“If I were a young woman, I wouldn’t be alone with him.”

My 50-something-year-old male boss casually shared this advice with me on my first day of work at a large national union. He was giving me an overview of the union’s board of directors and said this as he pointed at the official portrait of one of the vice-presidents. I suspect he sincerely thought he was helping me. But the message I received was clear: misogynist violence occurs in this workplace, and women workers are responsible for protecting themselves from it.

I wanted to ask my new boss: “What do you think about the fact that this man is a danger to women in the workplace? What are you planning on doing about it?” But I simply nodded because it was the first day of my year-long probation and I was afraid to jeopardize the permanent, well-paid position that I had long thought was going to be my dream job.

The questions that continue to haunt me are: how many others are experiencing this? Why is it still happening? And what can we do about it?

Since 2007, I have worked at three different unions and been a member of five; this was not my first nor would it be my last experience of sexist and other oppressive attitudes and behaviour in the labour movement. The questions that continue to haunt me are: how many others are experiencing this? Why is it still happening? And what can we do about it?

To find answers to these questions, I spoke to 10 cisgender women and one trans person, all of them union members or staff in Canada or the United States. They describe a variety of ways that sexism permeates their unions and offer insights into the systemic and institutional reasons that sexism and other oppressive systems are still so deeply entrenched within labour. They also share ideas on how to fight back.

Heartbreak and betrayal

From workplaces, local executives, bargaining teams, and picket lines to city-wide labour councils and union conventions, the trade unionists I spoke with expressed a sense of betrayal by the labour movement, something I could easily relate to.

Since joining her local executive in 2018, Annette Bouzi, 42, who in 2020 became the first Black woman president elected to the Ontario Public Service Employees Union (OPSEU) local at Algonquin College, has been deluged with sexist and racist harassment so violent and severe that she filed both an internal union complaint and a complaint at the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario. The harassment ranged from violent remarks such as “let her drown” and excluding her from meetings and email communications to denying her a key to the local office and installing a camera in the local office to surveil her. Bouzi notes that her story “is sensational because of certain details like the camera, the surveillance, which are linked to notions of Black criminality,” but that her experience is only one among those of many women and Black people who experience oppressive behaviour within OPSEU.

While she was not surprised to encounter sexism and racism in her union because, she says, “I deal with it every day, living in this body […] what I did not anticipate, perhaps naively,” she adds, “was the intensity of the sexism and racism […] and the fact that this was condoned by the institution and the union. All these problems are not supposed to happen in a union.”

Bouzi notes that her story “is sensational because of certain details like the camera, the surveillance, which are linked to notions of Black criminality,” but that her experience is only one among those of many women and Black people who experience oppressive behaviour within OPSEU.

As president of the Winnipeg Labour Council (WLC) from 2017 to 2019, Basia Sokal, 37, faced extremely misogynist treatment by her union “brothers” and chose to step down before the end of her term. “I felt so heartbroken,” she says, “because I’m still working-class and I’ve always been involved in my unions. And I felt like I can’t participate [in the WLC] any longer because I don’t know who to trust. Even the fact that […] there were women holding up this bullshit felt just so sickening to me.”

Sokal describes sexist attitudes as open and commonplace in the WLC. “I really saw that in a lot of the conversations that came on the floor,” she says. “You know, being told things like ‘nice tits,’ ‘nice ass,’ and […] photo-ops with the typical […] white men leadership and, ‘oh we got to get a woman in here, it’s going to look really bad.’”

Sokal had her resignation speech recorded “to make sure that what I said was documented and there was no way to spin it,” she says. In her speech, she reads the first 18 entries of a six-page list of variously condescending, sexist, and threatening comments she had endured. These include: “We’ve been doing this longer than you’ve been alive,” “I used to think you could work with us, but you’re just nuts,” and “Why don’t you just quit?” Before reading the list, she reminded those present that “these were all said by brothers. Brothers in the movement, brothers in labour.”

At a Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) local, Anna, 30, describes a culture in which cisgender women and trans people carry the mundane, day-to-day work of the local while cis men often describe women leaders as “difficult” and erase cis women and trans people’s ideas and contributions by taking credit for them. (Anna asked to use a pseudonym out of fear of losing her job if she spoke publicly about her experiences of sexism.) Gizem Çakmak, 34, also a CUPE member, describes “a lot of stubbornness [on her part] and a lot of heartbreak” in her past nine years of activism within a Toronto CUPE local.

“I felt so heartbroken,” she says, “because I’m still working-class and I’ve always been involved in my unions. And I felt like I can’t participate [in the WLC] any longer because I don’t know who to trust."

Jess Turner, 37, an herbalist and educator living in Lenapehoking (New York City), worked as a researcher in three different unions in Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and New York City before leaving the labour movement in 2009. She left behind a “chauvinistic, patriarchal work culture,” an environment in which, “as a Black woman, [she] was both demeaned and perceived as a threat.”

Turner, like Bouzi, speaks of being a Black woman under surveillance in union spaces. She describes several experiences of co-workers reporting to superiors behind her back about things like challenges she faced in a project or having turned off her work phone late at night. On another occasion, she approached a staff union representative for support on a workplace issue she was facing and the rep reported her complaint directly to management without her knowledge or consent. (Staff who work at unions are often unionized themselves. Their unions are typically referred to as “staff unions.”)

“It was this feeling of, everything I do is under a microscope,” Turner says. “It’s a completely different set of working standards, where it’s like, I have to do everything perfectly. And I have to exceed the performance of everyone around me without additional compensation or acknowledgement. And the moment that I raise a flag about anything, I’m the one who’s the problem.”

Ultimately, she says, “it knocked me down. I fell into a really deep depression. […] This movement that I had believed in, you know, my dad joined the union when I was in high school. My family’s financial situation totally changed. […] In my first year of undergrad, I read The Jungle and The Communist Manifesto and The Wretched of the Earth and I was like, ‘Oh my god … the capitalist overlords.’ And that was the energy that I came into those jobs with, and to have the experiences that I did was just pretty soul-crushing.”

Labour’s roots in patriarchal white supremacy

The trade unionists I spoke to readily identified the patriarchal and white supremacist history of the labour movement as the source of its oppressive culture and structures. The story of organized labour in North America is the story of craft unions – which represented workers such as printers, tailors, stonecutters, and carpenters – refusing to admit “unskilled” immigrant workers into their ranks in the early 20th century. It’s the story of male negotiators speaking on behalf of the young women matchstick manufacturers at the E.B. Eddy company in Hull, Quebec, who were barred from sitting at the bargaining table across from their employer. It’s the story of unions like the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees (CBRE), whose constitution explicitly stated that membership was only open to white people.

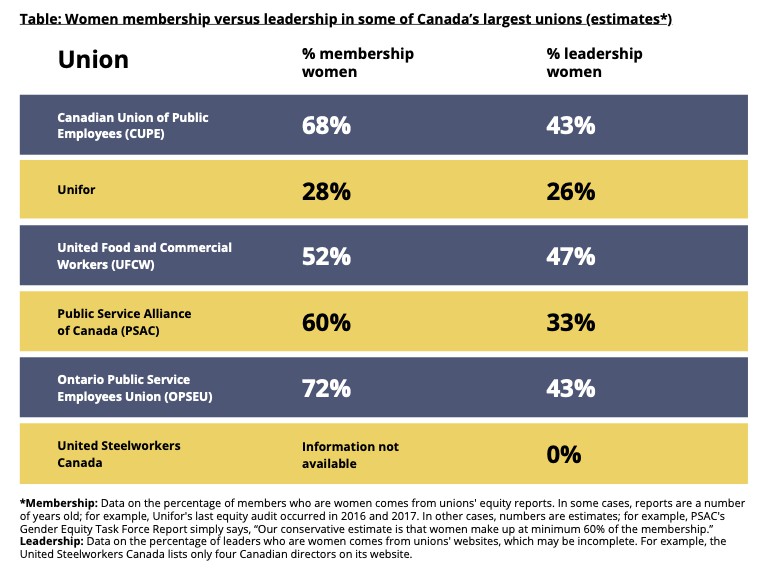

I knew this history and I knew from personal experience that today, union leadership bodies are typically dominated and run by men. Looking more closely at the current leadership of unions in Canada, however, even more clearly demonstrates their connection to their patriarchal white supremacist origins. While many of Canada’s largest unions have a majority female membership, almost none have a leadership team that reflects the union’s number of women members.

The limited data on racialized and Indigenous representation in these unions paints an even starker picture of the power imbalance – both in the data’s absence and, where it exists, in the small number of Indigenous and/or racialized workers who hold any major decision-making power. It is worth noting that at Unifor, one of Canada’s largest private-sector unions, the only Black woman in a leadership role is the first racialized workers representative at the union. At CUPE, one of Canada’s largest public-sector unions, the Black and Indigenous women leaders are, respectively, the diversity vice-president – racialized workers and the diversity vice president – Indigenous workers.

Beyond the clear reflection of white supremacy in union leadership, the attitudes and behaviours that the women and trans trade unionists describe as permeating their unions, including power hoarding, fear of open conflict, defensiveness, and paternalism, are among the hallmarks of white supremacy in organizations.

“It’s about power,” Bouzi says. “It’s held by white men. When you have a place where the majority are white men, and these white men are the ones making structural decisions, the organization becomes inherently racist and sexist.” Bouzi describes the closed, patriarchal culture within her local, where members are “not supposed to run for positions on their local executive unless someone taps them,” she says. “With a local all run by white men, only other white men would be tapped for leadership roles.”

"Hetero-patriarchy is powerful and does not want to self-reflect,” she says. “The people in positions of power in the union movement have a vested interest in the status quo.”

If women are permitted inside the decision-making structures, men often still seek to maintain control. While men at the WLC actively recruited her to run for the role of president, Sokal says that they did not want to cede any real power once she was elected. “I was constantly told that, you know, we’ve been around for a lot longer than you. We know what we’re doing,” she recalls. Sokal says she was told that “you girls are just put in these positions to […] make unions look progressive.”

“I felt that every single day, that I was basically tapped on the shoulder to run because it will look really great to have a woman,” she explains.

Many also named the union environment itself as a serious obstacle to accountability. Turner describes a “level of self-righteousness, that white men […] but even men of colour, that they kind of convinced themselves that they are above reproach. […] It’s an unwillingness to share and collaborate and be uncomfortable. Hetero-patriarchy is powerful and does not want to self-reflect,” she says. “The people in positions of power in the union movement have a vested interest in the status quo.”

Fighting systemic patriarchal white supremacy in unions

While the story of the labour movement in North America is a story of exclusion, it’s also a story of resistance. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) held meetings in 16 different languages in order to meet the needs of the same immigrant workers rejected by the craft unions. The women matchstick workers at E.B. Eddy created the first union of women workers in Quebec and went on strike against literally toxic working conditions and the male supervisors who sexually harassed them. Black railway workers formed their own union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, to fight for their dignity as workers and as Black people. Carrying on this spirit of resistance, the trade unionists I spoke to offered many strategies for fighting sexism, racism, and oppression in labour, which are outlined in the following subsections.

Implementing existing accountability mechanisms

Bouzi says that OPSEU possesses policies to hold members accountable in cases of serious misconduct, “but the rules don’t apply to the white men in charge. They can behave however they want and the union will not impose serious consequences.”

She points to the OPSEU leadership’s unanimous vote in September 2020 to suspend the union membership of seven members involved in a raid of OPSEU corrections workers by the Quebec union Confédération des syndicats nationaux (CSN). Raiding, or organizing members to defect from their union to join a different one, is one of the most serious offences in labour. These members, who were also removed from any elected or appointed positions, can request reinstatement of their membership after a period of two years.

“Clearly, the union has the power to impose harsh penalties for behaviours it deems inappropriate,” says Bouzi. “Sexism and racism are not [among] these behaviours.” In cases of sexist and racist harm, she says the union claims that “the employer is the one who has to make people behave properly. The union is powerless.”

“Clearly, the union has the power to impose harsh penalties for behaviours it deems inappropriate,” says Bouzi. “Sexism and racism are not [among] these behaviours.”

The perpetrator of the violent misogynoir in Bouzi’s local was directed to take training on anti-Black racism, sexism, and patriarchy. OPSEU’s executive board suspended his “member in good standing” status and removed him from his union office only when he refused to do the training, which he then completed and afterwards regained his former status and union role. However, Bouzi says it is unclear what, if anything, he learned. In August 2021, she had still received no apology from the perpetrator.

Sokal also believes that unions must enforce more serious consequences when leaders engage in oppressive behaviour. “The right thing is to step down,” she says. “We see that happen with politicians, we see that happen in corporations. […] And I’m sorry, that’s called accountability. It’s nothing personal, but at the bare minimum, you are accountable for the organization that you are leading, and if you want to see change, you start with being the change.”

Using transformative justice approaches to addressing harm

Many trade unionists emphasized that the union complaint process exacerbates the trauma that a person has already experienced. “Survivors of racism and sexism have not only lived the violence, which is in itself traumatic,” explains Bouzi, “but through a complaint-based process, we often have to relive the violence by providing copious details of not only the trauma, but its impact,” she says. On top of this, she continues, “there is also the huge performance of anti-oppressive work that is hard to witness. The corporate statements make bold promises that never materialize into tangible action that equity-seeking people can feel.”

“What needs to be done,” says Bouzi, “is to centre the people who experience the harm,” which gives them the opportunity to shape what the accountability process would look like. She also feels strongly that “unions need to make the space safe immediately and stop those perpetrators of sexist and racist behaviours from attending the same meetings and contacting survivors.”

"The corporate statements make bold promises that never materialize into tangible action that equity-seeking people can feel.”

Anna also proposes that unions change their approach to responding to harm. She explains that “our society is really invested in the idea of good guys and bad guys” and believes that unions should adopt the prison abolitionist ethos that “no one is disposable and there are no monsters.” In the same spirit, Çakmak presents CUPE Local 3903’s Internal Sexual Violence Policy as an example of a transformative justice approach, noting that she continues to push for similar policies at the provincial and national levels of CUPE. Passed in 2019, the policy states that “meaningful justice processes that work towards healing, engaging the people who have caused harm, and repairing relationships can be developed. It is a process that seeks individual justice while recognizing that we need to transform our communities to address the root causes of violence.”

Addressing harm quickly and directly among peers

Sokal, who has returned to her job as a letter carrier, describes a culture in her Canada Post workplace in Winnipeg where accountability takes the form of ongoing conversations among peers. If a co-worker has said something oppressive, when “we sort our mail in the morning, somebody will come up to you and say ‘Hey, that’s not cool.’ And you know [if] you do it again, you’re getting called out in front of all of your co-workers,” she says.

“This is what Labour Council should have been like,” she continues, “and this is what every union should be like. Where we talk about things, you know, and discuss things. And I’m really lucky because […] while we are all different, we are able to educate each other in a very respectful way.”

Seeing and embracing the whole worker

A common thread in many of the strategies that the trade unionists proposed is the belief that unions should value the fact that they exist within multifaceted communities and embrace an intersectional approach. Not only is this more just and inclusive, but it is possible that it will make unions, a sector in decline since the onset of neoliberal attacks in the early 1980s, more relevant and more powerful. Outlining the approach of “whole worker organizing” in her book No Shortcuts, union organizer Jane McAlevey suggests that “when the workers systematically bring their own preexisting community networks into their workplace fights, workers still win, and their wins produce a transformational change in consciousness” of their power as workers.

The stories of the trade unionists I interviewed often made me despair. But I gained renewed optimism from their strength, wisdom, and conviction that, as Bouzi maintains, “unions are for everyone,” including racialized women, Indigenous women, trans and non-binary people, and white women like myself. “Change has always come in reaction to people organizing for it and fighting for it,” Bouzi reminds us.

"It’s nothing personal, but at the bare minimum, you are accountable for the organization that you are leading, and if you want to see change, you start with being the change.”

Those I interviewed also emphasized the possibilities of workplaces and unions as both transformative and transformable spaces.

While she is no longer unionized, Turner is committed to “creating as many sparks as possible” in her workplaces. “There’s a lot that needs to shift, and I have faith,” she says. “At my last job, I took on a role of organizing people to not just take whatever was handed to us […] and to build consciousness of the fact that work is [a] politicized space.”

“No fight is easy,” says Çakmak. “I come from a unionist family in Turkey so […] you don’t just let it go. You fight back.”

Anna, who now works as a union staffer, recalls the advice that a union comrade gave her after she expressed frustration about a sexist incident, saying, “I don’t know why I’m so angry, I’m used to this.” The woman turned to her and said simply: “Do not ever get used to it.”