Ning Yang

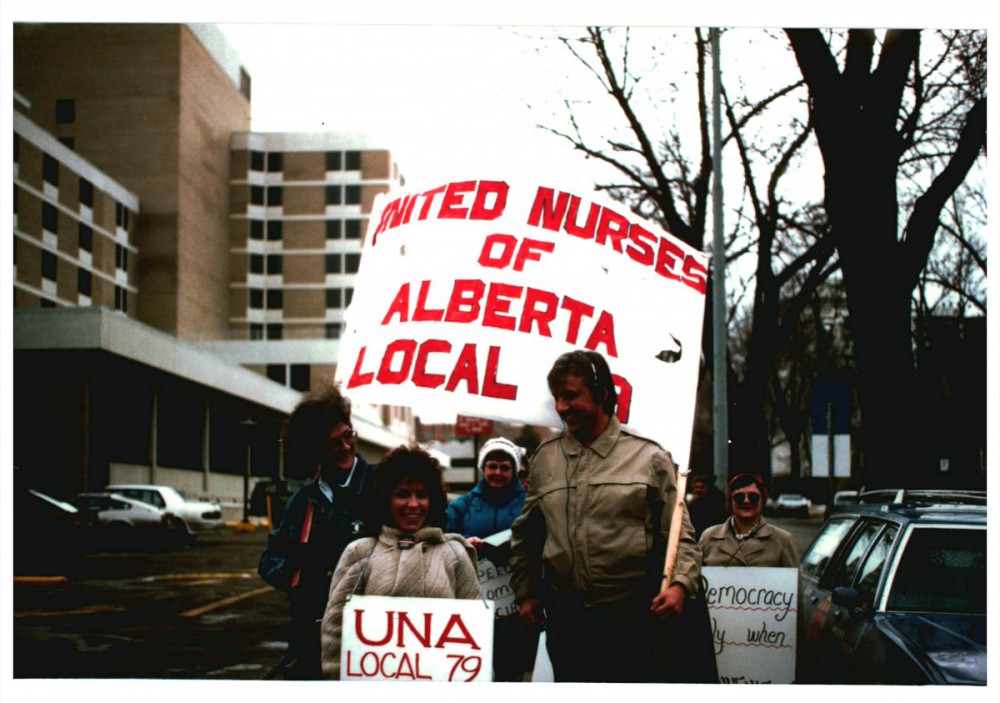

On a frigid snowless morning in January 1988, more than 14,000 nurses lined Alberta’s streets as clocks struck 7:30 a.m. United Nurses of Alberta (UNA) had declared an illegal strike. The strike made national and international news, prompting workers and unions from as far as a McDonald’s in California to donate.

It was risky to take job action – the government had imposed an outright strike ban on hospital workers after their last strike in 1982. Fed up with the government’s assault on their right to strike and proposals to decrease their wages, nurses were ready for a fight.

United Nurses of Alberta (UNA) on the picket line in 1988. Photos courtesy of UNA.

The Alberta government didn’t take the violation of the strike ban lightly. The union faced fines totaling $426,750, criminal and civil contempt charges were laid against more than 75 individual nurses, and many striking nurses were terminated from their positions. After a gruelling 19 days on the picket line, Alberta nurses successfully stopped the provincial government from clawing back their wages.

Today, nursing is again in crisis. Governments are understaffing hospitals, turning permanent positions into casual ones, and selling nursing jobs to staffing agencies. In 2018, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Canada was expecting a nursing shortage of 117,600 nurses by 2030. As a result, nurses today face increased workloads and physical and emotional exhaustion. In the past five years, vacancies in nursing have more than tripled. This has resulted in record-long wait times for patients, patients being turned away because of a lack of capacity to care for them, and nurses who are burnt out and fear that they are unable to provide quality patient care.

Given these conditions, it’s no surprise nurses are leaving the profession. Prior to the pandemic, 60 per cent of nurses planned to leave their current roles within a year, one quarter reported planning on leaving nursing entirely in search of greener pastures, and 24 per cent of nurses in Canada plan to exit the profession within three years, according to a 2021 survey. After more than a year and a half into the pandemic, in November and December 2021, 94 per cent of nurses were suffering from symptoms of burnout, with 45 per cent experiencing severe burnout, according to a Canadian Federation of Nurses member survey. More than half of surveyed nurses shared that they were considering leaving their job in the next year.

I’m a nurse and researcher based in Hamilton, Ontario, where I have worked on the front lines in both hospital and primary care settings. I’ve seen the quality of patient care worsen and nurses’ workloads balloon as the Ford government cuts away at the health-care system. I became active in my union, the Ontario Nurses’ Association, to push for better working conditions and increase the quality of health care we’re able to provide to patients.

This isn’t the first time austerity-minded governments have come for nurses’ working conditions and patient care to save a buck. To organize against pandemic-era health-care austerity, we can learn from nurses’ labour history.

When essential workers strike

Let’s look at what it means for nurses to be essential workers and how that impacts our ability to organize and take job action. In the 1920s, nurses pushed for professionalization. This earned them the ability to self-govern, establish professional training and credentialing, and ensure legal protection of the title “nurse” to be used only by individuals meeting specific criteria.

This professional identity means nurses must abide by certain professional standards. This includes maintaining essential services and limiting the scope of strike action for nurses whose day-to-day duties are considered essential. For example, the College of Nurses of Ontario’s practice guidelines state that if nurses withdraw their labour from essential service areas, they will be committing patient abandonment. Theoretical penalties include mandated training and education, temporary suspensions and fines, and nurses losing their licence to practise.

In Canada, the legal ability for essential staff to strike is provincially regulated. Some provinces, like Ontario, Alberta, and Prince Edward Island, have permanent strike bans for all nurses who perform essential work. These provinces’ governments replaced the right to strike with interest arbitration, where a third-party decision maker reviews both parties’ requests and declares a final and binding settlement. Defying these strike prohibitions comes with a threat of hefty penalties for individuals (including fines and imprisonment) and their unions (such as withholding dues payments from unions or even revoking the union’s right to represent workers entirely).

Patients spend hours or even days in the emergency room waiting for a hospital bed, and many patients aren’t getting the care they desperately need. Providing quality patient care feels impossible with the limited resources available to us as nurses.

Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia do not impose restrictions on nurses striking once their collective bargaining agreements have expired. In 2007, however, the Saskatchewan government attempted to legislate a strike ban for essential workers. In a victory for labour, this decision was struck down by the Supreme Court of Canada for violating workers’ rights and freedoms.

For the rest of Canadian provinces, governments have imposed restrictions against health-care worker strikes without declaring complete prohibitions. In some cases, like Quebec, these regulations are so strict they functionally constitute a strike ban.

These strike bans aren’t the only obstacle making it difficult for nurses to fight their provincial governments over unfair working and patient care conditions. Even in the face of a crumbling health-care system, many nurses are hesitant to take job action because they face the moral and ethical dilemma of balancing their duty to care for patients with the right to safe, secure, and fairly compensated work. Many nurses enter the profession because they want to provide quality health care to their patients. Are patients harmed during nursing labour action? Even during illegal strikes of the past, nurses have continued to provide necessary essential services. Still, leaving non-urgent care on standby for days, weeks, or even months is a tough choice to justify.

On the other hand, my colleagues are burning out left and right. Patients spend hours or even days in the emergency room waiting for a hospital bed, and many patients aren’t getting the care they desperately need. Providing quality patient care feels impossible with the limited resources available to us as nurses.

Lessons from nursing strike history

The fines and charges the Alberta government levied against striking nurses in 1988 seem incredibly steep, but provincial governments throughout history have chosen similar tactics. Despite their provinces’ strike bans, and amid threats of criminal charges and fines, nurses took to the streets on various occasions to protect the health-care system from austerity budgets.

Just over a decade later, in April 1999, 8,400 Saskatchewan nurses struck for similar reasons as their UNA counterparts in response to a nursing shortage causing understaffing, cancelled vacations, lengthy overtime hours, and compromised patient care and safety.

On the same day as the strike began, the provincial government passed Bill 23, ordering nurses back to work and making their job action illegal. Rosalee Longmoore, president of the Saskatchewan Union of Nurses at the time, told reporters, “Premier Romanow should consider that he may be able to pass laws forcing nurses back to work, but he can’t force nurses to stay in nursing. The actions of the Premier and SAHO [the Saskatchewan Association of Health Organizations] will make recruitment of nurses to Saskatchewan impossible. Imagine the effect this intimidation will have on the nursing shortage!”

Going on strike is the most effective way for nurses to fight back against their government’s attempts to sacrifice health-care workers and patient care to save pennies on their budgets.

Four months later, on the other side of the country, nurses in Quebec called for a wildcat strike on June 26, 1999. After being without a contract for 16 months and receiving an offer of only meagre wage increases, 47,500 members of the Fédération des infirmières et infirmiers du Québec (FIIQ) walked off the job. Using a similar tactic to the Saskatchewan government’s, Quebec passed back-to-work legislation on July 2, 1999, but the strike continued.

Chantal Boivin, the associate secretary at the FIIQ, reflects: “For more than a year, there was real guerrilla locally: overtime ban, right of refusal, days of recuperation, illegal work stoppage, not to mention all the spontaneous actions that were organized in many centres.”

Doctors joined picket lines in support of nurses, and supporters donated to help the union pay the hefty multimillion dollar fines levied by the government. The strike wreaked havoc on hospitals, postponing 16,200 surgeries. Despite disruptions to care, nurses had the support of the public, with 72 per cent in support of the nurses’ demands.

Today, nurses have the right to strike in Nova Scotia. But in 2001, the government legislated a strike ban, infuriating nurses across the province. To protest the ban (and get around it), the Nova Scotia Nurses’ Union and the Nova Scotia Government Employees Union tried a new tactic – threatening mass resignations. Over 1,450 out of the 2,100 nurses at Nova Scotia’s biggest hospital signed letters outlining their intent to resign. As researcher Larry Haiven remembers, “the nurses’ union had this series of ads which did a lot of damage to the government.” The ads, he says, in combination with the threat of mass resignation, broke the back of the government and resulted in major gains for Nova Scotia’s nurses.

In the past five years, vacancies in nursing have more than tripled. This has resulted in record-long wait times for patients, patients being turned away because of a lack of capacity to care for them, and nurses who are burnt out and fear that they are unable to provide quality patient care.

More recently, in 2020, the Alberta government threatened to outsource 11,000 public-sector jobs in hospitals to private firms, including in-patient food and lab services, laundry, and custodial services. In response, over 800 nursing care staff, custodial and maintenance staff, porters, licensed practical nurses, and health-care aides went on a wildcat strike.

Guy Smith, president of the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees (AUPE) which represented the strikers, told the Calgary Herald that “there was no other option but to fight to protect Albertans at risk.”

The strike resulted in 157 postponed non-emergency surgeries and plans to redeploy management to front-line care. Alberta Health Services (AHS) responded by threatening to discipline staff participating in, promoting, or encouraging the strike. The Alberta Labour Relations Board ordered striking AUPE members back to work the next day. Eight licensed practical nurses were reported by the AHS to their provincial regulatory body.

In Quebec, employers can address staffing shortages by instructing nurses to work legally mandated overtime (MOT). On the weekend of October 16 and 17, 2021, fed-up nurses refused their overtime.

“Who would like to be cared for by a healthcare professional who is working her third MOT of 16 hours in conditions that don’t even respect professional standards?” Patrick Guay, then vice-president of labour relations at the Fédération interprofessionnelle de la santé du Québec, asks. “It’s dangerous for everyone: the patients and our members!”

Organizing against pandemic-era austerity

Alberta nurses in 1988 prevented government clawbacks. Saskatchewan nurses won wage increases over six times what they were first offered. Quebec nurses won higher salaries and pensions, better job security, and parental rights.

These victories weren’t served to nurses on a silver platter. Nurses risked their livelihoods and marched on picket lines despite fines and threats of arrests and jail time.

That being said, not all militant action produced substantial gains at the bargaining table right away. “Unions have to play the long game,” notes Haiven. Even though Alberta nurses were unable to make major wage gains after striking in 1988, “the big victory came in the next round of collective bargaining, behind closed doors, outside of public attention. The nurses’ union got a big settlement in Alberta not in 1988, but I think in ’91 and I remember thinking, ‘ah-ha!’”

Low nurse-to-patient ratios, livable wages, and vacation and sick time to reduce burnout are all as much patient care issues as they are workers’ issues.

Nurses are the last line of defence between austerity-minded governments and patient welfare. Nurses who withdraw their labour recognize that going on strike is the most effective way to fight back against their government’s attempts to sacrifice health-care workers and patient care to save pennies on their budgets.

As working conditions and patient care worsen and the cost of living rises, Canadian nurses stare down the daunting task of bargaining in the post-pandemic economic climate. Whether we look back to lessons learned from and gains made by the wildcats of the past or embrace the “modern militancy” of nurses under no-strike mandates, we are entering a new and incredibly important chapter in Canadian health care labour – and workers have an opportunity to claim the single largest say in the future of nursing work. If any profession is up to the challenge, it’s nurses. There are 450,000 of us across Canada, and we’re highly organized – 90 per cent of nurses in Canada are unionized.

Some of the largest gains nurses have made in the face of austerity-focused governments have been through illegal striking. Nurses of the past have demonstrated that strike-prohibitive legislation, criminal charges, fines, and threatened revocation of professional licences will not stand in the way of fighting for their rights and better patient care. Low nurse-to-patient ratios, livable wages to improve retention and decrease staff turnover, and vacation and sick time to reduce burnout are all as much patient care issues as they are workers’ issues. And they’re issues worth striking over.