Julianne and Edith are pseudonyms to protect the privacy of both.